Fit for Government or Grievance?

/NIcola Sturgeon has gotten by on sheer personal popularity and shaking her fist at Westminster, but How Long Can That LAST? Image Credit: Ninian Reid via Flickr cc

Throughout much of its history, the SNP has made much use of grievance politics – claiming that Scotland is held back by being in the UK, and in particular, by the UK Parliament at Westminster. Even after devolution and being in government, the party has continued down this path of blaming big, bad Westminster for Scotland’s problems, and using this as a reason for Scotland to secede from the UK.

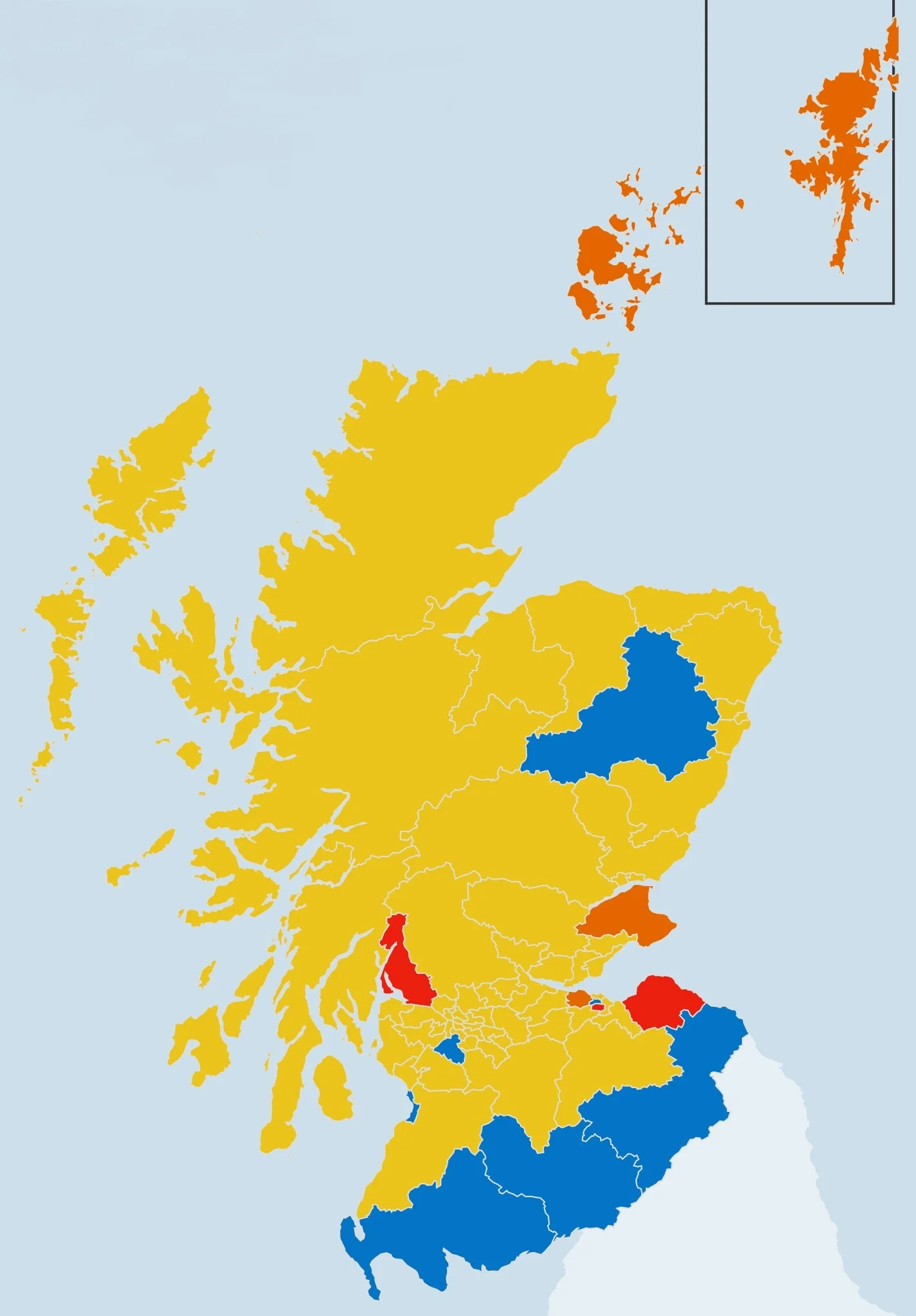

Trumped-up and manufactured grievances were a big part of their campaign to break up Britain last year, and though they failed, they have continued to use this tactic to stoke resentment against the Union and the political parties that support it. This resulted in their electoral landslide at the UK general election, and without fail, they intend on doing it again going into the election next year for the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, where they are expected to win another outright majority and an unprecedented third term.

However, grievances take can take you only but so far in anything, let alone politics, and especially when responsibilities lay at your feet and people demand to know what you are going to do, with an expectation that real action will be taken.

