“Were you up for Salmond (And Much More)?”: A Look Back at the Extraordinary UK General Election Results in Scotland

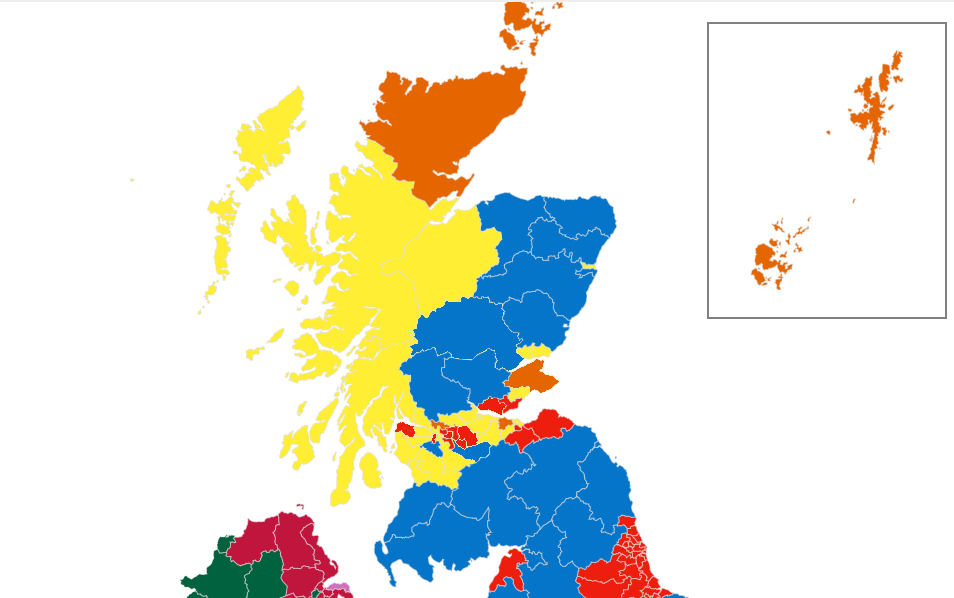

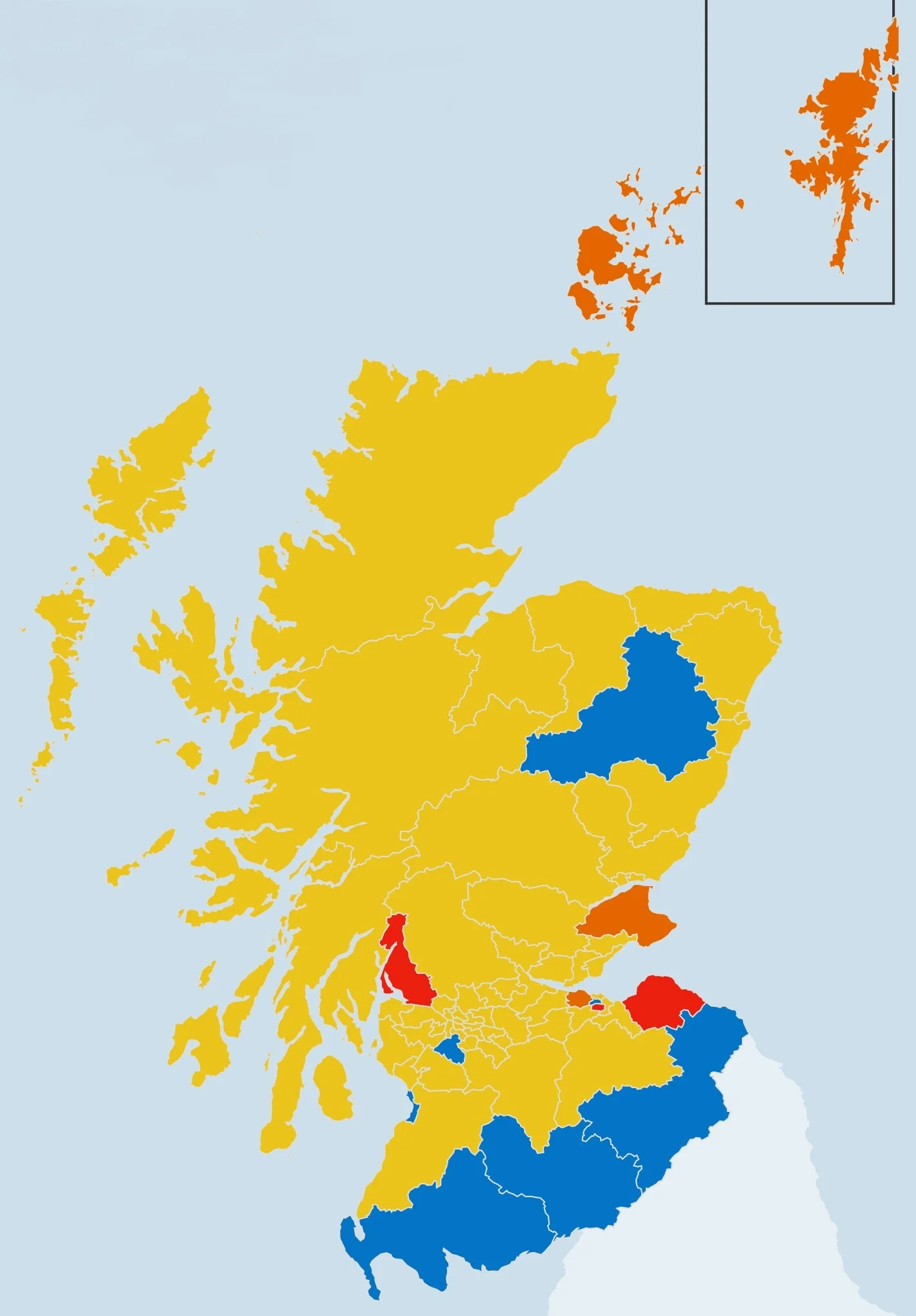

/The change in Scotland's political Map from 2015 to 2017. Image Credit: @ElectionMapsUK; cropped by Wesley Hutchins

It was a memorable night which began and ended in ways few had predicted, and which may have marked a yet another significant turning point in Scotland's political landscape, as well as the future of the United Kingdom.

