Trump vs. British Accents

/Last week, British Members of Parliament gathered to debate whether Donald Trump should be banned from entry into the United Kingdom. This was in response to an online petition signed by over 500,000 Britons who demanded this action following the front-running Republican presidential candidate’s controversial proposal to temporarily ban Muslims from entering the United States should he win the presidency.

The petition was well clear of the 100,000 signatures needed to require Parliament to debate the issue, for it is possible for the Home Secretary to ban individuals deemed to be “fostering extremism or hatred” or may “constitute a threat to public policy or public security.”

The debate lasted for three hours, and I watched some of it with some amusement. It really wasn’t a debate so much as it was a session for running the gamut of insults (including the word “wazzock”) against the outspoken New Yorker and condemning his public statements. Partly for this reason, many people questioned whether this was the best use of three hours on the taxpayers’ dime (or in this case, ten pence), considering especially that few MP’s actually advocated to ban him from the country.

However, the proceedings were a unique opportunity to see the diversity of the United Kingdom on display.

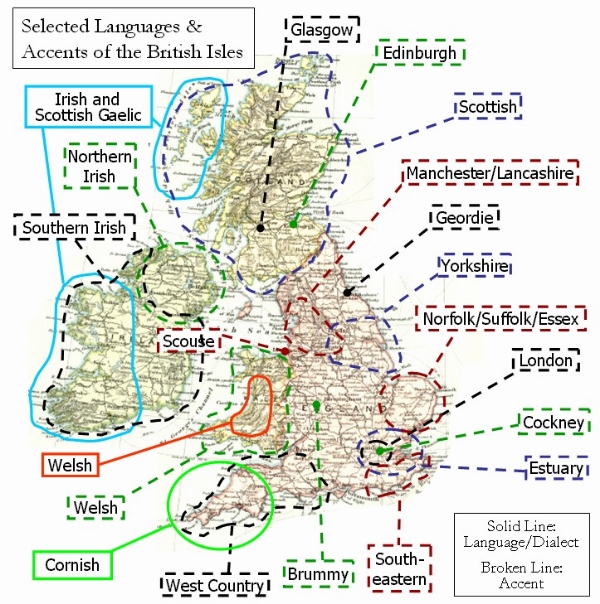

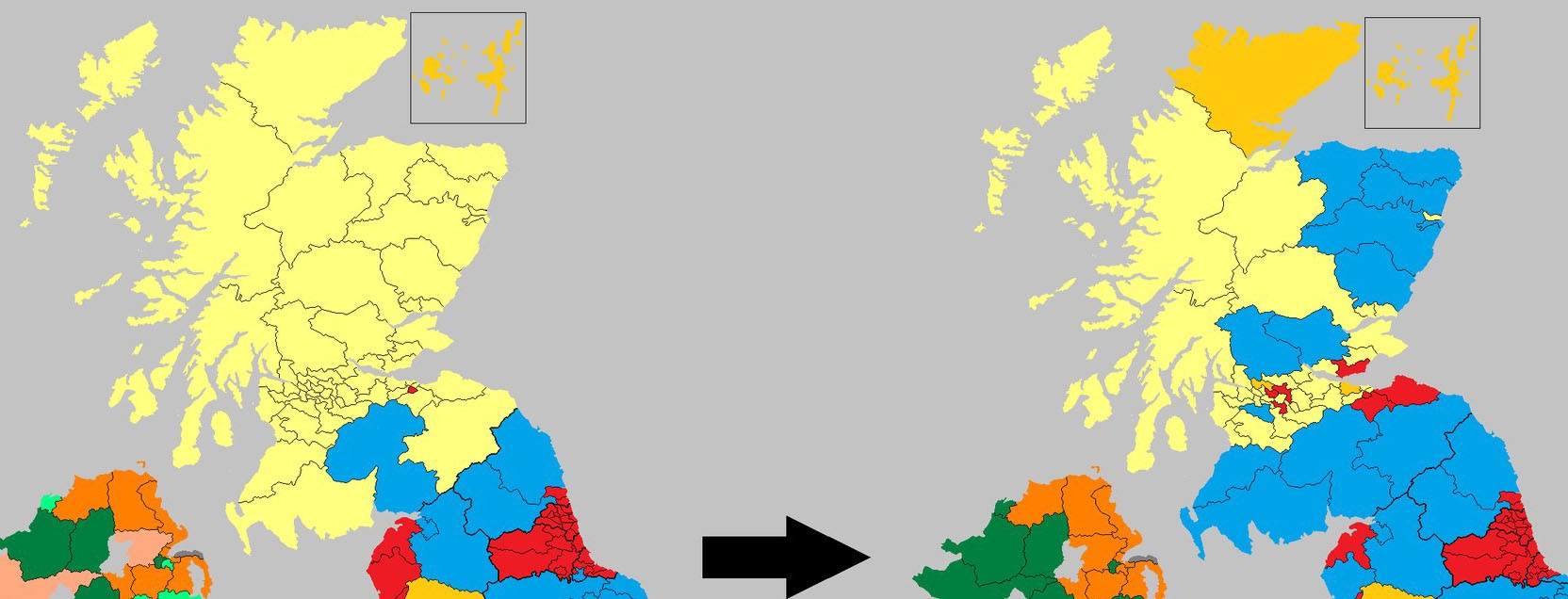

There is no one British accent (just as there is no one American accent), and indeed, the panoply of accents and dialects throughout the UK is quite staggering and in my opinion, is one of the things that make the United Kingdom such a unique and fascinating. The “debate” last Monday featured probably but only a sampling of those accents as the members to stood up to speak.

Not (yet) being an expert on British accents and dialects, I could only guess at what I was hearing, but I felt as though I did generally hear Welsh accents, along with some that could be identified as coming from the Midlands. Specifically, there may have been one MP with a Brummie accent and another carrying the sounds of Lincolnshire. Going south, the Cockney and Estuary accents from London and the Southeast made prominent appearances, but so did some Scottish accents – including Glaswegian and others hailing from West Central and the Lothians. Some of these could have been mixed with other accents into what may have been the Scouser accent of Liverpool or mistaken for other accents of northern England, such as Geordie and those generally from Yorkshire, Cumbria, and Lancashire. From across the Irish Sea, a Northern Irish lilt was also prominently featured – probably Belfast or Ulster-Scot, which bore much in relation to the aforementioned Scottish sounds. Back on the mainland, the West Country/Cornish voices were also probably represented during these three hours of anti-Trump.

In the end, no action was taken against the man who now stands a good chance of winning the Republican nomination for the presidency of the United States. The consensus seemed to be that "The Donald" made disreputable statements about many groups and individuals, but that a ban went overboard for man they saw as acting foolishly and stupidly, and this was summed up by one MP who said that Trump’s actions amounted to “buffoonery”, and that this should be met “not with a ban, but with the great British response of ridicule.”

If nothing else, it was – at least for me as a Britophile – like traveling through the United Kingdom at warp speed, with the country showing its diversity and dynamism via the complex and colorful fabric of its voices, as seen here in this video compiled by the Washington Post which features the National Anthem.

If only they could "sing with heart and voice" more often on issues of greater importance facing the country. Here's the hoping they will. Until then, keep up the accents.