Pragmatism, Taxes, and the SNP

/Last week, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced that going into the Scottish Parliament election in six weeks, her party would maintain the 45% top rate of income tax for the highest earners in Scotland once Holyrood has full control of tax rates and bands during the course of the next parliament. This marks a reversal by the SNP leader, who had argued for restoring the 50% rate at the UK general election last year in the name of raising additional revenue for public services and education.

The reasoning for abandoning the policy was that it would not raise much revenue and cause tax competition that could see high earners earner more than £150,000 leave Scotland or relocate their address in the rest of the UK – thereby not paying any income tax in Scotland at all once full devolution comes about.

If this sounds similar, it is because it the same reasoning that Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne used to reduce the top rate from 50% to 45% throughout the UK in the belief that some investors and entrepreneurs already in the UK would leave for a lower-tax country, and thereby not paying any income in the UK altogether.

Now, regardless of your views on tax policy and the merits of taxing people according their ability to pay, the reality is that most people don’t like paying taxes and when they do, they would rather not pay more – even if they tell opinion polls that they do, and this applies to Scotland just as everywhere else. This is why the SNP is reluctant to raise taxes on anybody, not least the middle and upper classes who have helped the party rise to prominence in the last decade.

But for many of the more recent SNP voters – many of them working class former Labour voters in Glasgow, Dundee, Dumbartonshire, and Lanarkshire – they believed that the SNP was supposed to be a more radical, progressive, and bold party than the party they had left. It was not merely that they had been disappointed with the party standing “shoulder-to-shoulder” with the Conservatives to save the Union, but it was the discontented feeling that the party had taken them for granted for some time and were seen as drifting to the right and away from their socialist political principles in the pursuit of power at Westminster.

New MP’s such as Mhairi Black defeated Labour heavyweights such as Douglas Alexander at the general election last year on the wave of this discontent, and with the message that Labour had left them, not the other way around. They made speeches filled with platitudes about fairer and more progressive taxation, and standing for left-wing principles – and in this regard, Black cited one of Labour’s left wing stalwarts, Tony Benn, as one of her political hero’s.

However, the problem with Benn was that many of his cherished principles were not widely shared by voters throughout the United Kingdom, at least not at the ballot box, which explains why Labour lost with its infamous “suicide note” in 1983 and found that it had to moderate in order to be in sync with the center ground of British politics. Today, the SNP is doing the same with regard to Scotland in particular, and this means chucking away the 50% top rate in order to stay in power at Holyrood.

To be clear, this article is not advocating anything on either side of the tax debate, but is merely pointing out that many ex-Labour voters found a new home in a party they believed was chock full of social justice warriors, and would be bold and do things differently than the other parties, like hiking taxes on the well off and getting away from the “austerity agenda” of Westminster. Now alongside dropping the 50% top rate for high earners, these people are watching as the SNP also effectively gives a gift to well-off frequent flyers via the halving of air-passenger duty.

Now, some people who are politically savvy may say that this is just politics, and that of course you place yourself in the middle ground to win an election. Grow up and smell the coffee, they say. Again, that’s politics.

Sorry, but so often during the referendum and general election, the SNP/anti-Union rhetoric was how Labour was basically too frit to raise taxes because it would have cost them in marginal constituencies (the UK equivalent to “swing” states or congressional districts in US politics), where only a small swing is needed to flip a constituency from one party to another. Many such marginal constituencies – usually inhabited by middle class voters not keen on tax increases – happen to be to England. Thus, the implication was that Scots are more amenable to paying higher taxes, and that Labour betrayed working class Scottish voters (who wanted tax increases on upper earners) to chase after middle-to-upper income English voters (who didn't want taxes increased), and this was used to argue for separation and voting for the SNP.

Not only does the SNP admit that the same holds true in Scotland, but Sturgeon herself has said that higher taxation is only possible as part of the same UK tax base to prevent people from shifting money and company headquarters outside of a tax base that benefits Scots and everyone else (and because Scotland has comparatively fewer higher income earners than England). In the face of this, during First Minister’s Question’s last Tuesday, she went so far as to say that increasing the top rate would be “reckless” and “daft.” The First Minister would later say that she would consider the 50% rate during the lifetime of the next parliament, but still cited civil service experts warning her against it - at least initially - during the first year of full income tax devolution.

