In the National Interest

/After the past two weeks here in the US, there may be a conclusion with regard to the election of a new Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Ohio Republican Representative John Boehner has been at the post (which among other things, is second in line to the presidency) since 2011, when his party took control of the lower chamber of Congress, but announced his resignation last month. In his place was supposed to Kevin McCarthy of California, who is the current Majority Leader in the House. However, he was beset with criticism over his relative inexperience as a Member of Congress, as well as for his public gaffe’s, which include the apparent revelation that the Republican-led committee investigating the 2012 terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya may have been a vehicle for attempting to damage then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who is currently seeking the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.

Current Speaker of the House, John Boehner of Ohio. Gage Skidmore via Flickr cc

But the biggest issue he faced was the potential opposition from about 40 hard-right backbenchers, who (despite political reality) do not want to makes compromises with the Democrats in the Senate (where Republicans have a majority, but not have enough members to overcome a potential Democratic filibuster) or with President Barack Obama, who wields the veto pen (and will not, for example, sign a bill that will overturn his signature health care law).

Even so, McCarthy had every expectation to get enough votes from his fellow Republicans to nominate him as Speaker behind closed doors before a vote before the full House with the Democrats, where the Republican majority should have ensured him the speakership. But at the last minute, he withdrew his candidacy to the shock of virtually everyone in the Washington Beltway and the wider political world. In doing so, he threw what was supposed to be a more-or-less pre-arraigned process into total disarray as John Boehner announced that the election would be postponed indefinitely.

Since then, the party has been looking again for a person to ascend to the role which Boehner wishes to vacate. The problem is that no one (especially people with White House ambitions) really wants the job because they know that it will likely be their political graveyard.

Congressman Kevin McCarthy of California, the House Majority Leader. U.S. Government and Printing Office (Public Domain)

Indeed, part of the reason why Boehner wants out is because much of his time as Speaker has been characterized by dealing with the divisions within his own party. Even though the Republicans have had a majority in the House since 2011, Boehner has had a tough time ensuring that he could get a majority of them to vote with him on contentious issues, such as raising the debt ceiling and passing a budget. A small but vocal minority of hard right conservatives (known as the House Freedom Caucus) have attempted to use showdowns on budgets and the debt ceiling to force the defunding of things to which they objected, such as "Obamacare" and Planned Parenthood.

Boehner knew that Senate Democrats (who had a majority until this year) would block such measures and even if they made it to the White House, the president would veto them. A long-time representative and establishment figure, he knew that compromises would have to be made, but would be forced to go to the brink by this minority of representatives – many of whom have been elected only within the last five years on a platform of opposing Obama. Eventually, Boehner would be able to push through his agenda, but only after high stakes drama and the threat of government shutdowns, and indeed, there was a costly shutdown in 2013.

This was why Boehner wants to leave, but with almost no one else amongst House Republicans wanting the speakership for the same reasons, this caused some outside-the-box thinking – literally, since there’s nothing in the Constitution which states that the Speaker must be a member of the House. Names of prominent Republicans who are no longer in public office had been mentioned, including former vice president Dick Cheney and Newt Gingrich of Georgia, who served as Speaker from 1995-1998 while a member of House.

The most intriguing possibility was the election of a compromise candidate between Democrats and Republicans who are tired of the obstruction by their fellow members (i.e., the tyranny of the minority). After all, the Speaker needs only support from a majority of the overall House, and need not come from the majority party, and indeed, a Speaker having broad support from throughout the House may have been the ideal that our Founding Fathers wanted.

Nevertheless, speakers elected along party lines has usually been the tradition, and anybody who broke this mold would have be taken an enormous risk.

However, it now appears that conventional thinking will prevail with the announcement that Congressman Paul Ryan will seek the nomination to become Speaker. The 45 year old representative from Wisconsin has been a member of the House since 1999, and ran for vice president as Mitt Romney’s running mate in 2012. Ryan is well-regarded throughout the party and seen as a unity or consensus candidate, which is why he was the most often-mentioned name for the job. But he – currently the chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee – expressed no interest in it.

But after coming under much pressure, Ryan has announced this week that he would become a candidate for becoming Speaker, but only on certain conditions (more on that later). Yet, even if he becomes Speaker on party lines, it may well lead to the end of his political career and any prospect of occupying the White House in the future due to the hard choices he will have to make which may make him deeply unpopular with the base voters of the Republican Party. If John Boehner ends up serving the remainder of his term as Speaker, he is looking at the possibility of calling on Democrats to help get around the rebel backbenchers and push legislation through.

Wisconsin Representative Paul Ryan - the reluctant Seeker for the Job . Gage Skidmore via Flickr CC

All of this has been presented as taking one for the team, or more appropriately, doing what’s best for the country.

