SOS United States (and QE2)

/Along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, an enormous ship is tied up at a pier upstream from the Walt Whitman Bridge. Her two huge funnels – once brilliantly painted red, white, and blue – have faded significantly without a new coat in over four decades, and her black-and-white hull drips with rust. Her lifeboats and the davits that held them are long gone, and so are virtually all of her interiors. She still has her steam turbines, but they haven’t been used to drive her since 1969.

She has been there for nearly 20 years, and still to this day, many people drive by her every day and do not know what she is, and for that matter, many other Americans don’t know her either.

The ship I speak of is the SS United States, and she is now only days away from potentially being sold for scrap.

If such a thing were to happen, it should be a national outrage and disgrace, for the United States – affectionately known as the “Big U” – is not just any ship. She was our national flagship and a source of national pride as one of the greatest passenger liners ever built.

She was conceived following the end of World War II, when the US Government was so inspired by the troop-carrying abilities of the British luxury liners Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth that it decided to sponsor the construction an American merchant vessel that could also carry 15,000+ troops if ever there was a need, and with the Cold War in progress, it seemed as though this was a possibility. Under the auspices of the administration of President Harry S. Truman, the US Navy underwrote $50 million of the $78 million construction cost, with her owner, the United States Lines, kicking in the remainding $28 million.

Queen Mary arriving in New York carrying thousands of serviceman home following the end of World War II. To this day, she retains the record for the most souls ever carried aboard a single vessel: 16,683 (including crew) on a crossing from New York to Greenock in July 1943. (Credit: Public Domain)

The new vessel was designed by William Francis Gibbs, America’s foremost naval architect, and was built by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Virginia. With her second role as a troop carrier or hospital ship in mind, she was designed to Navy specifications – which included heavy compartmentalization and having two sets of engine rooms, piping, and electrical systems, as well as the ability to carry enough fuel and stores to last 10,000 nautical miles.

Unusually for a passenger vessel at this time, the United States contained virtually no wood aboard her. Interior fittings and fixtures – including chairs, tables, beds, and other furniture – were made from metals, glass, and other fire-proof materials. Fabrics were manufactured with spun glass fiber, and even the clothes hangers were made from aluminum. This had as much to do with William Gibbs’ obsession with fireproofing as it did with the Navy specifications. He even tried to get Steinway & Sons to build a special aluminum grand piano, and was only persuaded to accept one made from a rare fire-resistant wood after the wood was doused with gas and set afire without it igniting. The only other concession was said to be the butcher’s block.

Without the heavy use of wood and with the incorporation of aluminum for the superstructure, the United States was considerably lighter than the British Cunard White Star Queens, and was also designed to fit through the Panama Canal. Nevertheless, at 990 feet long and with a gross tonnage of 53,300 tons, she was (and is still) the largest ocean liner to have been built in America.

She was also built for speed, and was fitted with Westinghouse steam turbines which were designed for aircraft carriers. They were largest steam turbines ever taken to sea aboard a merchant vessel, and could develop up to a whopping 240,000 shaft horsepower for her four propellers. This, combined with the relative lightness of the vessel and her hull design, allowed the United States to cross the Atlantic in just over three days on her maiden voyage in 1952 and beat the Queen Mary’s fastest time from 1938 by ten hours with an average speed of 35.59 knots. She was capable of steaming astern at 20 knots, and could go as high as 38 knots (44 MPH) in forward direction (though this was kept under the wraps of Cold War secrecy for decades). In regular passenger service, she typically sailed at around 30 knots like the Queens to make four-day crossings from New York to Southampton and back. To this day, she is still the fastest passenger liner in the world, and holds the Blue Riband for the fastest speed on a westbound voyage (and was the first American ship to do so in a century).