For the SNP, this has become increasingly true as Holyrood gets beefed up with extensive new powers under the Scotland Bill going through its final legislative stages at Westminster, and in the course of this week, the party – having been in government for eight years – showed signs of being a bit off message with regard to tax credits.

The main issue at hand was whether the new devolved powers contained within the Scotland Bill would allow Holyood to top-up tax credits in Scotland following them being cut throughout the UK under proposals by Chancellor George Osborne, which ran into a stumbling block last week in the House of Lords.

Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale announced at her party’s conference last weekend that if elected into government, she would use new Holyrood powers over taxation to retain the current rates paid by top earners (and not going along with planned tax cuts by the Conservatives at Westminster), as well as keep (soon-to-be devolved) air passenger duty as is and not going along with SNP proposals to cut and eventually abolish it in Scotland. Together, these proposals are expected to free up £355 million to restore the tax credits.

But the SNP’s Social Justice Secretary Alex Neil claimed that Holyrood would not be able to restore the tax credits and on that basis, the SNP MSP’s voted to reject a Labour motion to have them restored, and instead pushed through a motion that claimed that Holyrood would not have the power to reverse the tax credits unless they were devolved.

However, the Scottish Parliament's own information service (SPICE) states that with devolution through the Scotland Bill, the Scottish Government will be able to "provide a permanent top-up to a reserved benefit" such as Working Tax Credits. This means that even though tax credits are a reserved policy with the UK Government, the Scottish Government can use devolved powers to restore any tax credits lost to Scottish residents if they are cut by UK Government.

This had already been confirmed by Scottish Secretary David Mundell, and after repeated statements by the Scottish Government that it could not top up credits - including a press release by Alex Neil just hours earlier to that effect and demanding that credits be devolved - Neil admitted that the government could indeed do so during a rancorous debate at Holyrood.

In a further sign of the SNP's confusion on the issue, this was the same rancorous debate at which SNP MSP's rejected Labour's motion to restore the credits and claimed that the Scottish Government could do nothing about the issue.

Speaking on this rather embarrassing U-turn, Labour's public services spokesperson Jackie Ballie lambasted Neil for putting on a "pantomime dame performance" in his defense of the SNP's opposition to Labour's motion, as well as for his apparent waffling and/or incoherence on the issue. She also accused the SNP government of putting "grudge and grievance" above action to help those affected by tax credit cuts, and devastatingly turned a common SNP talking point against it by asking: "Why can't the SNP just embrace the new powers instead of always talking Scotland down? "

Neil responded by claiming that Labour had "no credibility" on opposing Conservative welfare reforms, and that the SNP would continue to seek a full reversal of the proposed tax credit changes at Westminster. To this end, he further stated that the Scottish Government would wait for the announcement of the final tax credit proposals and George Osborne's autumn statement before considering what "corrective action needs to be taken on tax credits, when such action should be taken, how it shall be funded, and how it will be administered."

Sure enough, at First Minister's Questions the next day, Nicola Sturgeon said that her government would present "credible, deliverable and affordable plans to protect low-income households" from the cuts and dismissed Labour's plan as "back of a fag packet proposals", though offered nothing in the way of specifics regarding the SNP's plans.

In his analysis, the BBC's Brian Taylor said that aside from needing to know about the autumn statement and tax credit proposals, Scottish Government ministers - especially Finance Minister John Swinney - were also waiting to understand what kind of fiscal framework they would be working with under the new devolution arrangements (and the full scope of the new powers) before making "costly commitments."

This is actually a sensible policy, so that public money is spent wisely and effectively. Then again, for a party that claims to be for bold, radical action, and being "stronger for Scotland", this apparent reluctance to set out proposals to deal with the tax credit issue may well represent that whatever else the SNP stands for, their main and overriding objective above all else is secession.

To this end, almost nothing can be done by the SNP without it being figured into the greater context of advancing the independence cause. Former Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill admitted as much when he explained why he blocked the extension of voting rights to prisoners last year, despite supporting the idea. It was he said, "the wrong thing done, albeit for the right reasons", and for MacAskill, the right reasons were to "avoid any needless distractions in the run-up to the [independence] referendum, to deny the right-wing press lurid headlines that could tarnish the bigger picture."

In the context of the tax credits debate, if the SNP were truly a party committed to social justice first and foremost, it would not have turned down a motion to support having the tax credits restored via the powers it will soon have at its disposal. But it did to that and then claimed that they didn't have the power to top-up any credits reduced by the UK Government, before having to admit that it did.

The reason why it did this of course, was so that it could pick another fight with Westminster over constitutional process and powers, and to continue their narrative about Scotland being the helpless, defenseless victim of the Union - always being flogged senseless and mercilessly by Westminster and belonging to a hopeless constitutional structure that does not work for Scotland and the Scottish people.

God forbid it if the SNP actually used the powers that are - and soon will be - at its disposal as a party of government to help people, because then it would demonstrate that the constitutional arrangements of the United Kingdom do work for Scotland. If that were to happen, it would blow a massive hole into their argument for independence, and indeed, I remember reading a Herald (or Sunday Herald) article in 2013 which argued that if anything, the SNP's participation in devolved government may have blunted the case for independence because the party was seen as competent in running Holyrood and standing up for Scotland's interests within the safety and security of the Union.

