Just Another "Westminster" Party

/Underneath the facade of being anti-Westminster, the SNP is just another "Westminster Party" (Credit: Jim Trodel via Flickr cc; Modified by Wesley Hutchins).

Throughout the independence campaign last year and the general election campaign this year, the SNP talked a lot about how it represented a “new form” of politics, and that this was diametrically different from that of the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats (a.k.a., the “Westminster parties”) – characterized by cronyism, use of public office for personal gain, and political favoritism.

Eventually, they and their acolytes went along to claim that this was not just an ethical difference between the politics of the SNP and the other parties, but a difference of moral and political cultures between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Scottish politics, we were told, was egalitarian-based, transparent, and emphasized doing right on behalf of the people. It was characterized by men and women who were honest, upstanding, trustworthy, and – most importantly – incorruptible. UK – or rather “Westminster” – politics was all about using the public trust to extract personal benefit, tightly-knit cliques, inherent corruption, and cronyism that made even saints and angels swear in disgust.

Not so with Scottish-based politics, so this was presented as yet another reason of how Scotland and the rest of the UK were so incompatibly different, and why therefore, Scotland should have voted to separate from the rest of the UK and break up the Union. (And if you voted No, you obviously supported - according to the more fanatical Yessers - pedophilia, illegal wars, and throwing sick people off of benefits).

In short, the politics of “Westminster” was the politics of sleaze and helping yourself, whilst the politics of Scotland (and especially the SNP) was the politics of cleanliness and helping others.

This was a message which chimed in well with a massively cynical public that was fed up with politics and the political establishment following – among other things – the parliamentary expenses scandal and the sense that politicians looked out for themselves and their close associates and family. The SNP successfully conflated this with Westminster as an institution – as if to say this was representative of the UK as a whole – and has massively benefited as a result.

But recent events have called this image into question.

First, is the issue of Michelle Thomson, MP for Edinburgh West, who came to prominence during the referendum as the managing director of the pro-independence group Business for Scotland, and then became the SNP’s candidate for the Edinburgh seat in the House of Commons, which she won in the general election last May.

She was glowingly touted within the party, not least because of her business background, which helped to give the party a pro-business image despite its increasingly left wing rhetoric to gain Labour voters. Indeed, she was portrayed – not least by herself – as the sort of business person who managed to combine commercial success with a sense of community and social justice. As such, she became the party’s Westminster spokesperson on Business, Innovation, and Skills, and was seen as a rising star.

However, it turns out that part of her more recent success came from her and her husband purchasing properties from desperate sellers at knock-down prices in the aftermath of the financial crisis and Great Recession – people who were almost certainly facing dispossession and needed properties taken off their hands in the face of economic hardship. In one case, the Thomson’s bought an apartment from a pensioner couple for £73,000, even though the market valuation according to the Land Register was £105,000. Another person sold his property to the Thomson’s for £60,000, even though it was valued for £25,000 above that amount.

Taking advantage of these below-market prices, the Thomson’s eventually built a property portfolio estimated to be around £2 million with 17 homes, which has probably grown in part because some properties were sold for massive profits which then went toward purchasing more expensive ones, and therefore increasing their personal wealth substantially.

The controversy surrounding this had its seeds in May 2014 when Christopher Hales, the solicitor (lawyer) for the Thomson’s, was struck off for professional misconduct by a disciplinary tribunal which concluded that he “must have been aware that there was the possibility he was facilitating mortgage fraud” in relation to the work he did for some of his clients, including the Thomson’s.

It finally came to light when the Sunday Times featured a report on the Hales affair and his links to Michelle Thomson, which has sparked a police investigation, the resignation of Thomson as an SNP frontbench spokesperson, and her suspension from the party, which means that the SNP has 55 MP’s at the moment (down from 56) as Thomson is now an Independent MP (in similar fashion to Labour’s Eric Joyce (Falkirk) during the 2010-2015 Parliament).

Now, some people may say that Thomson was not an MP at the time, and that this had nothing to do with official conduct, such as using public office for personal gain – either for yourself or for close friends and relatives.