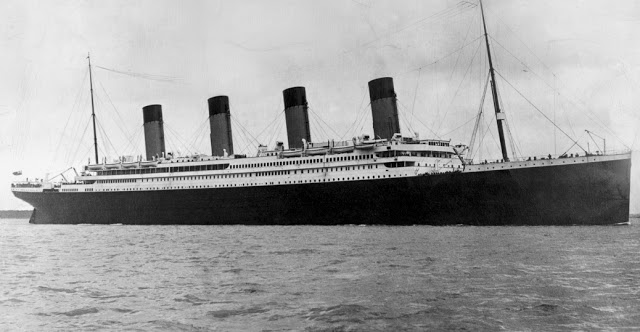

SS United States in her Heyday on the North Atlantic Run. (Public Domain)

Throughout her 17 year career, she was fortunately never used for wartime service, though she was placed on standby during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Instead, she sailed the seas carrying thousands of fare-paying passengers in peacetime. Despite the lack of wood, creative designs using the fireproof material produced fabulous interiors which rivaled those of the liners which carried wood. She soon became a favorite of many on the Atlantic run, including a variety of politicians, celebrities, and other noted people. Among those on her passengers lists were President Truman, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, John Wayne, Duke Ellington, Bob Hope, and Princess Grace of Monaco – to name but only a few. She also carried a young Bill Clinton to the UK for his Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford.

However, like many other vessels, the Big U fell victim to the advent of even faster and cheaper air travel, and she was abruptly withdrawn from service in November 1969 to be laid up in Norfolk, Virginia. Nine years later, the US Navy no longer considered her useful for their needs as a reserve ship, which opened the door for her to be sold. Since then and through 2009, she passed through several owners – all of them with plans to resuscitate the ship for sea travel – all of which fell though for one reason or another.

In 2011, ownership was passed to the SS United States Conservancy, whose chairperson is Susan Gibbs, granddaughter of the designer, and whose executive director is Dan McSweeney, son of one of her captains. The conservancy has been trying to raise awareness of the ships plight and attempting to attract developers and other stakeholders, so that the liner may be refurbished and used in a stationary manner. With the interiors mostly removed to remove asbestos in the 1990’s, the United States is an open slate for virtually any development, and her hull – thanks largely to her Navy specified design and construction – is very sound for its age, despite the image given by the faded paint.

Now however, it really does appear that the ship is reaching the end of the line. With docking fees amounting to $60,000/month and with still to no concrete way forward despite all efforts, the Conservancy has announced that if no progress is made through October 31st, it will have no other option but to sell the ship to a “responsible recycler.”

Perhaps this is inevitable. Why, you may ask, should anyone bother themselves over a vessel that is over 50 years old and rusting away? Why should any person or entity pour vast sums of money into something that has served its usefulness and is only cared for by a few enthusiasts?

SS United States moored along the Delaware River in Philadelphia - waiting for her Future. (Credit: The Hartford Guy via Flickr cc)

My response is that the United States, despite its age and derelict appearance, is a national treasure of the United States – much like the USS Constitution, the Wright Brothers’ plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Empire State Building. All of them, like the United States, were engineering marvels in their time and achievements in the realm of science and technology, and also like the United States, symbolized the ideals upon which the country was founded, including that can-do spirit and the belief that we can make great things happen when we put our minds to it.

The Big U arguably stands out more so because she is the last and largest of her kind to be built in America, and there is little prospect of another US-built ocean liner of similar size and capabilities. Being the last of a breed that has already met the scrap heap or been wrecked, a uniquely American technological and engineering triumph, and the national flagship, it would be a sad day indeed for her to meet an ignominious end. Such a destination would likely take her to the shores of India to be broken up.

This sight of such a great vessel bearing the name of our country being broken down bit by bit and reduced to nothing will be unbearable to watch. The thought alone should cause all Americans and our government to take notice, and the Conservancy has been working hard at this 11th hour to get the news out about ship and its meaning to our country and our heritage. The Big U has been repeatedly featured in news programs and talk shows on radio and television in the last three weeks, and special articles in print have been making her case known to the wider public, with mentions of the impending scrap sale and making appeals for donations. There has also been a call for developers to help come up with a real and sustainable plan for her, along with possible help from government agencies. So far, nothing as publicly emerged, and it really looks like the end.