At just after 10:00PM UK time, the exit poll was revealed to show that Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservatives would lose their majority, though remain the largest party with 314 seats. Labour under Jeremy Corbyn was projected to gain 34 seats for a total of 266, the SNP under Nicola Sturgeon would have 34, and Tim Farron’s Liberal Democrats were given a bump up to 14.

The immediate reaction was one of extreme bewilderment. On Twitter, the poll aggregator Britain Elects tweeted two words which expressed the astonishment of the nation and for the matter, the world: “Holy sh**.”

For the past couple of weeks, polls had been showing a narrowing of what had been a formidable lead for the Tories at the time when Theresa May had called for the election in April to shore up her position in the negotiations for the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union (aka, “Brexit”). A botched manifesto roll-out, a u-turn on elderly care policy, May’s refusal to participate in debates and her cool demeanor, as well as a general feeling of complacency and overconfidence in the party had turned off many voters. In contrast, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, all but written off for its biggest defeat since Michael Foot’s leadership in 1983, picked up steam as his avowedly left-wing and socialist platform connected with those tired of austerity and weary of Brexit – somewhat like our own Bernie Sanders in America.

However, most pundits still believed that even if May did not achieve the eye-watering majority of around 100 seats, she would still manage to retain a majority government, if only barely and she would at least be able to claim that she had her own mandate, as opposed to inheriting David Cameron’s. Now this exit poll was upending all those assumptions. The pound fell sharply, Twitter went crazy, and morning editions of newspapers across the country went to press proclaiming how the Prime Minister’s gamble had failed.

Shocking as this was with Theresa May potentially no longer at the helm of a majority government, more surprising with particular regard to Scotland was the exit poll showing the SNP losing 22 seats – a stunning reversal for a party that had achieved the incredible feat of winning all but three of Scotland’s 59 constituencies just over two years ago. A deeper analysis of the exit poll resulted in a list of seats that were likely to change hands, and among them were seats belonging to SNP deputy leader and Westminster group leader Angus Robertson (Moray) and former SNP leader Alex Salmond (Gordon) and they were at serious risk of losing that evening, along with other stalwarts of the party would have their parliamentary careers coming to an abrupt end. The poll also implied that all three main pro-Union parties were performing better than expected and would make significant gains at the SNP’s expense.

Following the initial reaction, there was disbelief and urges of caution. Elements of the Tories and the SNP – two of the parties of government in the UK – took the exit poll to task, with the former insisting that they would have a majority and perhaps a bigger one at that, and the latter saying its losses would be far more limited.

Indeed, within that first hour or so after the poll was released, it did seem as though the projections may have been off, at least to some degree. The first results that were declared in England were holds for Labour, but also featured significant increases in the Conservative vote – some of it coming from people who had voted for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in 2015. Surely if these were to be replicated in other places that were not safe Labour seats and/or in areas where Labour had been vulnerable to UKIP, then it would indicate the potential for more Tory seats and perhaps a majority Tory government.

On Twitter, there were reports of backtracking on the poll as the results came in one by one and showed trends contrary to what the poll had indicated, and if it had underestimated the Conservative vote across the UK, it may have also underestimated the SNP vote in Scotland as well – perhaps by a lot. Journalists, commentators, and partisans on all sides were expressing skepticism. In Gordon, where initial reports had Alex Salmond and his Conservative opponent in a tight race, now it was being reported that the former first minister was out in front.

As much as many of us wanted him out of Parliament, it was simply inconceivable that he would lose and that so many SNP seats would flip to a pro-Union party in part because of his name recognition in particular and the staggering majorities of many SNP MP’s more generally which have to be overcome. For this reason, the Tories, Labour, and LibDems expressed extreme caution in an effort to manage expectations and avoid potential disappointment. “Was it possible?”, many of us asked. Yes, but not probable and another reason was the concern that in some seats, the votes of those parties would cancel out each other, so that even though a majority of constituency voted for a pro-Union candidate, it got an SNP MP due to the split vote. It seemed more realistic that the SNP would lose 15 seats at most.

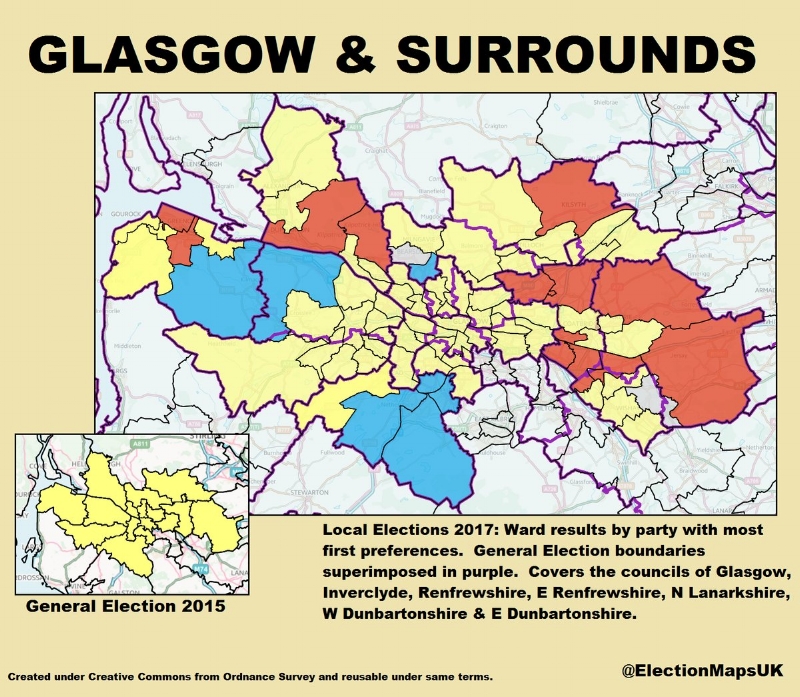

As the counting continued to progress however, it became apparent that something was afoot. In the North East and Perthshire, it was reported that the three Union parties were experiencing increases in vote share, as well as in the South of Scotland, but that the Tories were particularly showing strength against incumbent SNP candidates. More striking was what was happening in the Greater Glasgow area, where Labour had been dominant for generations, but the SNP had become the new game in town. Once insurmountable Labour parliamentary majorities had been replaced with towering SNP ones in the city which had voted “Yes” for separation and ended Labour’s 37 year control of the city council to put the SNP in charge. Even in the event that Labour or any other party benefited from a swing against the SNP, the general feeling was that it would not be enough to overcome the entrenched nature of the SNP in this area.