This is nothing particularly new – the notion of a politician stepping up to do things in the national interest, and often in the face of opposition by his or her own party. John F. Kennedy wrote about this in his book, Profiles in Courage, and how some of his predecessors in the US Senate put themselves into great political and personal jeopardy by doing what they believed was best for the country.

In Britain, a politician who comes to mind in this regard is Ramsay MacDonald, a man who remains quite controversial in British politics.

MacDonald was born in Lossiemouth, Scotland and was a founder of the Labour Party. In 1924, he led a minority government as the first Labour prime minister of the United Kingdom (and the first from a working class background), but only lasted for less than 10 months. Five years later, Labour was elected back into power with MacDonald as prime minister for a second term with a larger mandate this time around, although he still led a minority government with support from the Liberal Party.

Two years later, MacDonald was faced with dealing with the economic crisis that had begun with the 1929 Stock Market Crash, and had blown into the Great Depression. As unemployment soared and government finances deteriorated, MacDonald’s government struggled as it attempted to reconcile two conflicting aims: balancing the budget to maintain the Gold Standard and prevent a run on the pound, as well as maintaining social welfare assistance to the poor and unemployed. A committee was appointed to review public finances, which in July 1931 recommended sweeping reductions in public spending (including welfare and unemployment payments) and public sector wage cuts to avoid a budget deficit. MacDonald and a majority of the Cabinet agreed with the need to balance the budget, but this was a slim majority, with the Cabinet effectively split down the middle and senior ministers – some of whom wanted to enact countercyclical fiscal policies advocated by John Maynard Keynes – threatening to resign from the government in protest.

Faced with this, MacDonald was prepared to tender his own resignation to King George V, but the King insisted that MacDonald should stay at his post and lead a National Government with Conservatives and Liberals. MacDonald knew that if he did this, he would draw fire from his party and bring odium to himself, but the King believed that – in this moment of crisis – that MacDonald was the only man who could be prime minister and make the decisions to get the country on track.

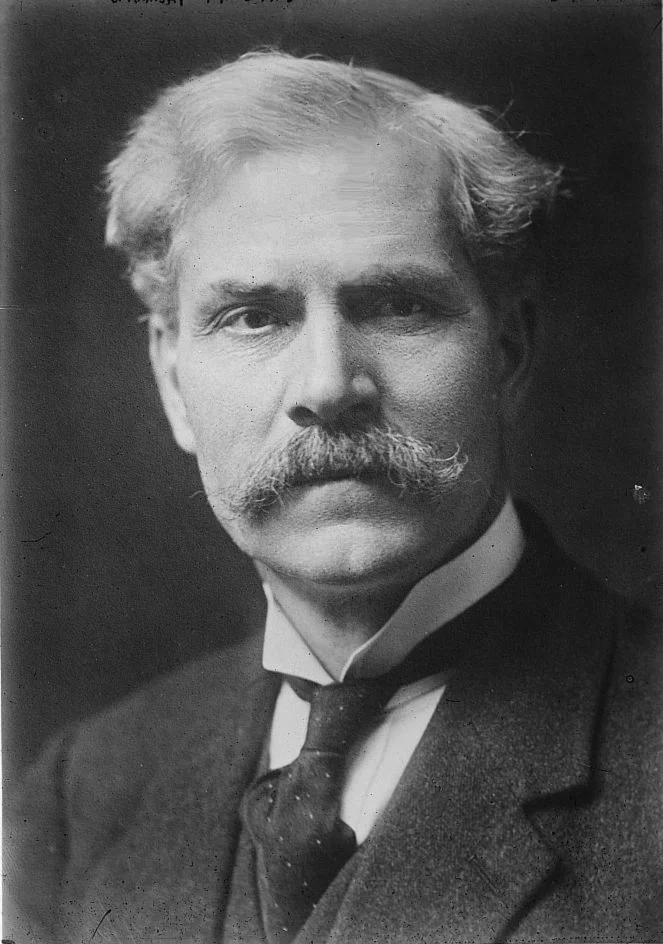

Ramsay MacDonald, Britain's first Labour Prime Minister. George Grantham Bain Collection - U.S. Library of Congress

MacDonald agreed to form a National Government, which meant bringing down his own Labour government, and by doing so, he and other Labour people who supported the National Government were expelled from the party that he had helped to create. In the ensuing general election that year, the National Government won 554 seats – one of the largest electoral mandates in British political history, and though MacDonald remained prime minister, he was only one of a handful of pro-coalition Labourites (under the name National Labour), and the government was dominated by the Conservatives. The main Labour Party itself suffered its worst defeat up to that time, and took over a decade to recover, which only stiffened the antipathy toward MacDonald, even though he still believed himself to be a Labour man and believed that the National Government would be temporary.