For now however, at least we still have the Big U in the United States. The United Kingdom however, has already lost its one time flagship, the QE2.

RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 was launched on the River Clyde by HM the Queen in 1967, and sailed on her maiden voyage in 1969 – the same year the United States was withdrawn from service. Indeed, she was Cunard’s last-ditch gamble to save it from extinction in the face of the popularity of air travel. Unlike the Big U however, the QE2 sailed the seas for nearly 40 years and was a favorite among many a passenger and ocean liner enthusiast.

As a revolutionary dual transatlantic ocean liner in the summer and cruise ship in the winter, the great Cunarder was able to make money throughout the year, and she enjoyed an illustrious career in which she carried over 2.5 million passengers – from the well-known (including royalty, presidents, prime ministers, diplomats, and celebrities) to people of modest means who would only make one passage aboard QE2 in their lifetime. All were treated to unparalleled and sophisticated luxury aboard a ship that carried the legacy of the great Atlantic liners that had come before her, and she developed a solid reputation for reliability and comfort – setting a standard against which other ships were compared.

RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 on her last visit to the Clyde in 2008. (Credit: Dave Souza via Wikimedia Commons cc)

Along the way, she made 806 transatlantic crossings and sailed 6 million miles. This included the period during which she served her country in the Falkland’s War as a troop transport (just as her predecessors had done in the previous world wars). In addition, she was the longest-serving liner in Cunard’s history, as well as its longest-serving flagship. On top of that, the QE2 was the fastest operating passenger vessel until her retirement.

That retirement came when the QE2 was sold to Dubai World for $100 million and sailed there in November 2008, where she was supposed to be converted into a floating hotel like the Queen Mary in Long Beach, California. However, at the time when QE2 was purchased in 2007, the property boom was at its height, and by the time of her arrival over a year later, the global economy was on a downward trend, and this seriously affected the QE2’s prospects in Dubai. Since then, no conversion work has been done on her, and all long-term plans for use of the ship have fallen through.

Up until two years ago, she was very visible and well-kept at a berth in Dubai with her engines and internal power systems still running as if ready to head back out to sea again. In 2009, she was drydocked and her hull was cleaned and given a fresh coat of paint, which raised prospects of sunny days ahead. However, the engines have been since turned off, and without them, the ship has been left to bake in the desert sun of the Middle East – with mold and mildew now making themselves present. Worse, she has been placed into a rather nondescript area with tankers and cargo ships, and the latest photos show her looking derelict and forlorn – as if she is being deliberately left to rot. Other photos, including those with workers roasting pigs near the swimming pools, have only confirmed the languishing state in which the former flagship of the British merchant fleet finds herself.

Rob Lightbody, the founder The QE2 Story – a website dedicated to preserving the memory of the great vessel and to raising awareness to save it – told The Scotsman: “Nothing has happened to it in the last two and a half years. There’s no power. There’s no air. She’s filthy.”

2009 Photo of the Queen Elizabeth 2 in Dubai (Indigodelta via Wikimedia Commons CC)

Dubai meanwhile have been frustratingly silent on the fate of this much-beloved ship. Having promised to be faithful stewards of the QE2 from the outset – with an ambitious plan for her going forward – they have all but signaled that they are no longer interested in what was once supposed to be the crown jewel of their Palm Jumeriah development. This lack of interest is only ripe for them to want to be rid of what has now become a liability, and by any means if necessary, which obviously means the scrapyard.

As with the United States, the Queen Elizabeth 2 has a community of people who want to save it. In her case, they would like to see her returned to Britain and preserved for future generations. Thankfully, she has not been laid up nearly as long as the Big U and still retains much of her interior and fittings, so the potential cost of refurbishment should be lower than that required for the United States.

Nevertheless, that’s always going to be the sticking point: cost. Renovation and conversion costs for the United States range from $50 million to $200 million, and then there’s another $2 million for poentially moving her to a new location, such as her original home port of New York City. Throw in the annual costs of maintenance, docking fees, and wages and salaries, and you realize why taking in a 63 year old ship is not an enticing prospect for anyone who wishes to make a return on investment, especially in a relatively short period of time. The costs for the QE2 may not be as high with regard to a renovation, but they will definitely be there with regard to getting her back to the UK, and meeting the burdens of annual maintenance, docking fees, etc., which may perhaps make it difficult to just break even.