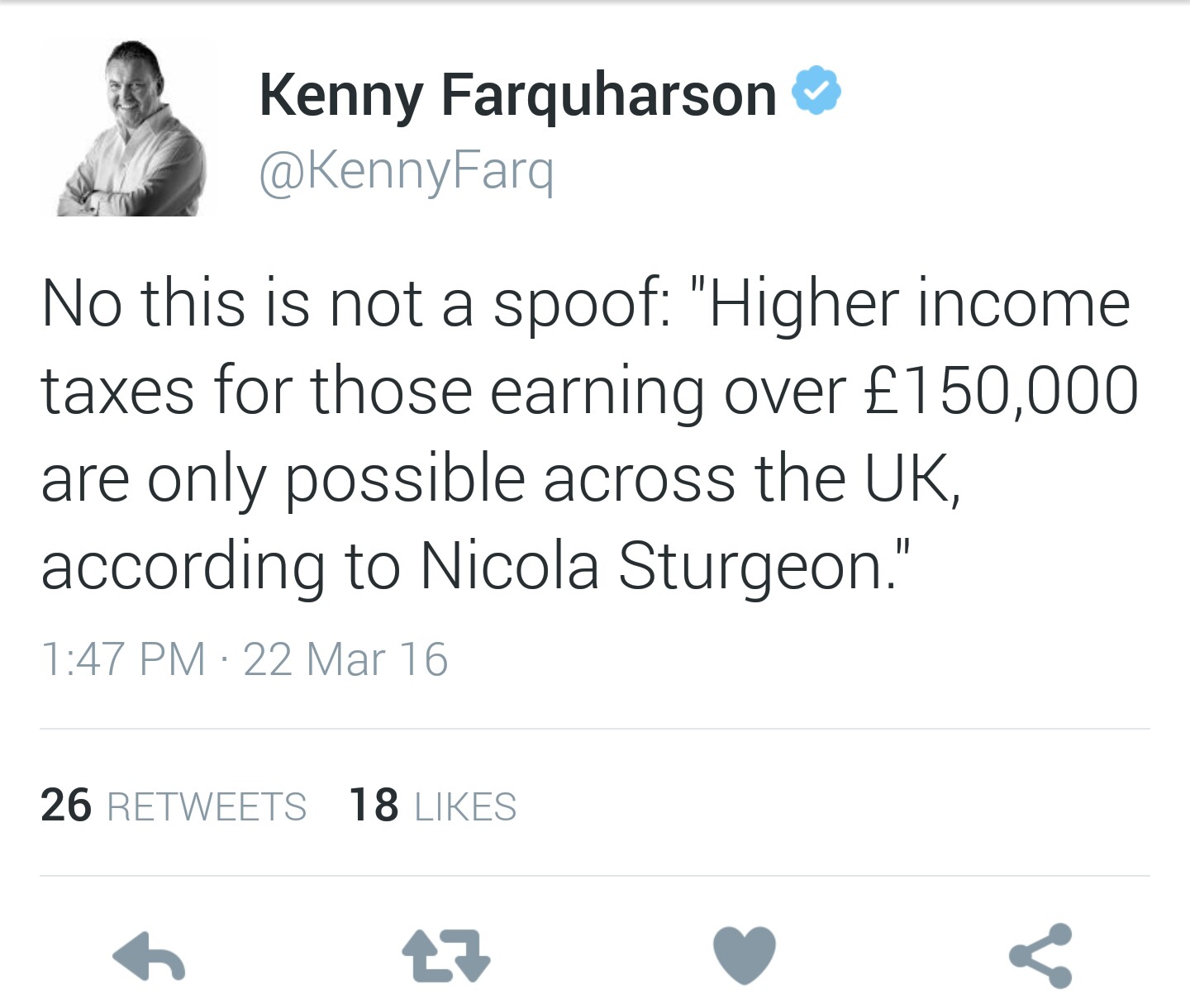

Fair enough, but then, what about the brouhaha surrounding the T in the Park music festival and the Scottish Government’s decision to spend £150,000 of public money on it? The reason – ostensibly, at least – from Culture Secretary Fiona Hyslop was that the money was needed because if it was not given, the festival may have moved out of Scotland, with a huge cost to the economy. But from all accounts, the festival was a profitable concern backed by private sponsors, so why the need for public spending here, when it could have been used to build houses or provide college places?

The answer may have to do with the fact that the concert promoters had obtained the lobbying services of Jennifer Dempsie, a former special advisor to former SNP leader and Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond, as well as the partner of Angus Roberston – the party’s leader in the Commons.

Now there is nothing to suggest that Dempsie or the concert promoters did anything wrong or illegal, or indeed, that T in the Park would not have received the funding from Holyrood if Dempsie was not lobbying in its behalf. However, it goes without saying that having Dempsie on board certainly did not hurt in the pursuit of the funding, and it may not be a stretch to think that her close connections to senior party leaders helped along to ensure funding for the festival.

