Are Labour and the LibDems committed to the Union?

/Image Credit: The Laird of Oldham via Flickr cc

That’s the question being asked by supporters and opponents of both political parties after their leaders in Scotland – first Kezia Dugdale of Labour, and then Willie Rennie of the Liberal Democrats – announced that members and parliamentarians (MP’s, MSP’s, and MEP’s) were free to campaign for separation in the event of another independence referendum. Dugdale in particular stated that she wanted to “lead a party that is comfortable with people who voted Yes and No” in the last referendum (which was held last year) in which Labour fought for a No vote and Scotland’s place within the United Kingdom.

The party had participated in the Better Together campaign – the cross party effort to save the Union – which featured Labour campaigning alongside the Conservatives (Tories) and the Liberal Democrats, the two other mainstream pro-Union and UK-wide political parties, and when the referendum was held on September 18th, 2014, the No side won with 55% of the vote. This meant that the United Kingdom was kept together with Scotland affirming its part in the 300 year old Union.

However, this victory came with a heavy price.

Throughout the emotionally-charged campaign, the SNP under Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon had appealed to traditional Labour voters by portraying a Yes vote for independence as the only way to achieve a “fairer society” for Scotland. The alternative, they claimed, was continued “Tory governments which Scotland didn’t vote for” – a reference to the fact that while the Conservative-led coalition UK government (with the Liberal Democrats as junior partners) at the time had a majority of seats in the House of Commons throughout the UK as a whole, it only held a minority of seats in Scotland (one Tory and eleven LibDem), and therefore in the eyes of the SNP, had “no mandate” to govern Scotland (even though Scotland is part of the UK).

Labour was therefore portrayed as standing in the way of Scotland being “free” of Tory rule from the British Parliament at Westminster (where Scotland elects MP’s like the rest of the UK), and as such, it was also portrayed as part of the “Westminster Establishment”, where it along with Tories and LibDems were virtually indistinguishable from one another. Being part of Better Together only confirmed this image, which was played to the hilt by the SNP and other independence campaigners.

Even after they were defeated, the Nationalists saw a spike in popularity as the message about Labour being no different from the Tories resonated in places such as Glasgow and West Central Scotland, Lanarkshire, and Dundee, which had been voting Labour for generations, but now felt disillusioned and taken for granted by a party which had (supposedly) abandoned its traditional working class and left-wing values in pursuit of chasing swing votes in Middle England to win UK-wide general elections, and had been standing “should-to-shoulder” with the Tories during the referendum – leading to pejorative of “Red Tories.”