In this sense, the odds are pretty stacked against these two great ocean liners. Throw in the struggles that the Queen Mary has endured in Long Beach (some of it arguably self-inflicted by the city) through a succession of several operators with different ideas for an even older vessel, and you can see why even those in the ocean liner community are skeptical of efforts to save the Big U and QE2, and are prepared to bow to the “inevitable.”

Stern of the Queen Mary in Long Beach. (Sergey Yarmolyuk via Wikimedia Commons cc)

However, ask this: what does it say about us when are unable or unwilling to lift a finger to save critical elements of our national heritage in the US and the UK? What does it say about a society that turns their backs on something that has represented that best of their country, and is a critical part of national identity and purpose? What does it say about a people who cannot see that something so unique and special is going to be lost forever? What does it say about us that we just don’t seem to care?

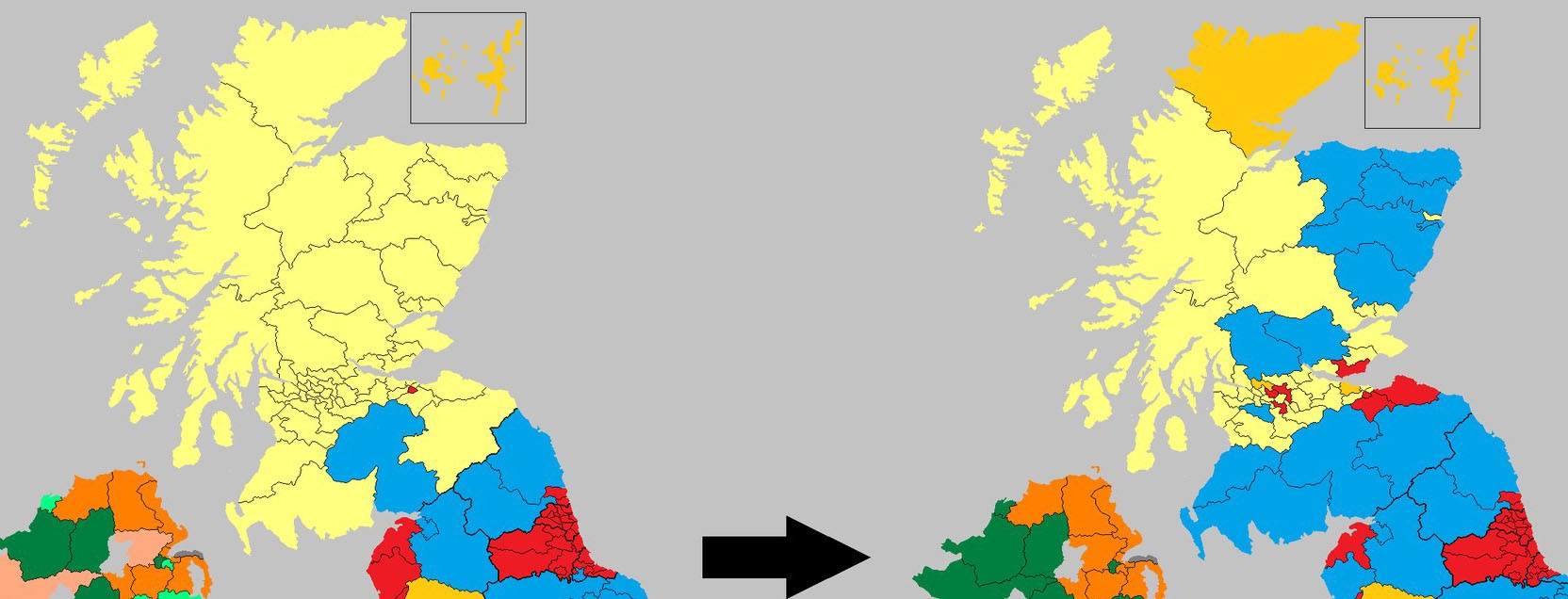

The United States and the Queen Elizabeth 2 can be saved if we really want them to be saved. They can be rehabilitated for new and appropriate uses if we really want it to be so, and much more could be done by public and private interests, again, if people demanded it to be so. The problem is that there is not an outcry – either from Maine to Hawaii, for Shetland to Cornwall – for the government and/or those with deep pockets to do something helpful and constructive with regard to these liners for the benefit of the nation and future generations of Americans, Britons, and the world at large.

Some people will say that as unfortunate as it may be, it is probably time to let them go and be scrapped. After all they say – with justification – that we cannot expect to save all the ocean liners that have ever been built, and the brute reality is that when a ship reaches the end of its intended use of sailing on the high seas, its only realistic destination is the scrap yard. As the last captain of the Queen Mary said upon the great liner departing New York for the last time in 1967: “Ships, like [human beings], have a time limit, and they day must come when we go.”

However and again, I must stress that the Queen Elizabeth 2 and the United States are different, and ought to be exceptions to the rule. They represented the best of their respective countries to the world with a standard of luxury, comfort, style, and class that made them stand out amongst their contemporaries. Above all that, they are well and truly the last of their kind, and indeed, the last of an era. In addition, being the last great liners built in Britain and America is, in my estimation, the main feature that makes them special and worth saving, and given their profiles, it would an enormous blow to national prestige and honor to watch them be ignominiously scrapped.