In the same vein with regard to Michelle Thomson, there is nothing illegal about purchasing property at below market rates from people in a desperate situation – economic or otherwise. It must also be noted that at this point, Thomson has not been convicted of anything, much less formally accused or charged with a crime. Therefore, there is no need for her to resign her seat, and it will be for the proper authorities to decide if there is evidence that she had engaged in mortgage fraud, and if she is formally charged, it will be a court of law which decides her legal fate.

On this note, it is now known that Law Society of Scotland “informally” raised her now-disgraced former solicitor Hales’ case with the Crown Office, but only “officially” brought it up in July this year after Thomson had become an MP. This has brought about speculation that the delay may have been due partly to the fact that Law Society committee secretary responsible for disciplinary tribunals was a member of the pro-independence group Lawyers for Yes and an admirer of Michelle Thomson. On top of that, it has been confirmed that the head of investigations at the Law Society had received the tribunal report naming the Thomson’s and their business partner, and that the Crown Office had asked for detailed case files in December 2014 and in April this year – just before the general election – but only received them in July.

The Law Society has rushed to defend its staff from any accusation of impropriety, but the rushed press conference on Thursday appeared to raise more questions than answers – chief among them being, why did it take a year for the Crown Office to receive the case files from the tribunal investigation? At this point, there is no evidence that anyone from the Law Society acted improperly and sat on this case, so as not to endanger the independence campaign or the SNP’s – and especially Michelle Thomson’s – general election campaign. But the whiff of impropriety – that an investigation was stonewalled for political purposes – does not look good.

In the court of public opinion, it may already be too late for Michelle Thomson, for even in the case of Thomson as a non-public official at the time of her property dealings, it brings into to question her commitment to social justice and gives a bad image for a party that claims to be standing for ordinary people against predatory interests that seek to profit from their misery.

Between this and the T in the Park affair, you may cynically say these things happen without regard for politicians of any political party. Certainly, some Nationalists will say that “Westminster politicians” do this all the time. Nothing to see here; move along, citizen. (Furthermore, we have our own issues with cronyism in the States.)

