Delusions and Deceit (A.K.A. the SNP's Independence Case)

/Yes vs. No? People noting their support for keeping the Union for going independent. Image Credit: Brian McNeil via Wikimedia Commons cc

Scaremongering.

Fearmongering.

Talking Scotland Down.

These were the emotive buzzwords and phrases used by separatist campaigners during the referendum last year as a defensive answer to the claims of pro-Union campaigners that Scotland would not be better off separated from the United Kingdom as an independent country.

Time and time again, legitimate concerns over currency, central banking, public finances, defense, jobs, and the general economic outlook of an independent Scotland were breezily dismissed as trying to scare Scots into rejecting separation, and met with responses such as:

“Oh, you’re saying we’re too wee, too poor, too stupid?” (Thanks, John Swinney)

“You don’t believe we are capable of running our own country?”

“You would rather have [big, bad] Westminster decide our laws and take our oil, rather than us?” (Blood and soil nationalism?)

Now to be honest, some claims about what would happen were a bit over-the-top, and it did not help when an insider from the official pro-Union campaign organization, Better Together, made an off-the-cuff quip about calling themselves “Project Fear.” This label stuck and was used as a means to discredit Better Together and any other entities, groups, and individuals in support of keeping the United Kingdom together.

Arguments meant for highlighting the strengths of the UK overall as a country and in relation to Scotland were misconstrued to accuse those supporting the Union of having no faith in Scotland or not believing in Scotland “taking charge of its destiny”, as was illustrated by the white paper which was released in November 2013, and laid out the SNP’s case for independence. Entitled Scotland’s Future: Your Guide to an Independent Scotland, it was published by the Scottish Government (and paid for by the taxpayers), presented as the prospectus for an independent Scotland, and billed by then-First Minister Alex Salmond as the “most comprehensive blueprint for an independent country ever published.”

If fact, it was more like an election manifesto with a wish list of political objectives, rather than a constitutional framework – promising a land of milk and honey built (to a great extent) on oil prices at $110+/barrel, and keeping the currency (and other assets) of what remained of the very country that would have been broken up with a vote for separation.

The White Paper became a Bible for separatist campaigners and any efforts to question its assertions were met with derision, condescension, and accusations of lying and stoking fear. Even after voters saw through the dodgy claims and chose to maintain the Union, the charge that Scots were “too feart” and scared by Better Together, the BBC, the UK Government, J.K. Rowling, Barack Obama, and others has persisted as a means of shutting down debate and to nurse grievances, while also agitating for another referendum (which some of the more hard-line folks believe is just around the corner and that they will win it).

Not so fast, says Alex Bell – former head of policy for the SNP and right-hand man of Alex Salmond. From 2010 through 2013, Bell was tasked with coming up with a plan for an independent Scotland and was therefore had a significant hand in the development of the White Paper, and by extension, the model for independence which was the basis on which the SNP and others campaigned, which garnered nearly 45% of the vote on Referendum Day.

However, in a bombshell post this week on the website (appropriately named) Rattle.scot, Bell not only dismisses that model as “wishful” for the campaign last year, but declares it to be “broken beyond repair” and accuses the SNP leadership of being unable to find a way of “safely” achieving their foremost aim.

He argued that all things being equal – and without regard for emotive rhetoric – the referendum for most people came down to how people felt about the short-to-medium term economic health of Scotland post-independence, with its effects on the ability of the government to spend and borrow. If people believed that Scotland could afford its way as an independent country and maintain current levels of public spending without resorting to taking on a lot of debt and/or substantially raising taxes, then they would at least be more receptive to the SNP’s vision.

Indeed, the party’s modern success arguably started with the “It’s Scotland’s Oil” campaign in the 1970’s, and partly built on the idea that revenues from North Sea oil in British waters (mostly off the coast of Scotland) resulted in Scotland paying more into the UK Treasury than it got back. The reasoning therefore was that if Scotland kept the lion’s share of the revenues for itself as an independent country, it would rank as one of the wealthiest countries in the world in its own right and be able to maintain British levels of public spending.