Again, this article is not arguing the merits of tax policy for one of the issues here is the SNP selling itself as a radical, left wing, redistributing party that did things differently than everyone else, like raising taxes on those who can – at least in theory – afford them. In fact, it has proven not to be that party, and is every bit as cautious as the others, so as to not "scare the horses" (i.e., the middle classes).

The other issue is selling this premise that Scots are vastly to the left of the English (and making this a reason for secession), when again, this is false. If this was the case, the SNP would have no problem raising taxes, but like every political party, it wants power, and rarely do parties win power on the promise of raising anybody’s taxes.

The Labour Party learned this in the 1980’s and 1990’s as it clawed its way back into the British political mainstream and eventually into power in the landslide of 1997, which infamously included the wipeout of all the Scottish Tory MP’s. However, it may be a mistake to conclude that anti-Tory sentiment alone was responsible for this, whether in a Scottish or UK political context. If this had been the case, then Labour should have won the 1992 general election and the Tories should have by all rights been wiped out in Scotland following the Poll Tax debacle of 1989-90.

Alongside the anti-Tory sentiment, the strategy of becoming “New Labour” and moving rightward to the center ground under Tony Blair allowed Labour to win in places it had never won before, or in a long time, throughout the United Kingdom, including Scotland, where the party had made itself acceptable to the middle classes, just as they had done in England and Wales. This helped it to win in constituencies that had been sending Conservative MP’s for decades, such as Edinburgh Pentlands, Dumfriesshire, and Eastwood – the safest Tory seat in Scotland which fell to Labour’s Jim Murphy in 1997.

With devolution and the Scottish Parliament, the SNP probably thought they could show up Labour’s progressive and social justice credentials with their “Penny for Scotland” platform to raise the standard rate of income tax by 1% under the power to vary taxes by up to three percent. This was in response to Labour cutting that standard rate by 1% for the UK overall, and SNP looked to cancel this out in Scotland to provide more money for public services. This proved unsuccessful for the SNP’s electoral chances, and the policy was subsequently dropped.

After that, the SNP worked on building its own moderate, centrist, and middle class credentials by painting itself as a party that would govern with modesty and with an eye on being competent – in short, a safe pair of hands that would not rock the boat. In many ways, they were first attracting the people who would have voted Conservative, but did not, perhaps because of the toxicity of the Conservative label in Scotland.