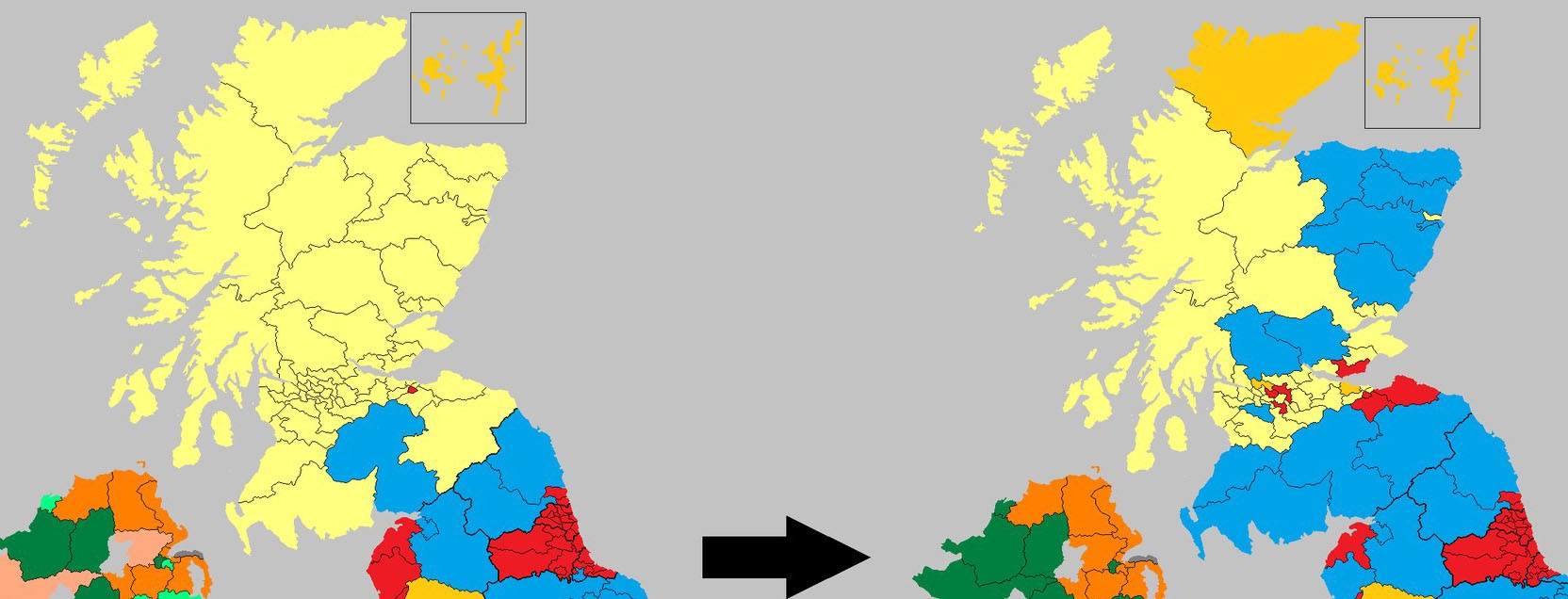

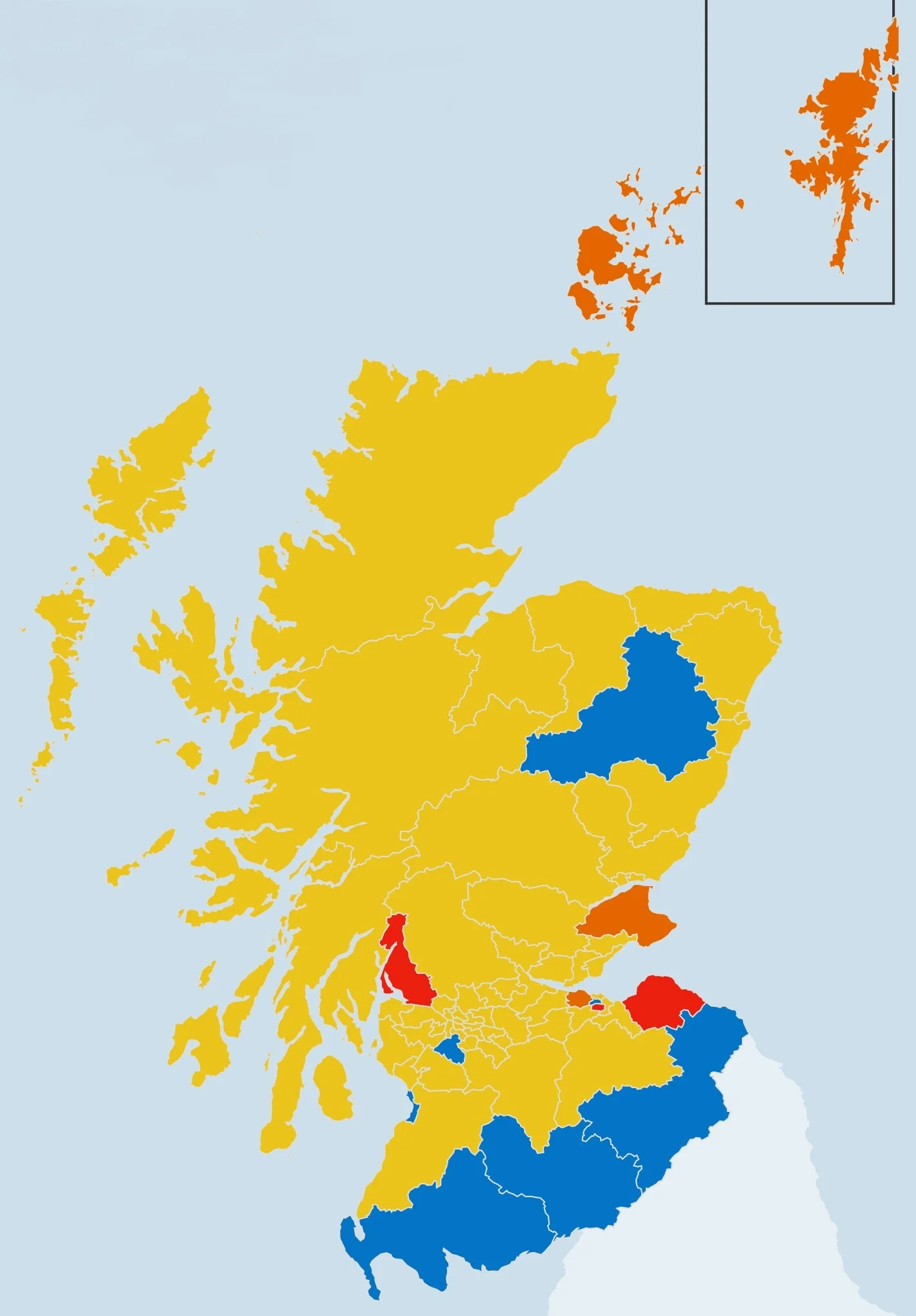

The result was that around a third of traditional Labour voters abandoned the party during the referendum, as well as during the general election in May of this year, where it lost 40 of its 41 Scottish seats to the insurgent SNP – ending the promising careers of Scottish Labour’s most talented politicians of this era, and contributing to Labour’s stinging defeat throughout the UK as a whole. Among those who lost his seat in May was Jim Murphy, whose resignation as leader of Scottish Labour ignited an election to replace him, which was won by his deputy Kezia Dugdale, who has been tasked with the awesome duty of recovering the party from its deep political nadir.

This has led to Dugdale extending an olive branch to the hundreds of thousands of Yes voters who either voted Labour in the past or would be otherwise inclined to vote Labour were it not for the SNP.

In response, Labour’s commitment to the Union has been brought into question, not least by many of its supporters who vigorously supported a No vote last year, and remain strongly supportive of Scotland being part of the UK. Members and supporters of the Scottish Conservatives (officially the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party) have taken the opportunity to promote themselves as the only party that can stand up to the SNP and truly support the maintenance of the Union, and party leader Ruth Davidson has claimed that she no longer knows what Labour’s position on the Union is anymore, but that her party will always argue for Scotland within the UK.

Indeed, on its face, it would appear that Labour is retreating on the Union by trying to invite the very people who rejected its stance on the constitutional question and the arguments it had put forward in support of that stance. After all, why would these people want to vote for a party that is pro-Union?

On the other hand, upon closer examination and thought, it appears that there is more to Dugdale’s positioning than meets the eye.

Indeed, I believe that Dugdale is trying to put the constitutional questions aside by saying that Labour need not be completely and entirely defined by being a pro-Union party, and instead should be known for what it wants to do to achieve better social and economic outcomes for people in areas such as health, justice, education, and policing, where the SNP are vulnerable after eight years in government, having won the elections to the devolved Scottish Parliament at Holyrood in 2007 (as a minority government) and in 2011 (as a majority government).

It was that record combined with the questionable economic basis for independence which helped Dr. Scott Arthur to make his decision to back the Union and a No vote through participation in Better Together. He later joined Scottish Labour and campaigned to help re-elect Ian Murray, who is now the only Labour MP from Scotand.

In response to CyberNats who deluged him with abuse for asking SNP leader and Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon on live television why her government voted against a living wage five times, Dr. Arthur wrote some commentary which eventually made its way to the pages of the Daily Record and his own personal blog. In it, he says that Labour must not fall into a trap whereby it can be portrayed as putting the Union before everything else, whilst it is the SNP whose own constitution outlines its first aim as “Independence for Scotland” and the “furtherance of all Scottish interests” in the secondary.