The problem, as so many people pointed out during the campaign, was that this was flawed logic because of the fact of there being a gap between revenue raised in Scotland and the amount of public spending in Scotland – with the gap being filled in via the block grant allocation that Scotland receives by virtue of being part of the United Kingdom. Not only that, but while Scotland may have contributed more per head than got back in part because of the oil, it also received more per head than the UK average in terms of public spending.

For this reason alone, Bells says, the SNP’s model for independence was broken because it was not “possible to move from the UK to an independent Scotland and keep services at the same level, without either borrowing a lot more or raising taxes”, and if not those options, then services would have to be cut in order to bridge the gap. All of these options are unpalatable to the majority of voters and all come with costs associated with becoming independent.

If it wanted to go down the borrowing route, an independent Scottish Government would face higher borrowing costs as a new state – making its anti-austerity agenda expensive by adding costly debt onto its already costly share of the UK’s debt. But Scotland being part of a currency union – either using the pound or the euro – would limit its ability to borrow anyway, as would the creation of a new currency which “may not be trusted by lenders.” Without the capacity to borrow freely, taxes would have to go up, but then that may not be enough to cover the cost of becoming independent, and Bell pointed to the troubles with regard to the merger of Scotland’s eight regional police forces into a single one and implored readers to multiply this a hundred times over in order to get a sense of how much separation really costs.

It was therefore ludicrous for the SNP to make all the promises it made to the people of Scotland in the White Paper and throughout the campaign because in there was no “thorough, independent understanding of those additional charges” of separation which would have affected the ability to deliver those promises after the fact. Such obstacles could be overcome, claims Bell, but he also remarked that it would be “stupid to deny they exist.”

The problem was that the SNP and various other independence campaigners appeared to pretend that these obstacles did not exist, and instead went down the road of talking up the possibilities that would come with independence, without Westminster and the dastardly Tories getting in the way. In short, these concerns were "obscured by lots of noise, and the SNP is accomplished at shouting."

But according to Bell, it appears that even the higher echelons of the SNP knew that their vision for Scotland did not add up. He claims that a paper – seen by few and probably destroyed – was written by civil service officials in 2012 presenting the idea of ‘independence in the UK’ and basically argued that “the SNP’s case – UK levels of spending, no tax increases, relatively high government borrowing but a stable economy – was more possible within the Union than without.”

He went on to say that this future for Scotland now seems more likely, and that Finance Minister John Swinney – lest he be unfit for his job – should understand this especially in light of “declining oil revenues and a long period of low growth.” Whatever else the party may say from current First Minister Nicola Sturgeon on down, Bell warns that the brute reality is that:

“The idea that you could have a Scotland with high public spending, low taxes, a stable economy and reasonable government debt was wishful a year ago – now it is deluded.”

This was particularly devastating, and combined with the other revelations and unvarnished views, they are akin to a semi-Road to Damascus moment for a person so intimately involved in the process of drafting the document used to argue the official line on why Scotland should be independent. It's as though he no longer believes in it (and judging from his post, you wonder if he believed in it all), and for those who had expressed the same shortcomings, this is an act if validation, for they knew the claims and sums did not add up. Based on the most optimistic of assumptions, the White Paper presented a case for separation which rested on flimsy grounds and constituted an act of deceit and political malpractice, which would have had adverse consequences if separation has won out, especially on the working classes.

Indeed, Bell's statements could have been lifted right from similar statements made by Alistair Darling, Gordon Brown, Ruth Davidson, and almost any pro-Union campaigners who saw the White Paper for what it was: a manifesto of pledges which the SNP could not deliver on upon independence. The collapse in oil prices alone have shown that SNP could not promise their vision of independence based on prices at $110+/barrel any more than Labour could promise that it would form the next UK Government following the general election this year.

The Bell revelations show how false the SNP’s prospectus was, how close Scotland – indeed all of Britain – came to the brink, and how the people were right to keep the Union together.

Unfortunately, the time during which this revelation would have inflicted serious political damage has passed and likely will not cause as much as a dent in the SNP’s poll numbers. The party has become so dominant, that it seems almost blasphemy to question the conventional wisdom that they will win an unprecedented third term in government and another majority at Holyrood.

