Getting Rid of the BTP at All Costs

/British Transport Police officers on duty in the London Underground. Image Credit: Gordon Joly via Flickr CC

This week in Scotland saw one of the more controversial aspects of the Smith Commission being brought up for discussion: the possible breakup of the British Transport Police, the specialist law enforcement force which is responsible for the policing of Britain’s railways.

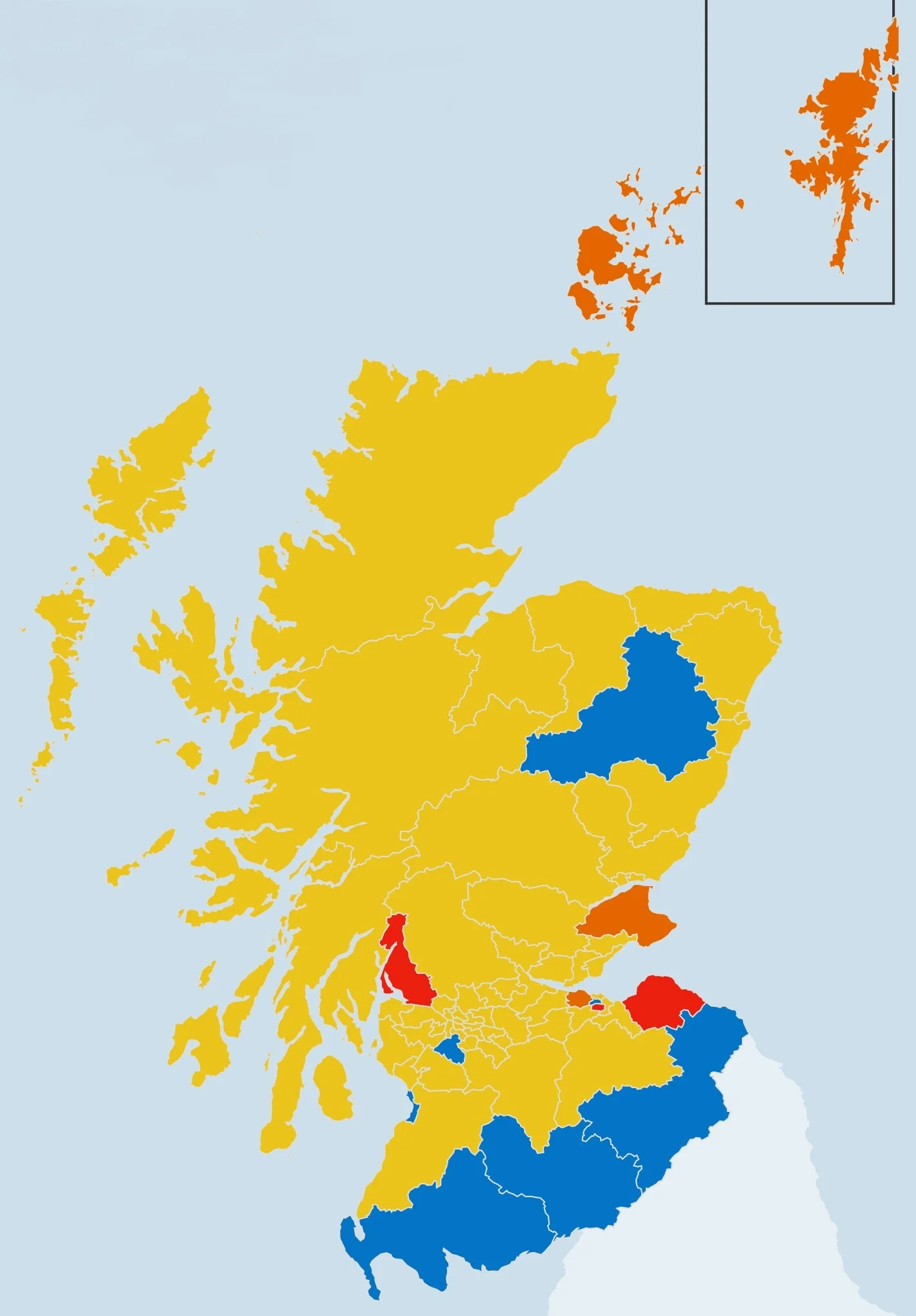

For those not familiar or needing a refresh, the Smith Commission was created in the aftermath of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum which saw the majority of Scots deciding to keep the United Kingdom together. In the closing days of the campaign, the three main pro-Union parties promised in the Daily Record (via the famous/infamous “Vow”) that with a “No” vote to separation, the devolved Scottish Parliament at Holyrood would receive more powers to exercise in Scotland, as opposed to the UK Parliament at Westminster (with Scottish representation as there always has been) exercising those powers in Scotland as part of the overall United Kingdom. With separation rejected, the commission was formed to recommend what should be devolved and among them was the Scottish BTP functions, and this was pushed through as part of the Scotland Act 2016.