In contrast, it is Labour whose constitution outlines aims such as ensuring opportunity, publicly accountable (or owned) public services, and the deliverance of “people from the tyranny of poverty, prejudice and the abuse of power.” To this end, he further states:

“Labour must change Scotland’s political narrative by sticking to its values. It must promote itself as the party of social justice. The party which fights inequality and defends public services. Sure it wants Scotland to stay in the UK, but this is because remaining in the UK, even when we have a Tory government, is the best way to deliver social justice in the long-term.”

In addition:

“The arguments for Scotland staying in the UK are legion. They range from a shared history to a common culture and a collective love of a good curry. These arguments of the heart, and many others like them, have great resonance for many Scots. However, Scottish Labour’s argument must be about standing in solidarity with the rest of the UK. It must be about pooling and sharing resources – an easy argument when Scotland’s per capita deficit exceeds that of the rest of the UK.”

Furthermore, Dr. Arthur adds that in the SNP’s obsessive drive toward independence, it bangs on for more powers while almost refusing to acknowledge the powers it already has at its disposal at Holyrood, and less still, the new income tax and borrowing powers on the way via a Scotland Bill at Westminster – the contents of which were negotiated by the Smith Commission in which the SNP took part and signed off on (before continuing to complain that it wasn’t enough).

From this vantage point, the SNP only discusses the constitution and demands new powers as a means distract from what they can already do, with the long-term aim being to achieve independence gradually, regardless of if it actually makes Scots better off, or if it provides greater opportunities to those who need it.

In response, Dr. Arthur cites Sun Tzu and his seminal work, The Art of War, as the way forward for Scottish Labour, for the Chinese military strategist believed that the key to victory was the ability to choose the battlefield, and that for Labour, the battlefield it must dominate is social justice and in developing a narrative about how it will use Holyrood’s powers to achieve it.

In other words, being pro-Union won’t be enough for Labour to recover, not least because there are not enough No voters to go around for the three main parties. Yes, it is true that the No side won with 55% of the vote on nearly 85% turnout, but in terms of elections, this does not compare favorably with the fact that in the 2010 UK general election, the three pro-Union parties amassed 77.6% of the vote between them and held 53 of the 59 Scottish seats in the Commons. In this year’s general election (with a lesser turnout than the referendum), that share collapsed to around only half of the vote, and along the way, the SNP got 56 out of 59 seats.

Arguments over electoral reform and proportional representation aside (partly because some of us had no problem with the current system when the pro-Union parties were dominant), this is simple math and brute electoral reality, and Labour must win over people on ideas and policies that can improve the day-to-day lives of themselves, their families, and the greater society at large.

Remember, the SNP almost buried its nationalism to win at Holyrood in 2007 and 2011 on a platform of governmental competence (in contrast to the 1999-2007 Labour-LibDem administrations) and popular policies having nothing to do with independence, and this resulted in winning over people who at the time were not (and in some cases, still are not) minded toward independence. They got themselves into power by playing up having an alternative with regard to bread-and-butter issues that affect people’s lives on a daily basis, and because they knew that banging on about independence alone was not a vote-winner.

The old-school fundamentalists in the party did not like this out of concern that independence would be lost in the agenda, but the SNP under Alex Salmond, and now Nicola Sturgeon, has learned and played well the politics of gradualism and the long game. They convinced people to vote for them based on issues relating little to independence, and then worked toward cultivating such people towards supporting independence – a process that has taken place over weeks, months, and years – perhaps all the way to Referendum Day and beyond.

So far, this method has paid massive dividends to the SNP as a political party and for their cause of separation. They know that not all of their members and voters want independence, but that does not matter so long as they get the votes they need to win seats at Holyrood for a pro-independence majority and therefore claim a mandate for another referendum. At the same time, they will continue to make an appeal to people based on policies outwith independence and cultivate them towards agreeing with the SNP’s first and foremost aim.