And yet, by midnight UK time, Labour was having reason to be increasingly optimistic as the counting continued and showed them as least keeping up with the SNP in the Glasgow area and Clydeside seats. On the other side Scotland, it was also reported to be in first place in East Lothian and holding on well in Edinburgh South, where Ian Murray appeared to be picking up a larger majority than in 2015. Meanwhile in Edinburgh West and East Dunbartonshire, the LibDems were running close with SNP, though they too were feeling very confident about their chances at retaking them.

Then at just after 1:00AM in the UK, the first Scottish result came in the form of Rutherglen and Hamilton West, just to the southeast of Glasgow where Scottish Labour had begun its campaign, and it was a Labour gain. On an 8.9% swing, Gerard Killen had overturned Margaret Ferrier’s 9,000 vote majority and won the seat with a majority of 265 even as the Tories and LibDems also made gains here.

The shock of this result could not be overstated: a constituency which had utterly rejected Labour only two years earlier for the SNP in the wake of the independence referendum was now returning a Labour MP against virtually all projections and predictions. In my own review of the Scottish constituencies likely to change hands, I did not pay attention to any of the Glasgow area seats, save for East Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire. To be sure, it was only one result, but the 9,000 vote majority Labour managed to overturn was bigger than majorities in other nearby constituencies, which meant that they were in play and that it was possible that the exit poll had been accurate after all.

As it was, next to declare was Paisley and Renfrewshire South, where a majority of 5,600 stood between Labour and Mhairi Black, who had defeated Labour’s Douglas Alexander in 2015 to become the youngest parliamentarian in over 300 years. She faced a closer fight than expected, though she stayed on with a significantly reduced majority of 2,500 in part because of the division of the vote between the three pro-Union parties; there were more than enough votes from the Conservatives and LibDems which could have been used to block Black by lending them to the Labour candidate, who was her closest opponent. Indeed, there had actually been a swing from Labour to the Tories, suggesting perhaps that the attacks on Labour’s stance on the constitution/separation – including Nicola Sturgeon’s last minute revelations – may have had an impact. Not for the last time this night, a majority pro-Union constituency would end up with a separatist MP who had a smaller majority than last time and therefore was more realistically beatable. The only question now was: “How many more?”

Indeed, many of us were bracing for this to happen in a great many seats, which would blunt any significant advance against the SNP and allow them bragging rights and an excuse for another divisive referendum. To be fair, they would likely do this with 34 MP’s as much as with 45 MP’s – a majority of seats being all that mattered. However, it would definitely weaken their case with the former and give us hope that Scotland would become more politically balanced.

West Dunbartonshire (containing Clydebank, birthplace of some of the great ships of the Cunard Line at the old John Brown’s shipyard) was the next result to declare, and once again, the sitting SNP MP was re-elected with a reduced majority 2,200, which could have been overcome with more tactical votes for the Labour candidate from other pro-Union candidates. The silver lining of course was that the rising vote share for all three parties indicated that at the very least, there was a backlash against the SNP, and that just as towering Labour and LibDem majorities could be toppled as they were in 2015, so could SNP ones in 2017. Hopefully, it would be just a matter of time before what happened in Rutherglen would be repeated across the country.

Sure enough, as the 2:00 hour approached, reports were coming through saying that in East Dunbartonshire, where the vote had been so close as to say that “John Swinson” had been elected, the Liberal Democrats were increasingly confident that Jo Swinson was pulling away from SNP incumbent John Nicolson to reclaim the seat she had held from 2005 to 2015. Labour was all but claiming victory in East Lothian, and the SNP had pretty much thrown in the towel on border constituency of Berwickshire, Roxburgh, and Selkirk – saying that while there vote had held up, the LibDem vote had transferred to the Conservative candidate, John Lamont. Meanwhile in the Western Isles (Na h-Eileanan an Iar), the difference between Labour and the SNP’s Angus MacNeil was said to be in the hundreds.

Then another declaration, this time from the Ayrshire seat of Kilmarnock and Loudoun, which stayed with the SNP’s Alan Brown, whose majority was reduced, but was still significantly ahead because of a swing which mostly benefitted the third-placing Tories while the Labour vote remained mostly flat.

Thankfully however, the next declaration wasn’t so much just good news as it was a major upset: long-time SNP MP Mike Weir lost his Angus constituency to the Conservatives. This is was one of the areas that had been on the bubble for changing hands, though more likely to stay put than not. Now, here were the Tories overturning an 11,000 vote majority to take a seat with a 2,700 vote majority which they had targeted for years in an area that had been part of their old Scottish heartlands before the SNP came along. Labour and the LibDems also benefited from the swing against the SNP, but it was mostly for the Tories and they came out on top in spectacular fashion as it was starting to become clear that the SNP may be in for a rough night.

The next results from Dundee weren’t surprising given its status as a “Yes City” during the referendum and both of its SNP MP’s were re-elected with reduced, but still substantial margins as Chris Law (Dundee West) and former SNP deputy leader Stewart Hosie (Dundee East) fell below 40% of the vote share and the other parties gained. Interestingly for a city in which Labour and the SNP have traditionally been the top vote-getters, the Tories edged out Labour for second place in Dundee East – yet another sign of that party’s revival in Scotland.

After 2:00AM came the results from several constituencies and therefore a clearer picture of new political landscape. In quick succession, East Kilbride, Strathaven and Lesmahagow, Paisley and Renfrewshire North, Falkirk, and the Western Isles (Na h-Eileanan an Iar) emerged with re-elected SNP MP’s and it was the same story as with the other ones: substantial swings away from the SNP and the pro-Union parties putting on votes to cancel out each other to allow the SNP candidate to win. All of these were seats previously held by Labour and Labour was the main challenger, but surges in Conservative support helped to prevent Labour from winning and knocking the SNP down another peg.