Even before the final passage of the act, the SNP government had made clear its intentions to use this new power to absorb the BTP in Scotland into Police Scotland, the single national police force created by the SNP in 2013 by amalgamating the eight existing regional services. In September, the merger proposal was officially announced as part of the SNP’s program for government, and last Wednesday saw various police representatives in a round-table discussion about the merger plan with MSP’s on the Justice Committee at Holyrood.

Already, three railway unions and the BTP Federation had stated their opposition to the plan, with the federation expressing anger at the Smith Commission recommendation soon after it was made in 2014, saying that it was “both unjustified and unjustifiable.” Their main concern has been the potential loss of the BTP’s specialism and expertise, which make it unique from a force based in a particular geographic area, as well as the integrity of cross-border travel safety. For this reason, the BTP has offered to continue its services as a separate force in Scotland, but with oversight from Holyrood, rather than Westminster.

However, the SNP government has continued to press forward with the scheme in the belief that since all other policing in Scotland is under the jurisdiction of Police Scotland, then the Transport Police should be the same way and that integration would “ensure the most efficient and effective delivery of all policing in Scotland.”

The more generous remarks given on the subject in favor of the SNP’s position came from Police Scotland’s Assistant Chief Constable Bernard Higgins, who said the merger could work and that his force could police all the railways despite this being “massively complicated” and admitting that there would be “massive transition issues.” His statement broadly echoes that of the Scottish Government saying that specialist skills of the BTP would be maintained and could be achieved “from within our national police service.” He also gave assurances that staffing levels would be maintained and potentially supplemented by Police Scotland officers.

BTP badge from Dave Connor's Scottish Law Enforcement Insignia Collection. Image Credit: Dave Connor via Flickr CC

Such assurances were not enough for Nigel Goodband, chairman of the BTP Federation, who said that some of the experienced specialist transport officers would rather quit their jobs than not be BTP officers and that therefore, neither the SNP government nor Police Scotland could promise that the quality of service and expertise would be maintained. Some of this attitude stems from controversies with regard to the formation of Police Scotland and its handling of policing, and in its submission to the Justice Committee, the BTP Federation regarded the force as “still very much in its infancy” and that “no evidence to date has been able to state clearly what, if any, advantage there would be in dismantling the current BTP model of policing in Scotland and integrating it within a geographical routine form of policing.”

BTP Deputy Chief Constable Adrian Hanstock emphasized this point by stating that the BTP exists because its “specialism is so valued by the [rail] industry and passengers” and that railways required different policing from that of general law enforcement, which is specifically why it is difficult to merge into a geographic force (and why the federation is concerned about the possibility of transport officers being used to bolster Police Scotland). He was backed up by Nick Fyfe of the Scottish Institute for Policing Research, who pointed to a “distinctive culture and ethos in policing the railways.”

This culture and ethos is what makes the BST unique and allows it to transcend borders to provide a consistent specialist service, and for that reason, the federation is also concerned about the annual 21 million cross-border passengers and whether there may be interruptions to the “seamless” level of service they have come to expect.

This leads to something on a more fundamental level, which is that the British Transport Police is a service used and shared by rail travelers throughout Great Britain – a service which is visibly recognizable and the relatively the same wherever anyone goes, whether from Glasgow to London, or Cardiff to Manchester, or Birmingham to Edinburgh, so as to ensure that people get to their destinations safely. It is therefore representative something “British”, not only because of the name, but because of its mandate, jurisdiction, and service it provides throughout the island. The United Kingdom does not have a national police force, so the Transport Police is as close to such a force in the country.

All of this of course, is anathema for the SNP. Its members, including at senior levels, deny that Britain is a country and seek to characterize it as just a “state” or "invented construct" run from (big, bad) Westminster without a heart or soul, little in connection to people in Scotland, and certainly not doing anything of value or significance for them. It therefore suits the SNP government to fold the Transport Police north of the Border into Police Scotland and to not only extinguish a piece of shared Britishness – the closest thing to a national police force – from the Scottish landscape, but to effectively kill it entirely throughout the whole country and have one less relevant institution linking it together.

Despite evidence that merging the Scottish BTP into Police Scotland would be very complex (at a time when the national force is still coming to terms with its own formation), may result in the loss of specialist capabilities, and simply is not necessary for effective policing, the SNP seems content with pressing forward for the purpose of simply creating another difference between Scotland and the rest of Britain.

This is but probably a taste of the “independence at any cost” posture taken by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon when she claimed that separation “transcends the issues of Brexit, of oil, of national wealth and balance sheets and of passing political fads and trends.” However, these are important issues which must be considered and cannot be ignored if there is to be another referendum like the one in 2014, just as the complexities and warning with regard to the dismantling of the BTP and merging it into Police Scotland cannot be dismissed. As far as can be told, the BTP works as a specialist force policing the railways of Britain, but the SNP government is pursuing a strategy of making Scotland feel as though it's not part of Britain at any cost.

During his remarks at the Justice Committee discussion, BTP Deputy Chief Constable Adrian Hanstock asked: “If it's not broken, what are we trying to fix?”

That’s just it; there is nothing to fix.

A BTP helmet located at St. Paul's Chapel in New York City in remembrance of 9/11. Image Credit: C.S. Imming via Wikimedia Commons CC