Voting As One on Europe

/Britain's Union Flag and the EU Flag. Image Credit: Dave Kellam via Flickr CC

The campaign on Britain’s membership of the European Union well and truly got underway last week as Prime Minister David Cameron announced the date of the referendum to be June 23rd.

With modified membership terms, the British people will have their first say on Europe since overwhelmingly voting in favor of joining the EU’s predecessor, the European Economic Community (EEC, or the Common Market) 41 year ago, and the campaign promises to be a passionate and contentious battle between those who believe the UK’s future is in the 28-member bloc and those who believe that it will be better off outside of it.

As it currently stands, most opinion polls show that the British public are almost evenly divided on the issue, and there still substantial numbers of people who remain on the fence. From now until the day of the vote itself, there will be robust arguments and counter-arguments, claims and counter-claims for and against EU membership. Only then will those on the fence have to make a decision based on what’s best for themselves, their families, and their country – and everyone will render their collective verdict on whether to keep the membership or terminate it.

In an ideal world, there ought to be a supermajority requirement, so that in order for a vote in favor of changing the status quo (terminating membership, that is) to be valid, there would have to be substantially more than 50% plus one in favor of it, so as to ensure that when the decision is made, the vast majority of the population will be behind it.

Alas, this is not going to happen unfortunately, and so a simple majority will suffice. However, it should be more realistic to believe that whichever way the vote goes in total, the result ought to be respected, and the people of the UK should accordingly move forward as one.

However, this basic notion of democracy has been questioned by – you guessed it – the SNP. Indeed, it is no secret that the Nationalists have been banging on about calling another independence referendum should the UK as a whole vote to terminate its EU membership but the majority of Scots vote the other way.