Under his watch, the government finances were righted with the reductions to public spending, and the economy eventually began to turn around. He resigned as prime minister in 1935 due to declining health, and died two years later at the age of 71, leaving a mixed legacy behind.

To some Labour Party members to this day, MacDonald is seen as a power-hungry traitor who made incestuous deals with the enemy – the Tories – to stay in Downing Street at the expense of his party and the people he was supposed to represent – the working classes. On the other hand, he is also viewed as a co-founder of that party who helped to carry it from being a protest organization to being a legitimate party of government, and who when on to make tough decisions in the national interest of the UK. In both veins, he can be considered courageous for doing what he believed was right.

More recently in our time, the decision of Nick Clegg and the Liberal Democrats to join a coalition government with David Cameron and the Conservatives following the hung parliament of the 2010 general election is arguably another example of a politician risking so much for himself and his party in the pursuit of doing what was thought best for the national interest. With the British economy still reeling from the effects of the financial crisis and Great Recession, compounded with the eurozone crisis and other international economic issues, it seemed only reasonable for them to join forces with Tories, who were the biggest party in the House of Commons, but just short of achieving an overall majority.

As with Ramsay MacDonald in 1931, Nick Clegg believed – or at least, made everyone else believe – that in a moment of crisis, a strong coalition government was needed to steer the UK, as opposed to a weak minority Tory government. One path offered stability and a path way to recovery, the other offered instability and an economic roller coaster, along with a potential second election that year. Financial markets and businesses, who prefer stability and certainty, would have questioned the ability of the British government to handle its affairs, especially if there were multiple elections and uncertainty of who would lead the country.

Nick Clegg's Decision to Join the Conservatives in a coalition government was controversial in 2010 and has Cost his party dearly. Chatham House via Flickr CC

As it was, the Nick Clegg took his party into coalition with the Tories, and to the surprise of most political observers, the coalition government – with Cameron has prime minister and Clegg as deputy prime minister – survived through the end of the five year parliament. However, the LibDems ended up paying a huge electoral price for being seen as propping up the Tories and acquiescing to their program of austerity, which included the raising of tuition fees (which the LibDems had promised they would abolish). They were credited in some circles for putting the brakes on (or watering down) some of the more controversial policy proposals from the Conservatives – such as overturning the Human Rights Act and weakening the fox hunting ban. In the end however, it did not really matter. They lost waves of seats in local council elections, the elections to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, the 2014 EU election, and in this year, the UK parliamentary election in which they were reduced from 57 seats to just eight.

Back home in the US, the saga over who becomes the next speaker may not lead to such consequences, but there’s the chance that it could, especially if the new Speaker is a Republican who uses Democratic votes to get legislation through, or – more unconventionally – the new Speaker is a compromise between both parties. One party or the other will accuse people within it of treachery and selling out for power and prestige.

However, this likely will not be happening since Paul Ryan relented under pressure to step up and offer himself as the Republican nominee for the speakership, albeit on the certain conditions – most significantly, that he must have House Republicans united around him if he is to be the consensus candidate for the job and if he is to be an effective Speaker. To this end, he made an appeal to acting in the national interest – saying the speakership was not a job he wanted or ever sought, but that he came to the conclusion that this was “a very dire moment”, not just for Congress or the Republican Party, but for the entire United States, for without effective leadership in the “People’s House”, the business of the nation cannot be done.

He made it clear that he is a principled conservative who will not acquiesce to the White House, but also made it clear that he wants to lead as the principle spokesperson and agenda setter for the House GOP without the threat of revolts from the hard right of the sort that have made John Boehner’s life a living hell for the better part of the last four years. For more assurances, Ryan has said that he will seek to make it more difficult to remove a sitting speaker, which is a procedure that requires only a simple majority vote. Some Republicans balked at these demands, but it appears that Ryan has pulled the great bulk of them together, including most members of the Freedom Caucus), and this has given him a clear pathway for the nomination and the speakership itself.

Whichever way it goes for the Republicans (and for that matter, politicians of any party in the US or UK), the common refrain is that so often, those who step up and make sacrifices – personally and politically – for the good of the country are often vilified and do not receive any thanks for it, except in the annals of political history, and usually long after such people step away from the political stage. They do what others either cannot or will not do due to the lack of political courage, and they know very well that it all may well come crashing down on them in the end. In a hyper-charged political era where we ask for more statesmanship from our politicians, perhaps it is time that such people were looked in a more measured light in their time, and ours.