The trick for Labour is for it to do the same thing in reverse to the SNP – challenging its record in government and offering a viable alternative that can get the support of those who voted Yes as well as No. Furthermore, just as there were some people who voted SNP, and only came around to supporting a Yes vote over time because they liked what the SNP was doing in government, perhaps the long-term strategy of Labour is to convince such people to see what it can do in government – both at Holyrood and Westminster – and hope that it will convince them to vote No should another referendum ever be held. Perhaps by that time, the policy of allowing parliamentarians and members to campaign for a Yes vote will be moot.

Are their risks to this strategy? Yes. It will almost certainly be anathema to Labour voters who have stuck with the party through the referendum and vigorously fought to save the Union, and may serve to exasperate tensions within an already divided party.

But at this point, and in the face of brute electoral reality, what else can it do? It can’t dream up 300,000 left of center pro-Union voters to replace the ones it lost.

In many ways, is Labour is paying the price for complacency and taking voters for granted long before the white-hot heat of the referendum. In some parts of Scotland, Labour’s grip was so tight, it was joked that votes were weighed, not counted, and this complacency was ripe for the SNP to exploit as they made overtures to disillusioned and disaffected people in areas that had been habitually voting Labour for generations. Indeed, the referendum and general election may have exposed the difference between committed Labour voters and habitual ones, and the habitual ones were successfully picked off by the SNP for the referendum and general election.

Some may say that this is Labour’s problem which they brought on themselves with devolution and taking their traditional voters for granted. Tough on them.

Fine, but Labour’s problems today will be all of our problems tomorrow if they don’t succeed in winning back those voters, for if the party had not lost them (or if the Tories had more seats in Scotland) we would not be having this issue. But alas, this is the situation in which he find ourselves.

Going forward, Labour must offer an alternative that emphasizes its ambitions which have little to do with the constitutional issues and which emphasizes solidarity – economic, social, and cultural – with the rest of the UK. It needs to expose the SNP as constitutional and separatist obsessives while people starve, can't get a proper education, or can’t get timely medical care eight years after their first day in power.

With Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the UK Labour Party, the SNP’s claim to being the only true anti-austerity and “progressive” party in the UK has been blown out of the water, and all they have now to beat is the secessionist drum, which explains why they have repeatedly raised the prospect of another referendum in the hope that disenchantment with “Westminster” – to some extent manufactured – will drive Scots to demand another one.

In the face of this, Labour, the Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats must change the framing of the political debate from the constitution to real bread-and-butter issues where the SNP are vulnerable when such issues (like policing, education, and health) are afforded the much-needed scrutiny given that the SNP has been running Scotland since 2007, and they won back then by saying that they would do a better job than Labour. It’s high time that the pro-Union parties adopt this mantle of doing a better job, and use it against the SNP.

For too long, the SNP have been successfully playing the long game in their path to independence, and the results have been on display for all to see.

Therefore, there must be a long-game strategy for the pro-Union parties. Each of them must play to their own strengths and values to pick off people from the various factions of the SNP – left, right, and center. They must appeal to these people based on issues that matter to them outwith the constitutional questions, and persuade them to vote on that basis. Over time, this may lead to the cultivation of more pro-Union voters should there be another referendum. So yes, this is about emulating the SNP – in terms of tactics and long-term strategy.

After all, in order to prevent another referendum, there needs to be a pro-Union majority at Holyrood. On this point, some people may claim that Labour is more concerned about power than the country, but the thing is, having Labour in power at Holyrood is massively better than the SNP. The same goes for the Tories and LibDems, because they all played a part in keeping Britain together, and it is hard to see any of them making a referendum on separation part of party policy.

Bringing in Yes voters may be the first step of what needs to be a long-term effort to get Scotland away from the dividing line of being Unionist or Nationalist, or as some Nats would erroneously have it – “for or against Scotland”, and I certainly do not wish to see Scotland descend into becoming another Northern Ireland.