However, this sense of inevitability breeds arrogance and complacency, and nowhere was this shown more blatantly than SNP MP Pete Wishart (referred to by the Daily Record as “everyone’s favourite whiner”) who wrote in his personal blog about pro-Union parties criticizing his party for its record on health, education, and policing going into the Scottish Parliament election next year.

According to the MP for Perth and North Perthshire, this strategy of focusing on public services and the SNP’s stewardship of them will not work, because “they have not counted on the real experience of real Scots and their trust in us to manage the services they enjoy.” He further cited a poll which showed that only fewer than 30% of Scots viewed the Scottish Government’s management on education, the economy, and health as “bad” while more people believed its management was “good” in those areas. Only in policing were there more people who thought that the government was doing badly, but then, not by much.

Furthermore, not only did Scots apparently think so favorably of his party, but he also dismissed the notion that the other parties could offer up an credible alternative plan for government that the people would vote for. Not only this, but the poll also showed that 62% of Scots were planning on voting for the SNP next year, with Labour and the Conservatives in the teens and twenties, and the Liberal Democrats at single digits. From this vantage point, Wishart accuses them of “talking down” Scotland’s public services in a “forlorn and ultimately self-defeating” bid to attack the SNP’s record on those services and recover themselves north of the Tweed.

Reading this, you would be forgiven to believe that Wishart is laughing at the notion that his party’s record in government should ever be questioned, as though it is iron-clad and impervious to scrutiny. The people trust us, he says, and the unionists have nothing to use against us; no matter how much they (or anybody else) points out our shortcomings, they are headed to defeat. Bring it on, #HR2016.

First Minister Sturgeon herself got into this sort of behavior in a big way during a recent exchange at First Minister’s Question’s at Holyrood, where she raged with indignation against Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale for having the audacity to make criticisms of the SNP’s handling of public services, saying (with probably a flair for the dramatic):

“It’s her miserable approach that denies anything good about this country that sees her and her party languishing.”

Indeed, when they aren’t accusing others of “talking Scotland down”, SNP politicians and activists (especially on Twitter) deflect legitimate criticism of their party and its record by gleefully point out that they are topping the polls, with very little chance for the pro-Union parties – Labour in particular – to catch up to at least a respectable position. They bleat on about how they’re going to win next year, and how there’s nothing to be done about it.

Again, it cannot be denied that the SNP is currently riding high in the polls, but is it possible that the SNP is “maxing out” its vote? On average for the past few months, it has been in the mid-to-upper 50’s in the constituency vote, while it sits around the high 40’s and low 50’s in the regional list (proportional) vote, and has not gone much higher. If there is no more room to grow and we have reached “peak SNP”, then the likely only one direction from here, and it isn’t up.

So, the SNP is going more to hold its broad church coalition, so says Alex Massie, who argues that punting decisions on though issues such as fracking beyond the election is about keeping the current converts happy. In similar fashion, “the Scottish government’s ban on the cultivation of GM crops was taken on the basis of political expediency rather than scientific credibility.” In addition, Sturgeon is apparently mulling over whether to support airstrikes against Daesh (which is something that has the potential to divide the party).

The problem of course is that so often, the party interest is placed above the public interest (and/or common sense), and if this continues, it will contribute to what Massie refers to as the “market correction” that cannot be forever delayed – especially if independence is not forthcoming. Indeed, stripped away of its constitutional obsessions, the SNP would be judged solely by its record of eight years (rather than on airy visions of independence in the distant future or the fights it likes picking with big, bad Westminster).

In this light, Massie points out that the style-over-substance SNP does have questions to answer with regard to its “ministerial priorities” on education – where poor children still perform below standard, on policing – where the operational issues and breakdowns of Police Scotland have been noted, and on health – where spending in Scotland has barely increased compared to England. On all of these issues, for every positive light the SNP likes to show, there more than a few gray areas and dark corners.