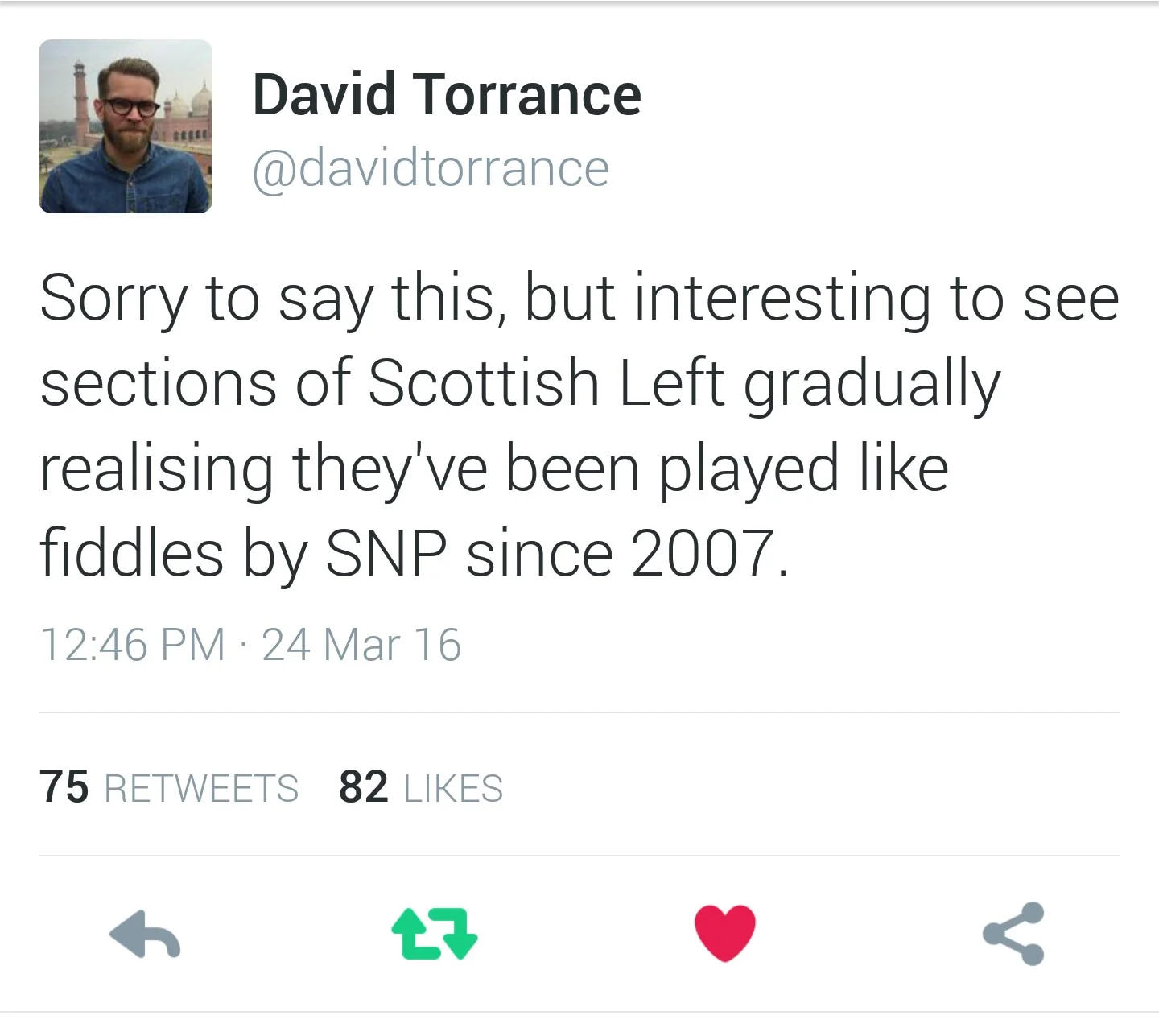

But, is that not the point? The SNP has gained traction by portraying itself as something unique and in another world from the “self-serving Westminster eite.” Without this distinction, what else does the SNP have going for it (aside from wanting to break up the UK)?

However, the reality is that the SNP has never really been Ms. Goody-Two-Shoes. It will play politics and play dirty when necessary. It is a ruthless and well-oiled political machine that is not above doing whatever is required to suit its political ends. By the end of last week, Sturgeon was effectively throwing Michelle Thomson under the bus for the fact that she is no longer – at least for now – an SNP member, and Jennifer Dempsie is no longer a Holyrood candidate. At the end of the day, the only thing that matters is The Cause.

As for First Minister Sturgeon, what do we make about her claims that she and others in the party had no clue about Thomson’s business dealings in the course of being vetted to stand for election to the Commons? In a party supposedly as disciplined as the SNP, one would think that some sort of thorough background investigation would have raised a few red flags.

Perhaps this can be excused by the fact that the party experienced a tremendous growth spurt following the referendum – climbing from around 30,000 members to over 100,000 in less than eight months, and making it the third largest political party in the UK. During that time, it may be believable that the SNP simply did not have enough staff at the time to handle all of their business from the referendum to the general election, and that they had little choice but to take Thomson at her word that there was nothing that could even remotely blacken her name and cause embarrassment for the party.

Nonetheless, serious embarrassment has been caused, not least because the words “mortgage fraud” has appeared alongside pictures of Sturgeon and Thomson together in newspapers, online articles, and other media. Similarly, the praise that she received from other senior SNP figures (during the referendum and leading up to the general election) has been plastered about to underscore just how much of a rising star she was, in part because of her business experience. For that matter, if they did not know what that business experience was, why did they take it at face value and make her the spokesperson for Business?

But if Sturgeon can claim deniability with regard to Thomson, how does she square away with the decision to sanction to public grant for T in the Park? Her chief of staff, Liz Lloyd, was aware of the request for taxpayer money and even offered advice on how agencies of the Scottish Government could assist in the funding. The Culture Secretary and member of Sturgeon’s cabinet, Fiona Hyslop, has come under fire for signing off on the grant without rigorously looking into the finances of the event, and it is now known that grant was not paid out until after the event had occurred.

Then, what about Sandy Adam, an independence supporter who had given almost £100,000 to the SNP and the Yes campaign over the last three years (as well as £5000 to Michelle Thomson for her campaign)? His property company had been given a Scottish Government loan of £1 million, and selected to take part in a lucrative scheme where mortgages for new houses are guaranteed by the government.

Perhaps this is a bit too harsh, because after all, we are all human and seek to use connections whenever possible to achieve personal ends, and this is not always illegal. Nor is it illegal to take advantage of certain opportunities when they arise.

This isn't to say that we ought not expect more of our politicians and other public servants, because of course, we should. However, we should not be fooled into believing that any political party has a monopoly on morality, for all of them have good apples as well bad ones. And, let's be honest: who wouldn't at least try to take advantage of the fact that they have friends in high places? That's been going on since time immemorial.