All three parties need to recover themselves in Scotland, if for no other reason than there still remains a right wing and a left wing. The Right is almost exclusively occupied by the Conservatives, whilst Labour and the SNP are fighting over the Left, and the LibDems are somewhere in the middle of all this.

For their part, the LibDems troubles stem from their involvement in the coalition government at Westminster with the Tories after the Tories had failed to obtain an outright majority following the 2010 general election. They were therefore vilified for propping up the Tories and enabling them to go through with policies such as the the increase in tuition fees (which they had opposed in the election), the privatization of Royal Mail, and controversial changes to the welfare system. The result was that they were heavily punished by voters throughout the UK, but especially in Scotland, where the Tories have been unpopular (and seen as anathema to Scotland) since the 1990's. In this year's UK general election, the LibDems lost all but one of their 11 seats in Scotland - having lost many of their voters to the SNP like Labour, and losing a generation of their best talent.

Only the Tories emerged more or less unscathed, though that's not much to go by given that they have only had one seat in Scotland since 2001 - which again, leads to the charge of "Tory governments we didn't vote for!" However, the Conservatives are almost solidly behind the Union, and few of their 400,000+ voters sided with independence in the referendum or switched allegiances to the SNP in the general election.

With the Labour and LibDem statements about letting in Yes voters and allowing free votes on separation, the Tories have begun promoting themselves as the only true party of the Union, with the hope that this will help achieve some sort of electoral revival for the party. However, my personal fear is that if the Right claims ownership of the Union, and the Union is seen as a right-wing entity, then where does that leave the Left? Some may undoubtedly come to the conclusion that the if the Right naturally supports the Union, then the Left naturally supports independence, and that is a charge I have been fighting against for the past three years, along with the notion that the United Kingdom is an inherently big bad “right wing” country from which little goody two-shoes “left wing” Scotland must escape.

The Union can only survive in Scotland if it has natural supporters on the left and right of society, and the last thing we need is people on either side feeling as though they are unwelcome, and at any rate, I feel that there is much that can be learned by people from different political thoughts working together and overcoming their differences, prejudices, and stereotypes.

Scotland needs to get back to the politics of solving problems that effect people on a regular basis, and each party has something to offer. The Tories can make an appeal being the party of low taxes, property rights, and free enterprise; the LibDems can take the lead on appealing to real concerns about the SNP centralizing Scotland’s polices forces and other civil liberties issues; and Labour can be the party what wants to deliver social justice. Along the way, they must also hack away at the false promises and empty rhetoric of the SNP and spell out clear reasons for why separation is not good, and why there is strength in the unity of the United Kingdom.

(For my part, I was just as happy to see Labour winning a council by-election, as I was to see the Tories win the first preference round of another by-election, before (closely and so unfortunately) losing to the SNP in the second round.)

For Labour, the Liberal Democrats, as well as the Tories and individuals and groups not aligned with any party, the winning message is not “Support the Union, end of story.” Rather, it is: “Support the Union because we believe our values and goals are best achieved within it, and we believe the Union confers enormous benefits and advantages, not just for us, but for all of the UK, with whom we should all firmly stand in solidarity and common purpose.” And as Dr. Arthur said, the arguments in favor of the UK are legion.

All three parties are committed to the Union because they see it as a means to achieve greater ends which separation cannot deliver, and they believe that this is the best for Scotland and the UK as a whole. They must make this case with repeated vigor and confidence while also outlining their agenda for Scotland if they wish to improve their electoral fortunes, and by extension, secure the future of the Union.

Strong and effective leadership will be needed by Dugdale, Davidson, and Rennie, so that these three parties – battered and wounded by the experience of the referendum and its aftershocks – can be comfortable in their own skin as parties that have a positive vision for Scotland within the UK, and have a positive and viable alternative agenda from that of the SNP. Some people will never come back to these parties, but with a coherent and realistic intellectual and emotional case fit for the 21st Century, I believe many will.

The next Holyrood election is less than eight months away. It is time to use our imaginations and think outside the box; time get cracking on our long-game.