In fact, that poll which Pete Wishart cited in his blog post was a TNS poll from August, and while it is true that it showed less than 30% of Scots giving the (SNP) Scottish Government bad ratings on each of the four issues presented, it also showed that only a quarter to a third of Scots rated it good on those issues: crime and justice (23%), the economy (25%), education (30%), and the health (34%). In fact, the biggest number of respondents said that the government was managing those issues neither good or bad, which means that despite the high ratings for the SNP, voters were less than enthusiastic about its performance.

What these numbers likely show is that the voters may be giving the SNP in the benefit of the doubt, particularly in the absence of what they believe to be a credible alternative to the SNP. On top of that – as Fraser Whyte points out in his blog – were the number of undecided voters, all of which means that the SNP will be vulnerable if another party does offer a credible alternative, and while that appears to be in the offing and while there are some voters probably not even tuned in to other parties, this can always change. The past year or so in British (and American) politics have shown that what is perceived to be conventional wisdom can turn on a dime within a relatively short period. If it isn’t careful, the SNP may well be seen as the establishment party that has been in government for too long (and stoking up constitutional grievances), and must be replaced by another party offering better options.

This brings us back to Alex Bell’s stinging criticism, which included the charge that the SNP was becoming less a party of independence and more like the “Scotland party” in the United Kingdom, “while pretending it is still fighting for independence to keep the party together.” The post-referendum debate on independence, he argues, has “gone deathly quiet” as the SNP has co-opted many of the various other forces that fought for independence – though not under the SNP banner and not in accordance to the SNP’s vision of independence – and whipped them into toeing the party line. In doing this to regain control of its raison d’être, the SNP snapped up almost every Scottish seat in the UK House of Commons last May, but also effectively choked off internal debate about independence and the range of possibilities that may come with it.

On top of this, the Scottish Government itself “makes a virtue of saying it is putting no effort into researching independence” – with the SNP resisting things it once wanted, such as an “independent economic forecasting unit” and academic institutions looking into the tax base. Indeed, this is seen with the SNP’s attitude toward an independent study into the full fiscal autonomy (FFA), as well as its less-than-enthused release of this year’s oil bulletin (which was something it was all too often glad to do when oil prices were much higher).

This, argues Bell, shows a party that is “incompetent on its core policy” and admitting failure while being rewarded for it. Without “facts and planning” for separation, the cause will not move forward because the “SNP’s ill-prepared version of independence does not plausibly offer any real alternative” and the party fears internal ruptures may result from facts that become known about what separation may entail, because for some people, it may well be that such facts may lead them to diverge from the SNP’s stated vision or abandon the cause altogether.

The result is that for all the hype about a Scotland that has been changed forever, the reality is that it is “back in the past, dominated by one party, bereft of intelligent debate, doing quiet deals to get by – in short, back to normal.” The party of independence now cares more for its existence than the issue it has run on for over eight decades, and without a credible alternative which features independence as the solution, it may well end up “ultimately settling for a better deal than before” within the UK.

Going forward, this means that an increasingly less-risky SNP may well look back on 2014 as the “sweet spot” year for their separatist campaign – the period when their claims for independence were as aligned as much as possible with the realities on the ground. Without a new model, it is left trying to wait on a convincing shift in opinion polls which may never come, defending the claims of the old model, and finding itself at the mercy of voters for how it performs on those all-important health, policing, and education issues.

This isn’t to say that the concept of independence will die, but the deceit and delusions revealed within the White Paper and the SNP's rhetoric via Alex Bell's confessional are unforgivable, and give people reason to pause. If they don’t believe separation is a realistic alternative or does not excite much interest, they may go down the road of the Quebecers in Canada and eventually chuck out the party that wants separation. Charges of scaremongering and the like may not work so well in the future.

Hope over fear, yes, but also honesty before deceit, especially on a matter such as this.