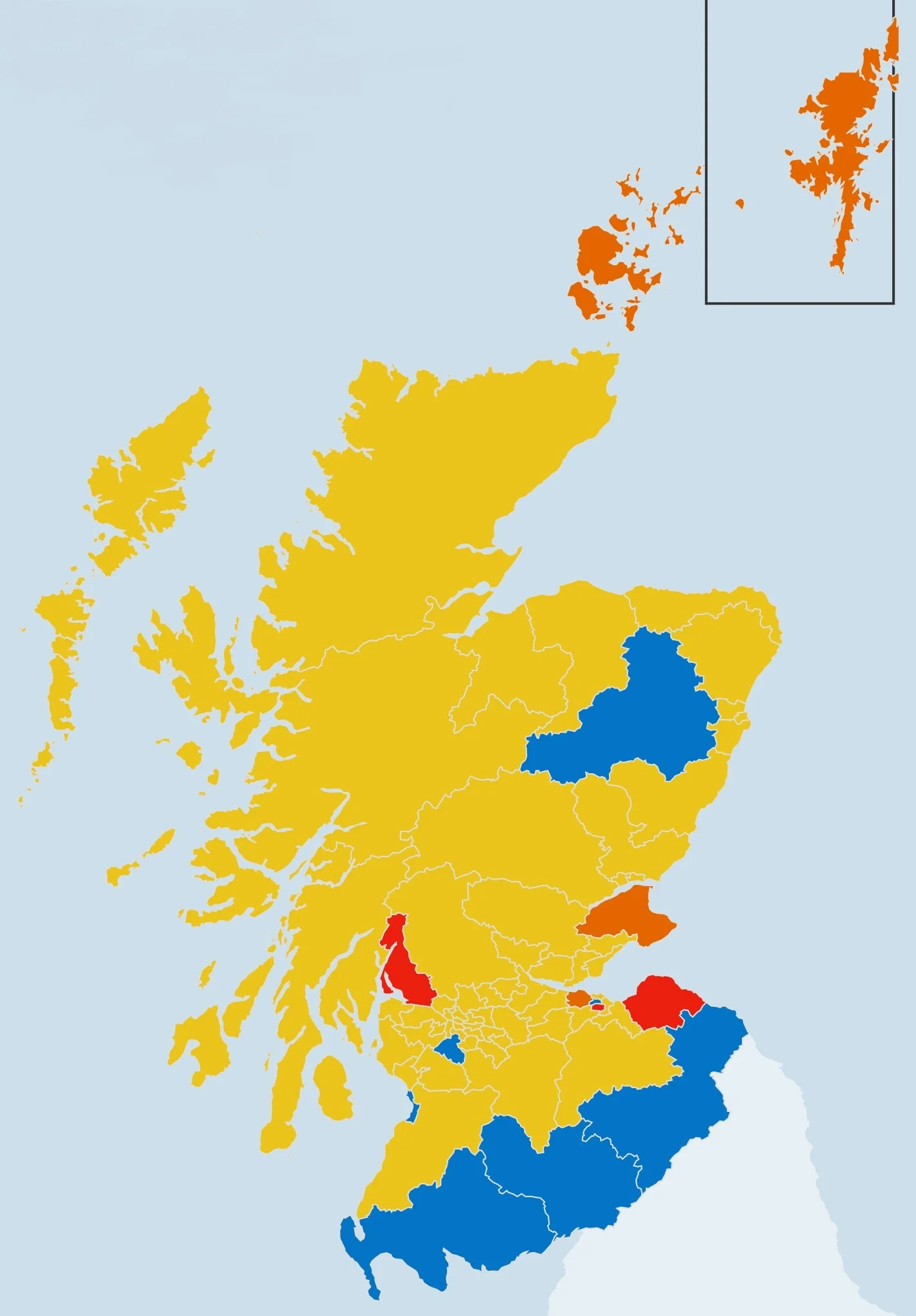

To be sure, the most opinion polls have showed that at the very least, Scots are more likely to vote in favor of the EU than their fellow Britons in other parts of the UK – England in particular, and the strength of the English “Leave” vote may well be enough to take Britain out of the EU without a majority of Scots backing it. This, claim the Nationalists and their supporters, will amount to Scotland being “dragged out of the EU against its will” and thus force the independence issue back to the surface – not that it really went away even after the decisive self-determination of Scots to keep the UK together – by giving Nicola Sturgeon the “material change” or “trigger” she has cited as the grounds for calling another referendum. Such an outcome, the theory goes, will result in Scotland voting for independence in order to stay in (or re-enter) the EU because the overall UK vote on the EU failed to go the way the majority of Scots wanted.

This attempt to effectively achieve the break-up of the UK by taking advantage of potential voting differences on Europe is not new, for the SNP tried this during the 1975 referendum when it was against the Common Market and hoped that Scotland would vote “No” to the EEC while the overall UK voted “Yes”. According to a working paper from the Sussex European Institute by Valeria Tarditi, the SNP viewed that referendum as a way to prove the “illegitimacy of the British government and its policies in Scotland”, and they hoped “that the opinions expressed by the Scottish people would be totally different from the rest of the UK and, above all, that in Scotland there would be a clear majority that opposed EC membership.”

As it was, the SNP hopes for this were shattered as Scots voted with their fellow Brits in favor of the Common Market – perhaps indicating that they viewed the EEC issue on its own merits, rather than seeking to use it for other means, as was noted by Labour MP John Mackintosh on the BBC as the results of that referendum were coming in.

Now the modern-day SNP is pro-EU, but the rhetoric with regard to how the rest of the UK feels about it has not changed, and with the date for the referendum set, they have been ratcheting up their saber-rattling by repeatedly talking up the possibility of another independence referendum at virtually every chance they get. Nicola Sturgeon has said that the UK leaving the EU without a majority of Scots will “almost certainly” trigger a second referendum and her predecessor Alex Salmond said that the pressure for it would be “irresistible.”

Along the way, the Nationalists have whined about the chosen referendum date – given that it takes place a month-and-a-half after the Scottish parliamentary elections, and therefore causes the two campaigns to overlap. Such overlapping, they have claimed, is just another “Westminster insult” toward the Scottish people. However, it’s more likely an insult to the Scottish people (along with the Welsh, Northern Irish, and the English – who hold assembly, local council, mayoral, and police commission elections on the same day as the Holyrood election) to say that they cannot be trusted to differentiate the two campaigns, just as they were able to do five years ago when they gave the SNP a majority in Holyrood while also voting in the UK-wide AV referendum.

In the end, as Alan Cochrane noted in the Telegraph, “David Cameron was always going to hold the vote when he thought he’d the best chance of winning”, just as Alex Salmond – with Sturgeon supporting him – chose September 18, 2014 as the optimal date for holding the Scottish referendum.