With particular regard to the Big U, I have to believe that if she was meant to be scrapped, she would have been scrapped long ago when the Navy no longer had use for her in 1978. She was not broken up, and has made it this far, so that I was fortunate to see her about eight years ago while visiting Philly with my father, and I have to say that she appeared to have much potential – with a lot of space that could be put to good use and ensure her survival. It is almost as though we have been given chance after chance to save her and keep her going and now, it just seems that she has come too far to only now face the torch.

As for the QE2, I saw her when my father and I visited New York in 2001, 2002, and 2003. Each time, she was an awesome sight to behold – with her iconic funnel in the traditional Cunard red and black, her long and elegant black hull with a white superstructure, her clipper-shaped bow, and well-rounded stern. Overall, her profile was graceful and neatly-balanced – a great dollop of credit to her design team and the people who built her in Clydebank. She looked so splendid – and even regal – like the Queen that she was, and still is. Underneath the grime, rust, and mildew is the QE2 that we all knew and loved.

My father and I at the New York City Passenger Ship Terminal with the QE2 in 2001. (Wesley Hutchins)

Both she and the Big U need to be saved, not just for their individual attributes, but also for their importance in the rich seafaring traditions of Britain and America, which ought to be celebrated and cherished, especially in Britain because of it being an island nation dependent on overseas trade throughout the world. With their loss, I cannot help but to believe that we will have lost a bit of ourselves and be condemned for allowing it to happen.

For the United States, there needs to be cooperation between the US Government, private entities, individuals, and the governing institutions and agencies of the areas that are willing to berth the ship – whether it be in Philadelphia or New York. Going further, she can be a great national project for the US in terms of breathing new life into her, for again, her interiors are largely gone and the empty spaces are open to creativity, while also respecting her overall dignity. While serving as something useful, she can be a symbol of American ingenuity and what America was able to do at one time, as well as a symbol of what we can do going forward with that same sort of ingenuity.

Time is running out for the Big U, and there is the real possibility that she will be scrapped, which will be nothing less than a tragedy. The most important thing to is speak out and letting relevant authorities know that the ship is paramount to who we are as a country, and therefore worthy of being spared.

Rehabilitating her not be easy, and will require the cooperation and good faith of many people and organizations. But with help from all stakeholders and the wider public, something can be made from this desperate situation. Just it is desired to have the Queen Elizabeth 2 returned home to a more happy and glorious future, hopefully it will be morning again for the United States.