It was around this time that the result in Perth and North Perthshire rested on a knife-edge as the margin between SNP incumbent Pete Wishart and Tory MEP Ian Duncan was only 36 votes, and that a recount was underway at the request of the Tories, for whom this seat was one of their top targets, and had been since they lost the predecessor seat of Tayside North in 1997. Winning here against another veteran SNP figure here would be hugely symbolic and mark the return of Perthshire to being Tory country.

However, the next result to come forward provided that symbolism. In Moray, the Tory candidate Douglass Ross defeated Angus Robertson – overturning a 9,000 vote majority to oust the SNP’s leader at Westminster and ending the SNP’s hold on another area that had previously been a Conservative heartland. This was a “Portillo moment” in the highest sense and Robertson became a major casualty in what appeared to be a pro-Union wave across Scotland that was at least in some way reversing the SNP tsunami two years ago. Surely at this point, there were some lower-profile SNP MP’s and candidates who were starting to wonder: “If it could happen to him, what about me?”

A few minutes later, Glenrothes in Fife was declared to be an SNP hold, but this was followed by Labour’s surprise victory in Midlothian, where Danielle Rowley overturned Owen Thompson’s 9,800 vote majority and retook the seat for her party with 885 votes to spare. Another close race concluded in Inverclyde, where Labour came within 384 votes of retaking that constituency from the SNP – another place where a few tactical votes could have made the difference.

Over in Ochil and South Perthshire meanwhile, tactical voting may have indeed made a difference with the Conservative Luke Graham gaining the seat from Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh, a high-profile and veteran SNP figure formerly of Labour and the Tories. While more attention had been paid to the very real possibility of the North Perthshire seat switching hands, the South Perthshire seat was seen as less likely to change and the last two months of projections showed it being a likely SNP hold. It was therefore surprising to see Ahmed-Sheikh lose this seat, but then again, this was an election which throughout the UK as a whole, was producing results previously unimaginable. South Perthshire was now blue once again after 20 years and it seemed that its northern counterpart would soon follow.

Meanwhile, the SNP successfully held North Ayrshire and Arran, where a 13,500 vote majority against Labour in 2015 had become a 3,600 vote majority against the Conservatives in an area they had represented for the most part until the 1980’s when Labour started winning here, before eventually ending up with the SNP via Patricia Gibson. In East Renfrewshire, her fellow party colleague Kirsten Oswald was not so lucky as she went to defeat at the hands of Conservative candidate Paul Masterton. This seat, also historically solid Tory territory until 1997 when it voted for Labour’s Jim Murphy, it then SNP in 2015, and was now back in Conservative hands with a majority of 4,700.

On the other side of the Clyde in East Dunbartonshire, Jo Swinson made her political comeback. Polls and projections had this being a close-run deal, but as it turned out, Swinson took back her old seat with a comfortable majority of over 5,300 votes against John Nicolson’s 2,000 vote majority two years ago. This was the first Scottish seat won by the Liberal Democrats, as well as their first net gain of the night, with hopefully more to come.

Indeed, if what was being said on Twitter indicated anything, there would in fact be more. Reports were coming in to claim that SNP majorities were falling everywhere as Labour, the Tories, and LibDems were all eating into the SNP vote from 2015, and that the party was facing trouble in Glasgow. Glasgow of all places, where they had been given control of the city council just weeks before. Labour in particular was starting to feel optimistic about retaking some seats in the city.

Perhaps this switch had to do with the reaction against another referendum, but also likely due to Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-austerity appeal to many of the soft “Yes” voters who could be persuaded that they could get the government they wanted throughout the UK and not just in an independent Scotland. Indeed, given the financial difficulties and austerity which a separated Scotland would likely have to go through, the potential argument from Labour may have been that in fact, the only way to get the kind of government they want is by sticking with the UK and signing up with Corbyn and Labour.

Glasgow rapper Darren McGarvey – aka Loki – is a known supporter of independence, but has become very critical of the SNP for their cautiousness, lack of a radical agenda, and focusing too much on…you guessed it, independence. He stated on the BBC that Corbyn – who began the last day of Labour’s campaign in the city on Buchanan Street – had “called his bluff” by proposing an agenda that was “genuinely left wing and of genuine substance”, and that while he would still vote for independence in another referendum, this wasn’t what the vote was about and therefore why he had voted Labour. Perhaps there were many others in the city of the same mindset and voted accordingly.

Meanwhile, there had been rumors and perhaps early indications that both Aberdeen North and Aberdeen South were going to flip from the SNP to Labour and the Tories respectively, which would have been surprising since the SNP was projected to hold the former. However, it was revealed that Aberdeen North had been held by the SNP’s Kirsty Blackman with a majority of 4,100 votes, while Aberdeen South was still counting. In Glasgow East, incumbent MP Natalie McGarry had been elected under the SNP banner as she defeated Labour’s Margaret Curran, but had resigned from the party whip after allegations of financial impropriety regarding her involvement Women for Independence organization during the referendum. Her SNP replacement, David Linden, held on to the seat with just 75 votes ahead of Labour, whilst the Tories doubled their vote. Glasgow Central was a much less tight affair with Alison Thewliss being returned with a majority of 2,267.

Up north, there was hardly such relief for the SNP has Alex Salmond arrived at his count in Aberdeen. It is clear that we wasn’t happy with the less-than-desirable news about the Tories possibly winning his seat, as well as perhaps knowing of the fate of his colleague Angus Robertson next door to him. By this time, a total of seven SNP MP’s were already gone, and the night was far from over.

Just after 3:00AM, Glasgow North East was declared to be a gain for Labour via candidate Paul Sweeney. They had lost it in 2015 when the SNP’s Anne McLaughlin took the seat on a swing of 39% which was the biggest swing of the election back then and memorably “broke” the BBC’s swingometer (prompting the Beeb to “recalibrate” it). Now Labour was reversing that with a swing of its own to take the seat back with a majority of 242. All things considered and with having a Glaswegian MP once again, this was becoming a good and better than expected night for Labour. More close results were announced from Dunfermline and West Fife, where the SNP’s Douglas Chapman held on with 844 votes over Labour, and in Lanark and Hamilton East, where the Tory surge propelled them to within 266 votes of toppling Angela Crawley.