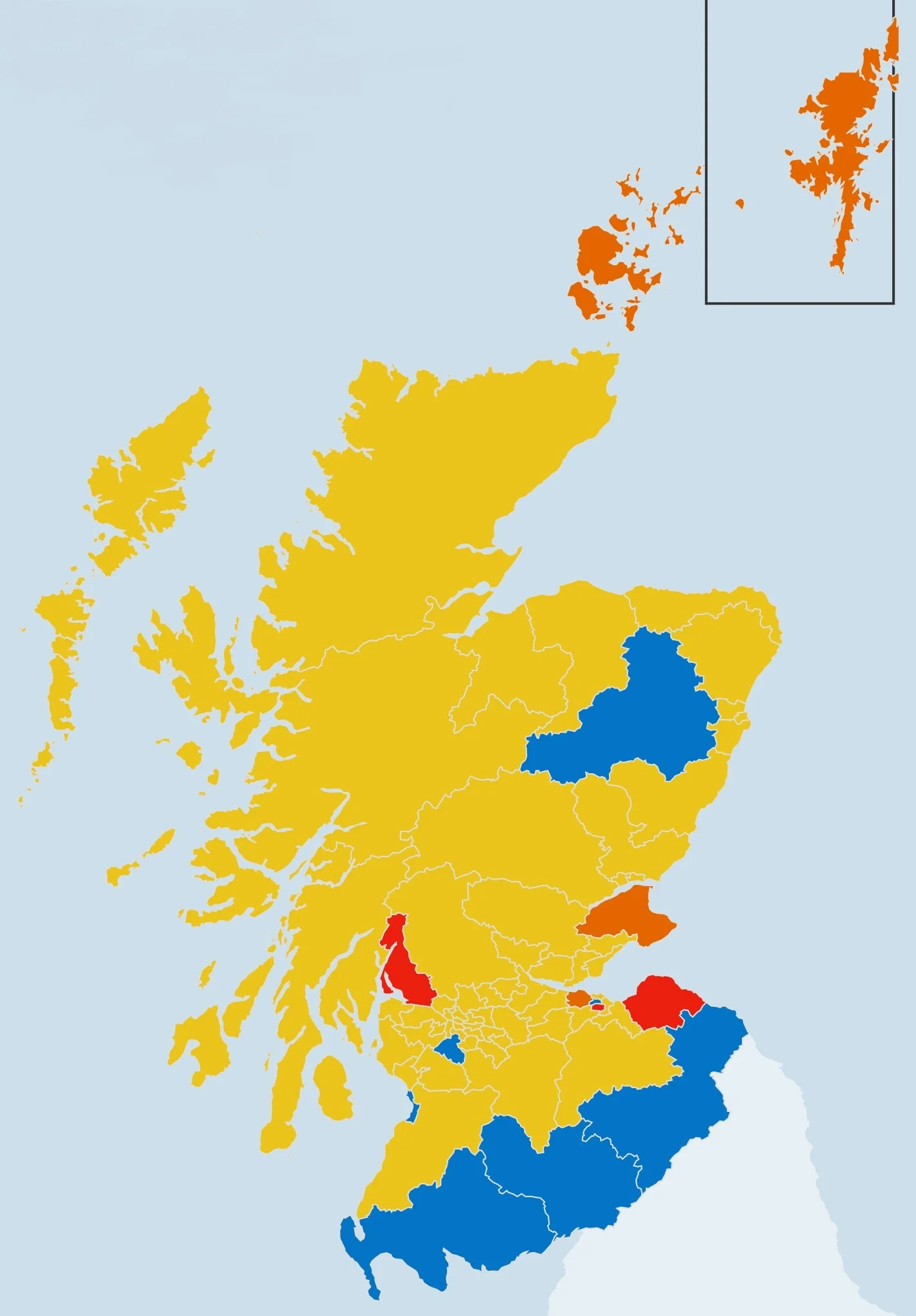

UPDATE: The latest poll from Ipsos-Mori (taken November 9th-16th) has shown a significant decline in SNP support and a rise for the Tories compared to its last poll, as well as the aforementioned TNS poll. It would still mean that the SNP would end up with 72 seats next year, followed up by Labour's 25, the Tories' 17, the LibDems at seven, and the Greens with eight. It's only one poll, so caveats apply for the fact that it may be an outlier. However, it may show that the upcoming election may not be so inevitable.