So the SNP cannot allow such thinking to marinate in the minds of the people of Scotland. This is why they have to almost continuously pick fights over the constitution and keep the constitutional debates going - stoking up manufactured grievances and resentment - so that the very idea of independence remains in people's minds and continue to blame Westminster for all of Scotland's problems and demand still more powers, because after all in their eyes, it does not go far enough.

Well, of course it does not go far enough for them, because they wanted a "devo-max" arraignment which would have been independence in all but name (though still relying on the pooling and sharing mechanisms within the UK). On top of that, their all-consuming goal remains full and complete separation, which the voters rejected last year, though this has not stopped them from complaining about the supposed "inadequacies" of the Scotland Bill. As the Daily Record said in an editorial this week:

"Moan, moan, bitch, bitch, whinge, whinge. Their response [to the Scotland Bill] has been as negative as it was predictable. A cynic might argue that the SNP don’t actually want those new powers because it makes them more accountable to the people of Scotland."

Herein lies another reason why the SNP would rather argue over process and powers, because with more powers comes more responsibility and accountability, as well as potential pitfalls for the SNP. With regard to tax credits for example, there is the possibility that they may have to raise (soon-to-be-devolved) income taxes on higher earners and/or hike up other taxes and duties usually paid by the more well-off in order to finance top-ups of welfare benefits.

Throughout the referendum campaign, one of the many refrains from pro-independence campaigners and writers was that Scotland was a more egalitarian society from that in England, and unlike the English, Scots were more amenable to paying more taxes to help the well off. However, almost all polls and surveys have shown that Scots are not much more interested in having their taxes raised than the English, and the SNP knows this. After all, a big part of their success has been to capture "Middle Scotland" with initiatives such as free tuition, free perscriptions, and the council tax freeze - all of which disproportionately benefit the better off - without having to worry about paying for it out of Holyrood.

Despite the rhetoric of social justice, the SNP knows that in order to win anything, you must win the middle ground of the electorate, and heaven forbid if they decide to take away those gifts to the middle and upper classes or raise their taxes to pay for topping up tax credits (in other words - talk left, walk right). After a while, people may see them as any ordinary political party that needs to be replaced by another at some point in the near future, and worse, the cause of secession will stagnate and fall by the wayside.

Against this have been the charge that big, bad Westminster is setting up a fiscal "trap" for the SNP by forcing them to raise taxes to pay for the initiatives they want funded. This is nonsense, for the only reason this is a "trap" is because it will force the SNP to make choices that will be politically unpopular and cost it support from one group or another within its broad church of socialists, neo-liberals, progressives, environmentalists, fossil fuel promoters, free-marketers, social democrats, and hard-core nationalists. Perhaps the "wait and see" strategy is at least partly about coming up with a plan that somehow keeps all of these factions onside and keep the secessionist movement going.

This is why the SNP is not fit for government, for every decision and policy is thought in terms of not what's best for Scotland, but what's best for "The Cause", and if what may be best for Scotland conflicts with what's best for the The Cause, what do you think is going to win out? As MacAskill said, wrong decisions can be made and justified for the sake of independence.

This is why the tax credits issue and the issues surrounding other devolved powers of a beefed-up Holyrood may become a big issue going into the 2016 Scottish Parliament election. This presents an opportunity for all pro-Union parties to set out their respective stalls and present the SNP as the party that's so obsessed with independence and getting powers, as opposed to actually using them for the benefit of Scotland and its people.

For the Labour Party in particular, they can use this in an attempt to reclaim the mantle of acting in the interests of social justice and ordinary working families. Kezia Dugdale and her party were given credit by Iain Macwhirter for “reframing” the tax credit debate and forcing the SNP's U-turn, while Jackie Ballie did well in her sparring match against Alex Neil when she said that the "tax credit debate exposed what really matters to the SNP government – constitutional grievance rather than helping working families in Scotland." Kenny Farquharson of The Times said simply in a tweet: "SNP wants to have powers, Labour wants to use powers."

First Minister Sturgeon sneers at such a prospect - the idea of Scottish Labour being in power, and partly dismissed their tax credit plans on the basis that they came "from a party that knows it has little chance of ever being in a position to implement them."

If I were advising Scottish Labour, I'd place that quote around party offices and remember it well as motivation going into next year's elections. Right now, it seems very unlikely that the SNP will be dislodged from government, but as we have seen in the last couple of years, anything can happen in politics within even the shortest space of time - especially in the current febrile atmosphere, and Labour - along with the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats - ought to treat this election as though there is all to play for.

Indeed however, there is much to play for in the upcoming election. It will decide if Scotland will have a government dedicated first and foremost to using its powers for the benefit of the people (and especially the most vulnerable in society), or if it will continue having a grievance machine that puts constitutional questions before everything else. The people must think hard and choose wisely.