Then after being all but known as a matter of fact, the result from East Lothian at last revealed that Labour’s Martin Whitfield had regained the constituency from the SNP’s George Kerevan – overturning his 6,800 vote majority and winning by 3,000 votes. East Lothian had been a big target for the party and as far as most commentators (myself included) where concerned, it was their only realistic prospect for a gain in Scotland. Indeed, a surge in the Conservative vote gave proof for the reasoning behind why this seat, if it were to flip from the SNP, would go to them and not Labour. However, it wasn’t enough as the increase in Labour vote – albeit smaller than that of the Tories – was enough against the declining SNP vote to put Labour on top.

Back in Glasgow, the SNP’s Patrick Grady held Glasgow North with a reduced majority of 1,060 votes over Labour and down south, the Tories pulled off another surprise victory when Bill Grant gained Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock from the SNP’s. The old Ayr constituency was once a solid Conservative seat at Westminster and thus, this represented yet another area going back to Tory blue. Minutes later, Aberdeen South also returned to its Conservative ways when Ross Thomson defeated the SNP’s Callum McCaig. Then there were two more holds for the SNP in Airdrie and Shotts and Glasgow South with majorities of 195 and 2,027 respectively over Labour. They SNP also held on to Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey, where two years ago, Drew Hendry had defeated Liberal Democrat Danny Alexander, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury during the Cameron-Clegg coalition government. Hendry’s majority, as with everywhere else had been reduced, but he was nearly 5,000 votes ahead of his nearest challenger, who was a Conservative as the LibDems had fallen to fourth place.

Down south in Fife, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s old constituency of Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath returned to Labour via Lesley Laird with a majority of 259 over the SNP, while in Edinburgh, Tommy Sheppard held on to Edinburgh East with a 3,400 vote majority over Labour. Then at last came the result from Perth and North Perthshire: Pete Wishart squeaked back into Parliament by the skin of teeth with a majority of just 21 votes! This was a seat that had been consistently projected to swing to the Conservatives via candidate Ian Duncan, even if only by a few votes in his direction, and with the loss of Angus Robertson and Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh, it seemed somewhat inevitable that Wishart would go as well. Then again, nothing in politics seems to be inevitable these days and if anything is possible, the re-election of Pete Wishart was one of those things. Still, Wishart’s previous majority had been 9,600 and with Labour and the LibDems increasing their respective vote shares in a constituency they knew they didn’t have a chance of winning, it was another story of the three pro-Union parties putting up votes, canceling each other out, and letting the SNP in through the back door.

It was the same story in Glasgow North West – an area once represented by Labour’s Donald Dewar – where Labour came up short against the SNP by 2,500 votes, as well as Glasgow South West, where the SNP’s Chris Stephens hung on by an even tighter margin of only 60. However, there was good news from Coatbridge, Chryston, and Bellshill, where Labour’s Hugh Gaffney overturned an SNP majority of 11,500 votes and took back another former heartland seat for his party with a 1,500 vote majority. With this win, Labour was now expecting to finish the night with seven seats in Scotland, with Ian Murray expected to eventually emerge with an increased majority in Edinburgh South.

It was around this time that SNP politicians and members (including Alex Salmond, still await the results in his Gordon constituency) looked at the rest of the seats to declare and thought it safe to begin banging the drum on how the SNP won the election with the majority of Scottish seats – attempting to downplay the number of seats lost. As it was, the party did go on to hold on to Linlithgow and East Falkirk with a majority of 2,900 over Labour, as well as Cumbernauld, Kilsyth, and Kirkintilloch East – also over Labour with a majority of 4,200 votes.

Then there came two critical victories for the Liberal Democrats; retaking Caithness, Sutherland, and Easter Ross and Edinburgh West. The latter seat was a big LibDem target, especially after they had retaken the overlapping Holyrood constituency last year and with candidate Christine Jardine, they overturned former SNP MP Michelle Thomson’s 3,200 vote majority against them two years ago and took back the seat with 2,900 votes to spare. The former seat in the Highland council area was another former LibDem seat once held by John Thurso until he was defeated by the SNP’s Paul Monaghan (of RT fame), but was not included in most projections as flipping from the SNP. Interestingly, the LibDem vote was almost unchanged from 2015, but a massive swing from the SNP to the Conservatives doubled the Conservative and brought the SNP down enough to deliver the seat to LibDem candidate Jamie Stone with 2,000 votes to spare. Perhaps a case of “accidental” tactical voting?

At any rate, the Tories found victory elsewhere with a string of significant gains. In Berwickshire, Roxborough, and Selkirk – jokingly known as the “John Lamont Seat” because of him standing there at the last three elections – was finally won by John Lamont. Two years ago, he had narrowly lost the seat by 328 votes, but now won it from the SNP’s Calum Kerr with a whopping 11,000 vote majority and 54% of the vote as SNP and LibDem votes transferred to the Conservatives. Meanwhile, in West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine, Andrew Bowie won with nearly a 8,000 vote majority over the SNP, and in Stirling, Stephen Kerr squeaked by with just 148 votes to spare over the SNP to become the first Tory MP representing it in 20 years since Michael Forsyth.

By now, it was after 4:00AM UK time and the exit poll which was treated with caution at the beginning of the night was really looking quite accurate. There were four more SNP victories in central Scotland and the south: Livingston, where Hannah Bardell won with reduced, but comfortable majority of 3,878 against Labour; Motherwell and Wishaw, which returned Marian Fellows with 318 votes over Labour; Edinburgh North and Leith, a seat which was heavily contested, but resulted in Deidre Brock hanging on with 1,600 votes to spare in a roughly three-way race with Labour and the Tories; and Central Ayrshire, where Phillipa Whitford’s majority was sharply reduced as voter swung from her to the Tories and the Tories came within 1,200 votes of wresting the seat from her.

This string of SNP wins was finally followed Ian Murray’s triumph in Edinburgh South. Two years previously, he hang with an increased majority of 2,600 votes against the SNP wave as the rest of his party was decimated across Scotland; this time, he increased his majority still further to an enormous 15,500 votes and with 55% of the vote – the biggest majority and largest vote share in this year’s election in Scotland – and he was now one of seven Scottish Labour MP’s heading to Westminster as the party was seemingly being revived from political oblivion. Murray was also first of the three pro-Union MP’s after 2015 to have his result declared, with LibDem Alistair Carmichael and Tory David Mundell still awaiting the declarations in their constituencies.