With regard to the upcoming EU referendum, this griping about the date, the potential outcome, and the fact the referendum is even being held is partly an exercise in SNP party management, because as also noted by Cochrane, the Nationalist First Minister of Scotland is on the same side of the EU debate as the Tory Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and having successfully bludgeoned the Labour Party over “standing shoulder-to-shoulder” with the Tories in common cause to save the Union and swelling the ranks of her party in the process, Sturgeon feels the need to put clear water between herself and David Cameron. To keep the more zealous of her party onside therefore, she picks fights with Cameron and the UK Government, and always reminds everyone that “Brexit” will likely result in agitations for “indyref2”.

In this vein, the SNP and those minded towards them have for years been trying to write off the EU question as the obsessions of Westminster, the Tories, UKIP, and the English. Not only is this cheek given their own constitutional obsessions, but it is a false premise given that around 60% of Scots are themselves “Euroskeptic” – slightly lower than the overall UK proportion – according most recent British Social Attitudes Survey. Nevertheless, it suits them to hype up the differences between England and Scotland, so as to further their independence agenda and claim that Scotland will be dragged out of the EU via English votes.

However, as former Labour MP Tom Harris bluntly wrote in his own column in the Telegraph, the reality regarding the EU debate and referendum is this: “it’s not all about you, Scotland.” Indeed, having watched as a “significant minority of Scots took to the airwaves and the doorsteps to explain their desire for a divorce from them” during the two year long independence referendum campaign, their “English, Welsh and Northern Irish compatriots have displayed a patience above and beyond what might be required of fellow citizens.” Now that the UK is having a referendum on EU membership, it should be plainly obvious that this about the United Kingdom as a whole and not about any one part in isolation of the others.

Above all, it must be remembered that the question on the referendum ballot will be:

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?

It will not say “Should Scotland remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”, nor will it say “Should England remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”, and still further, it will not say “Should Wales remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?” or “Should Northern Ireland remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”

Why is that? Because, in the most respectful of terms, none of them have EU membership; the United Kingdom does, and it should be abundantly clear that whatever the outcome of the EU referendum vote in any one part of the United Kingdom – however defined – it is the overall vote throughout the United Kingdom that matters.

This means that an overall UK result in which English “Leave” votes are strong enough to take the UK out without a majority of the other Home Nations is perfectly legitimate, and the same goes for a scenario in which the “Remain” votes of the other parts of the UK are enough to keep the UK in without a majority of the English. Both results are legitimate as they will represent the majority will of the British people in their totality, and should not cause resentment on the part of anybody so long as the vote is conducted fairly and held to the highest electoral standards.

Indeed, there is the possibility that the English vote will be split roughly evenly – meaning that the results among the rest of the UK in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales may be decisive in tilting the overall result one way or the other.

This is why David Cameron – as a British citizen and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom – will be campaigning throughout the UK, including Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, to press his case for keeping the UK’s EU membership. This is why every vote in the referendum will count equally wherever it is cast throughout the United Kingdom, and this highlights the need for every eligible citizen to be registered for voting and then actually vote on the day that really matters. It also shows the importance of retaining the BBC's UK-wide News at Six in Scotland, for it is important for people to know what's going on in the UK overall and get a UK-wide perspective on news which effects everyone in the UK - including Scotland, and this has been made clear by focus groups. With regard to the EU referendum, this is particularly important, because Scots will be voting alongside people who are not foreigners, but their fellow Brits and only the overall result matters.

Even if “Brexit” happens without a majority of Scots, it is not immediately clear that Sturgeon will make any quick moves to call for a referendum, or even if she will, for as explained by Martin Kettle in the Guardian and Joyce McMillan in the Scotsman, Brexit presents a myriad of issues for the SNP and makes independence far from certain. Indeed, if the cards are played wrong, the hopes among some in the SNP for a “Scotland stay/UK leave” vote in June may well backfire. There is certainly no guarantee that Sturgeon can achieve victory on a second referendum even in the aforementioned circumstances, and if she were to lose, it would almost certainly put off the independence issue for decades, if not terminally. So it is in Sturgeon’s own interest to vigorously and genuinely campaign – like Cameron – for a Remain vote throughout the UK, regardless of what some in her own party may be thinking.

Hopefully, as John Mackintosh said in 1975, most people throughout Britain will focus on the main issue of EU membership. They need to think about the vote and the implications for themselves, their families, and the country in which they live – the United Kingdom – and go forward together with the decision made together as one.