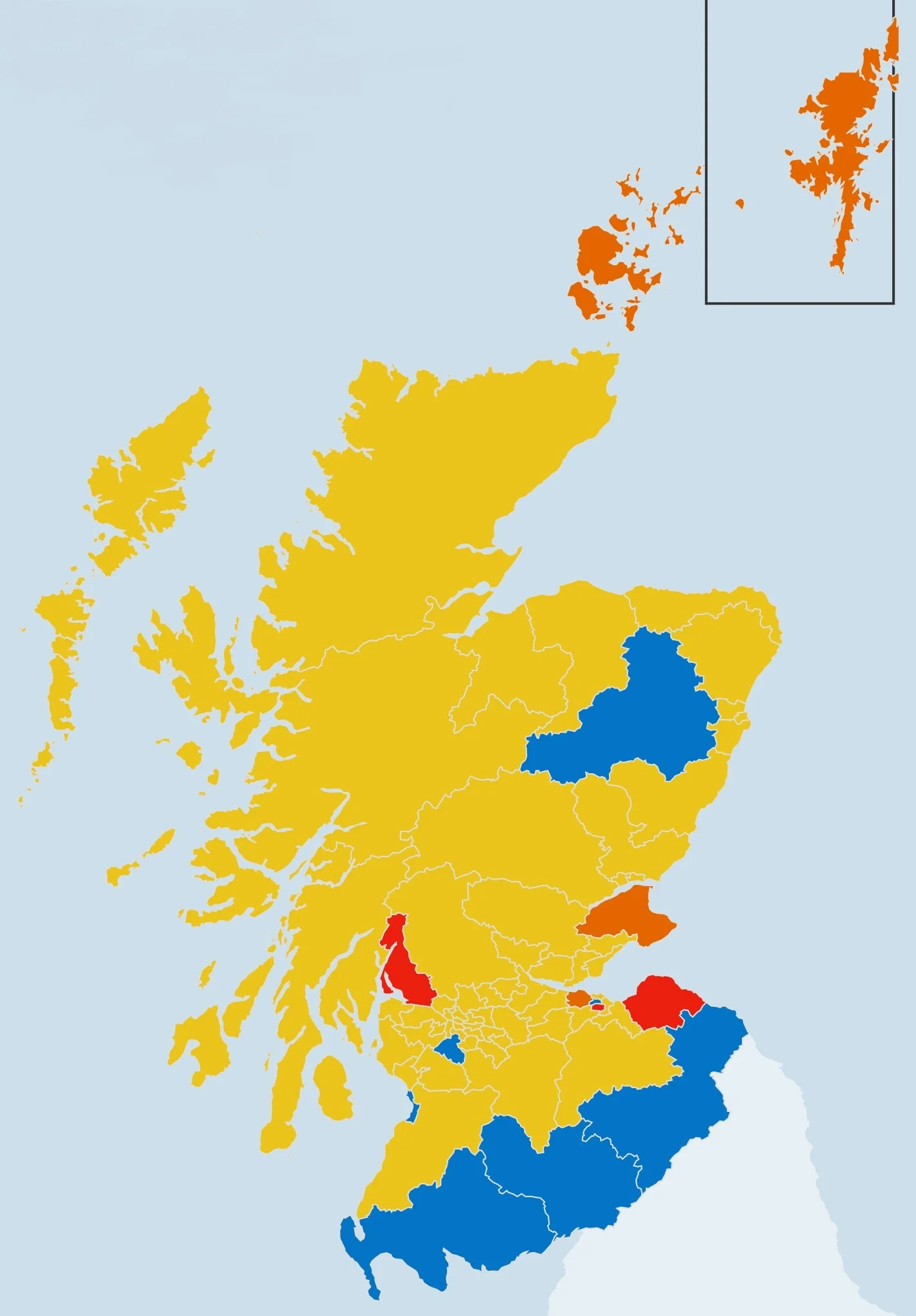

But again, we are talking about a political party that been quite sanctimonious in placing itself on a pedestal as a paragon of clean politics free of cronyism, dubious expense claims, breaching the public trust, and other characteristics of big bad “Westminster.” In the process, it won 56 Commons seats and almost won the referendum at least partly based on this message of them being the “good” politics that was only available in Scotland, and the other “Westminster parties” being the “bad” politics that was un-Scottish.

Now it seems that the SNP has a few things in its own house it must attend to, and that it has more than its fair share of cronyism and other behavior that many people find reprehensible in politics. This may not be enough to bring down the SNP overnight, but if the current issues continue to persist, and/or if more problems like Thomson or T in the Park arise, the party may well find itself in the same position as the “Westminster parties” it so routinely criticizes for just such behavior.

At the very least, it exposes their empty rhetoric and takes some of the shine off of their popular, carefully-crafted, focus group tested, and made-for-media image. The mask is beginning to slip.