Meanwhile, the SNP held the UK’s largest constituency, Ross, Skye, and Lochaber in the Highlands. Once the seat of the late Charles Kennedy, it fell to Ian Blackford (now the SNP's leader at Westminster), who ousted the former leader of the Liberal Democrats with a majority of 5,100 votes. This time, even though his vote share declined, his majority grew to 5,900 votes as overall turnout fell and a decline in the LibDem and SNP vote was matched with a rise in the Conservative vote which has not enough for the Conservatives to win this seat. In Edinburgh South West, the Conservatives came within 1,100 votes in a three-way fight for taking former Chancellor Alistair Darling’s old constituency, but the SNP’s Joanna Cherry held on and prevented what could have been a return to Tory blue this area once represented by Sir Malcolm Rifkind as Edinburgh Pentlands.

However this disappointment was overcome by what was biggest upset of the night in Scotland: Alex Salmond lost his Gordon seat to the Conservatives. All throughout the campaign and into the night, the thought of dethroning a man, who it must be conceded, has been a political giant and changed the trajectory of Scottish – and to some extent, UK – politics, was an enticing yet dim prospect exactly because of his stature. Even with the favorable conditions for the Scottish Tories – having won the council elections in the Gordon area last month – and the exit poll showing that he was in trouble, it was somewhat expected that Salmond would pull out a victory, if only a narrow one.

However, this was already one of those nights when a big name and a towering majority hardly mattered. The fact that he lost and the scale of the defeat – over 3,000 votes behind Tory candidate Colin Clark – couldn’t have made it clear that this was a big win for the Tories (beyond their dreams) and a historic moment which represented just how severe the backlash had become against the SNP over a potential second referendum and other policies, as well as their grip on the political scene, which was started by the former party leader and first minister himself. When Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson talked up the possibility of taking Gordon based on the local election results, Salmond said that she was arrogant to “continue the line of ‘we’re going to take this seat, and we’re going to take that seat’. Once it doesn’t happen, it’s very bad news for Ruth Davidson’s credibility.”

Now people will live on to ask the question: “Were you up for Salmond?”

The news of Alex Salmond’s defeat had hardly been absorbed when news came that his former constituency of Banff and Buchan – were he had started his parliamentary career – had returned to the Conservatives 30 years after he had defeated Sir Albert McQuarrie, the “Buchan Bulldog”. His successor to the seat, Eilidh Whiteford, had been the MP since 2010 when Salmond stepped down to focus on his jobs as an MSP and First Minister of Scotland, and at the last election, she held it with majority of over 14,000 and a 60% vote share. This year, her vote plunged by 21% as David Duguid of the Conservatives overturned that margin to win the seat by almost 3,700 votes – a remarkable swing of 20.2%.

This was a massive earthquake result as with Gordon, because few people believed that Banff and Buchan would flip to the Tories and the party itself believed that both seats were out of their reach. At best, there may have been a swing in favor of the Tories, but only that. However, as many people have noted, not only were there strong feelings against another referendum, but also dissatisfaction with the EU and adherence to the Common Fisheries Policy, which some in the North East fishing industry believe has been harmful. Combined with this being an area with conservative (with a small “c”) tendencies, and a decision between the pro-EU SNP and the Tories promising to deliver Brexit, perhaps the result should not have been surprising, but it was still stunning.

And yet, this dramatic night still was not over with five seats still left to declare. In one of those seats, North East Fife, a second recount was underway after the Liberal Democrats were ahead by two on the first count and by just one vote on the second. If this result was to stand, it would have meant that the LibDems would have at least four seats in Scotland – with Orkney and Shetland still to declare if Alistair Carmichael would continue to be its MP.

It was now 5:00AM and while virtually all attention was on the elections to Westminster, there was a by-election to fill the Holyrood seat of Ettrick, Roxborough, and Berwickshire which had been vacated by John Lamont when he announced his candidacy for the overlapping Westminster seat of Berwickshire, Roxborough, and Selkirk. Aside from its connection to the overall general election, this by-election also gained some notoriety for featuring Alex Salmond’s sister Gail Hendry as the SNP’s standard bearer here. Almost expectedly, the Conservatives held on the seat with ease as Rachael Hamilton took over from Lamont, who as noted above, won the Westminster seat.

In a sign of the times for the Scottish Conservatives, they were running low on people to fill the gap left behind at Holyrood by Ross Thomson, who was going to Westminster to represent Aberdeen South. Unlike Lamont who represented a constituency, Thomson was a regional list member for the North East region – having been elected from a list of Tory candidates on the basis of the proportion of the vote that they had received in the region last year. According to Scottish Parliament rules, his vacancy is to be filled by the next person on the list at the time of the election last year, but as reported by the BBC, Colin Clark (now MP for Gordon) and Kirstene Hair (now MP for Angus) were also on the North East region list for the Conservatives and another person, Nicola Ross, had quit the party. Excluding her, they are down to Tom Mason, their last person on the North East list and if something happens to him or any other North East Tory members, then those seats will not be filled until the next Holyrood election in 2021.

One way to look at it – as mentioned by the BBC’s Philip Sim – is that the Scottish Tories, once left for dead, have revived to the point where there are more positions for them to take up than there are of them.

That issue wouldn’t befall them in Argyll and Bute, where they put up a good fight against Brendan O’Hara, but came up short by 1,300 votes – having slashed his majority by around 7,000 votes. The Conservative surge here had displaced the previously dominant LibDems down to third place and the Conservatives back in the running here for the first time since the seat was created in 1983.

However, the LibDems would prove their resiliency elsewhere with Alistair Carmichael holding on to Orkney and Shetland. Except for a fifteen period from 1935 to 1950, this area has been a stronghold of Liberals and Liberal Democrats since 1837 and they have won every general election here since 1950, which is the longest active streak for a party in any British parliamentary constituency. The SNP surge in 2015 and an attempt to legally remove Carmichael from office due to the “Frenchgate” affair almost brought that to an end, and though he survived, questions remained about his future. Would he stand for election again and if so, would the SNP be back to finish him off? As it turned out, he did stand again and won re-election with a vastly increased majority of 4,500 votes, which is lower than what he had in 2010, but significantly more comfortable than the 817 votes he survived on in 2015. Not only that, but he was now one of four LibDem MP’s from Scotland as the party fought its way back from irrelevance, as well as the second of the three pro-Union MP’s who survived in 2015 to have his result declared, with David Mundell’s declaration not far behind.

Before him though was the declaration of the seat next door to his – Dumfries and Galloway – where Alister Jack defeated Richard Arkless with a majority of 5,600 votes, resulting in another historically Conservative area, like so many others that night, returning to blue. Afterward, the result for Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale, and Tweeddale was announced and David Mundell emerged victorious with an expanded majority of nearly 9,500 votes – the biggest he’s ever enjoyed since his first election to the Commons in 2005. Having been the lone Scottish Tory MP for twelve years, Mundell was on the receiving end of the joke about there being more giant pandas than Tory MP’s. Now having definitively defended his seat with a bigger majority, the Secretary of State for Scotland was being joined by 12 other colleagues as the Scottish Conservative revival reached a new level.

At 6:00AM, there was now only one seat left to declare: North East Fife, where only one vote stood between SNP incumbent Stephen Gethins and his Liberal Democrat challenger. A third recount was underway and there was the real prospect of a new counting team being brought in and/or that the race would come down to a coin toss should this recount produced a tie. Finally at around 6:30AM, it was announced that Gethins had held on by just two votes, a far cry from the majority of 4,300 he enjoyed in 2015, but that was all he needed to stay on. In fact, most of the swing against him benefitted the Conservatives, but the LibDems remained by far the second-place party and they considered a legal challenge.

However, for all intents and purposes, all constituencies had declared and full and the end result on this dramatic and historic night was that the SNP fell to 35 seats, while the Conservatives, Labour, and the LibDems rose to thirteen, seven, and four seats respectively. In term of vote share, the SNP finished with 36.9% of the vote, followed by 28.6% for the Conservatives, 27.1% for Labour, and 6.8% for the Liberal Democrats.

Those seat totals and percentages reveal an election night which was truly astounding, not only because of what happened, but because of the scale and the extent.

Regardless what the SNP spin doctors and their most fervent supporters (or are otherwise trying to convince themselves and anyone who will listen), this was a devastating night for their party. In one stroke, they lost 21 seats, watched their vote share plunge by 13 points and they shed half a million voters, and along the way, some of their biggest names disappeared from Westminster – Angus Robertson, the deputy and Westminster group leader; Mike Weir, the chief whip; international trade spokeswoman Tasmina Ahemd-Sheikh; and of course, their foreign affair spokesman and former party leader, Alex Salmond.

Yes, they retained the majority of Scottish seats and remain the third biggest party at Westminster, but this already a forgone conclusion from the beginning of the campaign, because the SNP had 56 seats last time around and steep majorities in most of them which were believed to be very difficult too overturn. It was also known that the party would likely lose some seats, with the only question being: “How many?” What was surprising and what they cannot ignore (try as they might) was that they ended up with vastly fewer seats than almost anyone expected and that it could have been worse as some of those vaunted majorities all but evaporated.

The reality is that the SNP got squeezed on all sides as the three pro-UK parties all tore into its support from 2015. Rural areas in Perthshire and the North East which had once been the bedrock of SNP support since the 1980’s and 90’s were now reverting back to the Conservatives and their new heartlands in the Central Belt were on shaky ground too as Labour and the LibDems were making a comeback. Indeed, one reason why this night was as surprising as it became was due to the unexpected strength shown by those two latter parties which had been all but been left for dead in Scotland.

In particular, Labour was only expected to pick up one seat, East Lothian – if that – and there were some doubts about the party hanging on to Ian Murray’s Edinburgh South constituency, so that there appeared to be the possibility of Labour being completely wiped off the political map. However, it emerged with six new seats – all of which had been lost to the SNP two years ago and all of which they took back in an election which seemed to partially reverse the nationalist tide. It won East Lothian, not by the slimmest of margins, but with over 3,000 votes to boot against George Kerevan. Elsewhere, the margins were smaller, but Labour managed to pull out wins in Midlothian, Gordon Brown’s old seat of Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath, and more remarkably, in its old Glasgow area heartlands of Coatbridge, Chryston, and Bellshill, Rutherglen and Hamilton West, and Glasgow North East. Oh, and Ian Murray kept his Edinburgh South seat with over 15,000 votes to spare – a remarkable feat which has hardly imaginable throughout the campaign.

As for the Liberal Democrats, they did about as well as they could have with all things considered, for conservative estimates had them winning three seats; they ended up with four and almost won a fifth. Like Labour, they took back old heartlands from the SNP – Edinburgh West, Caithness, Sutherland, and Easter Ross, and East Dunbartonshire – and Alistair Carmichael held Orkney and Shetland with an increased majority from 2015. Back then, when that was their only seat, they had 7.5% of the popular vote in Scotland. It is therefore remarkable that with only 6.8% of the vote this time, the LibDems won more seats, which is a credit to their campaign targeting and concentrating resources in seats they believed were winnable and it paid off.

However, the biggest beneficiaries by far of this election were the Scottish Conservatives. The party which had been completely wiped out in 1997, had only held a solitary seat at Westminster since 2001, been branded as “toxic”, and made into a pariah and the butt of the infamous panda joke had not only returned from oblivion and irrelevance, but emerged as a major player once again on the Scottish political scene and with the potential to shape UK politics as well. Since the start of the campaign, it was thought that the Tories were poised to win new seats in Scotland – perhaps a half-dozen or so in realistic terms and indeed, there had been the concern that a with past proclamations of Scottish Tory revivals and breakthroughs, this would be a dud or at least fall below expectations. This perhaps explains why they astutely managed such expectations and urged a great dose of caution when the exit had the SNP losing 22 seats.

However, the Conservatives went on to have their best general election in Scotland since 1983 when they won 21 seats with Margaret Thatcher at the helm (and when considering vote share, it was their best result since 1979, also with Thatcher). This time, they won 13 seats – far more than what they expected in their wildest dreams. There were the seats they expected to gain in any circumstance – Berwickshire, Roxborough, and Selkirk, Dumfries and Galloway, East Renfrewshire, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine, and Aberdeen South; there were the seats they believed they had a 50:50 chance on a better than expected night – Stirling and Moray; and then there were the seat they considered long-shots and only attainable on an exceptional night – Ochil and South Perthshire, Angus, Ayr, Carrick, and Cumnock, Banff and Buchan, and Gordon. Additionally, they held Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale, and Tweeddale – the seat of Scottish Secretary David Mundell – by nearly 10,000 votes.

In short, the won just about everywhere, but were particularly strong throughout their traditional heartlands in Perthshire, the North East/Aberdeenshire, and the South/Borders – areas where they are once again dominant (with the notable exception of Perth and North Perthshire) and with particular interest to the South/Borders, they represent all of the constituencies in that area for the first time since 1959. Also for the first time since then, the Tories had a greater percentage of the popular vote than Labour thanks to big increases in their vote across the country, with the SNP vote dropping sharply and swinging to them, so that there were Tory gains (in vote percentage if not seats) in places where they had been moribund for decades.

Aside from these superlatives and numbers (which have been astutely written about by blogger Kevin Hague), it is a testament to the strength of the SNP backlash that all three pro-UK parties did as well as they did and significantly outperformed expectations, including my own. Indeed, the breakdown of the results have shown that they could have done even better, because in places where the swing against the SNP was not enough to take the constituency, it was enough to slash dwarfing majorities to the point where several seats were up in the air for much of the night. Of those, there were nine seats won by the SNP by a thousand votes or less, and if they had gone the other way to the second-place candidate, the Conservatives would have added two seats (Perth and North Perthshire and Lanark and Hamilton East) for a total of 15, the Liberal Democrats would have had five with the addition of North East Fife, and Labour would have picked up six more (Inverclyde, Dunfermline and West Fife, Glasgow South West, Glasgow East, Motherwell and Wishaw, and Airdrie and Shotts) for a total of 13 – which would have amounted to 26 SNP seats and a collective 33 seats for the pro-UK parties.

How the political map of Scotland would have looked if the nine most marginal SNP constituencies had voted the other way. Image Credit: BBC; modified by Wesley Hutchins.

For Labour, most of these seats would have come from its old West of Scotland heartlands and the fact that it did come agonizingly close in those places in addition to winning back the seats has been attributed to the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. As was mentioned above, there were people like Loki the rapper who voted for independence and may well still support independence, but were attracted to Labour’s manifesto under Corbyn as well as what they saw as Corbyn’s bona fide socialist credentials. In contrast, the SNP has become seen as too cautious and compromising for the sake of middle class votes, and the result has been that some of the soft “Yes” voters who abandoned Labour two years ago are now at least giving the party a hearing again and voting for it. In other areas of the country, particularly in the North East, the Tories benefited from something of a Brexit bounce in part due to fishing communities and their attitudes toward the EU. In both cases, there was also some fatigue over the SNP being too obsessed about independence to the point that nothing else seemingly matters.

Indeed, it was the issue of another referendum in breaking up Britain which loomed large over this election and the pro-UK parties campaigned to varying degrees opposing such a referendum, so as to make the SNP “get back to its day job” in running the day-to-day functions of the Scottish Government and return to politics not purely centered on constitutional issues. The result was a shellacking at the polls and a 61% pro-Union majority between the three parties which asserted itself and told the Nats: “No, we’ve had enough, thank you.” While the number of seats did not reflect this, the political map of Scotland has nevertheless become more healthy, colorful, and representative of Scotland.

All of this is why even with a majority of Scottish seats at this election, the SNP lacks what they had hoped for: the ability to claim that they are the will and voice of Scotland made in flesh, so that they would have had the moral case and leverage for applying pressure on Westminster for a second referendum. However, it appears that have not got the message, at least not entirely. Nicola Sturgeon has admitted that the possibility of another referendum may have had an impact at this election, but little else.

The problem is that Sturgeon misjudged the voters of Scotland in the wake of the Brexit vote. She expected – as did I, it must be said – that there would be a sharp spike in support for separation with Scotland voting overwhelmingly for the UK to remain in the EU, but the UK as a whole deciding to leave. Within hours of the vote being declared, she announced that a second referendum was “highly likely” so that Scotland could keep its place in the EU while the rest of the UK got out. What ended up happened was that people resented their pro-EU vote being used for naked political opportunism and being taken for granted. The sustained spike in support for separation has not happened and if anything, the signs are that it is going the wrong way, with this election being proof of that.

There is the possibility that this a bump in the road from which the SNP may bounce back – and in these febrile times, don’t count against it – but it could also be something far more and it may well be the Nats have to reckon with the possibility that we are past “Peak SNP” and that the election amounted to something of a market correction. At the least, what has happened suggests that Sturgeon prematurely marched her troops up the mountain and convinced them that all they needed was one more push to get to the top and see a Promised Land which now appears far more distant and less inevitable.

Depending on how Brexit goes, this may change, which is why the new SNP Westminster group leader Ian Blackford is calling a second referendum an insurance policy against Brexit. However, there are many who are seeing right through this, such as Fraser Whyte on Twitter, who said that this was akin to saying: “chopping my leg off is insurance against stubbing my toe”. Indeed, independence and the case for it has become complicated and even less reassuring because of Brexit, especially when one considerers that all of this may lead to Scotland being out of the UK and the EU – a double whammy which few people desire and at any rate, there’s also a recognition that the UK matters vastly more to Scotland than the EU.

The result is that waving the independence issue around in any context has proved a vote loser and is testing the patience of the electorate and the SNP are danger of acting as though nothing has happened and treating this election as a minor blip before regular service resumes in the march to independence. Well, just ask Labour about the “minor blip” they’ve had since losing power at Holyrood in 2007.

However, the pro-UK parties must not become complacent and wait for the SNP to make mistakes and hope to ride to more victories based on them. This election has given them a tremendous boost and the 24 seats between them can serve as the foundation for further growth, but they need to articulate their respective visions for Scotland within the UK and lay down credible alternative policies. This is especially true at Holyrood, where there is a market for fresh ideas after ten years of SNP rule, but also at Westminster, where they can influence policies which affect to whole United Kingdom. Non-party organizations such as Scotland in Union will also play a role in providing a non-partisan outlet for pro-UK activism and have already shown their capacity for making a difference. The tide appears to be turning, but it will be imperative to challenge the SNP head-on on more than just constitutional issues to ensure the Union’s long-term survival.