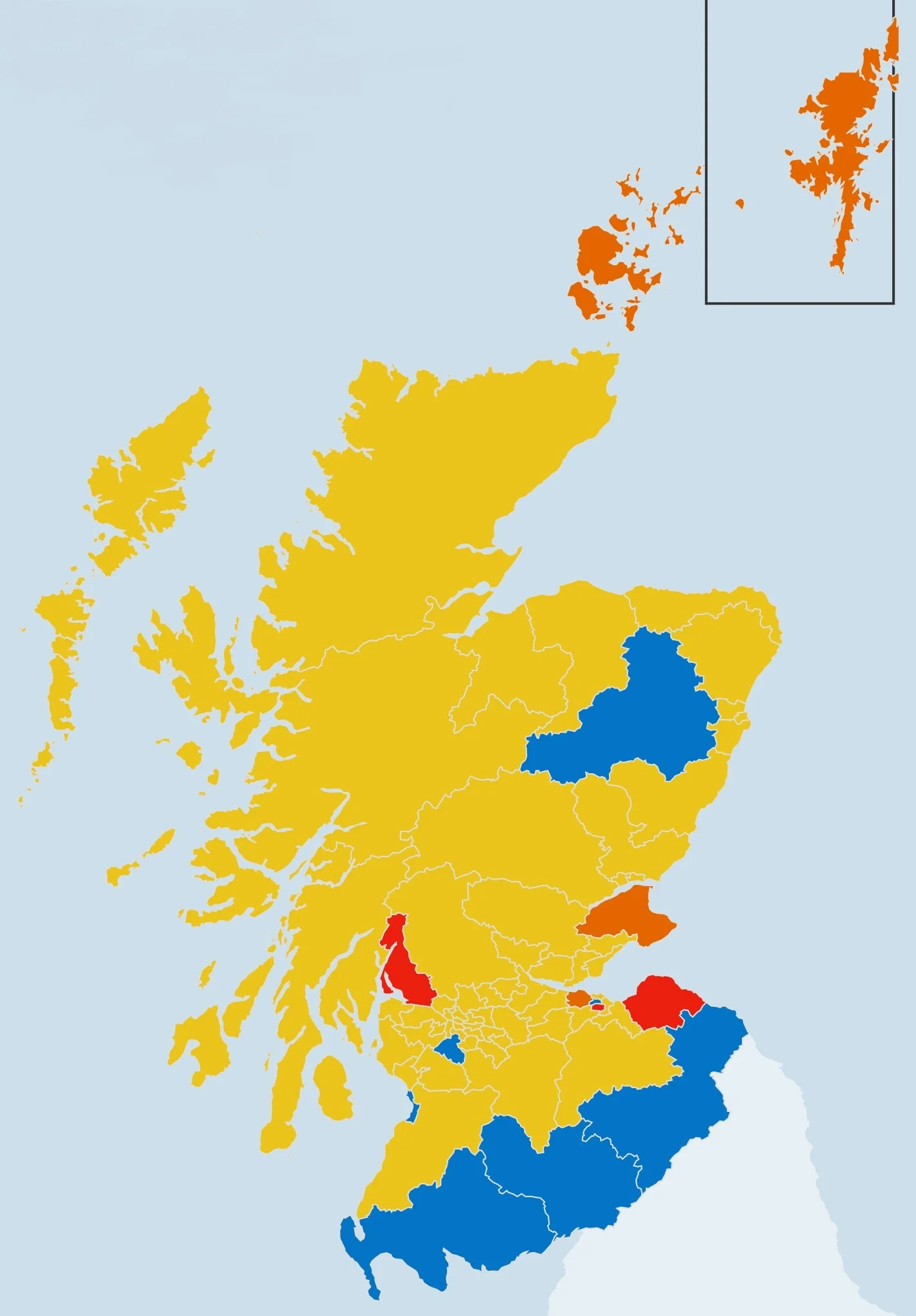

From here, the SNP made itself increasingly presentable to the middle classes and were able to dislodge the Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition administration from power by winning one seat more than Labour in 2007. Then the SNP went after the Labour and Liberal Democrat vote by painting itself as the true defender of the social democratic order in Scotland, while Labour and the LibDems were in cahoots with the Tories in attempting to dismantle it by following an “austerity agenda” of low taxes and spending cuts. This worked to pave the way for the SNP majority government in the election of 2011, the ability to get 45% of Scots to vote for separation in 2014, and the near sweep of the Scottish seats in the House of Commons last year.

Journalist David Torrance's reaction to those expressing surprise that the SNP is not as left-wing as advertised.

All the while, the party’s use of left wing rhetoric to help whip up discontent with Labour and drive up the pro-independence vote betrayed its true nature – like all parties – in being cautious with the reins of power, and even willing to pursue policies that don’t fit the typical mold of socialism or social democracy, such as dropping corporate tax by three points in order to attract business and investment and incentivize job creation.

Such a policy is usually seen as a good thing by economic conservatives, but as an unnecessary giveaway to CEO’s and wealthy shareholders by those who see higher taxation as indicative of a fairer society. That policy was abandoned, but now with Nicola Sturgeon going against a rise in the top rate of income – at least for now – there are questions about her and her party’s credentials as a social democratic party. Writers Iain Macwhirter and Kevin McKenna have written about this phenomenon of the SNP apparently not even willing to use the powers it now has or the huge electoral mandate it is destined to have this May – largely on the back of people who became politically engaged during and following the referendum.

SNP members and supporters have already taken to social media to express their discontent with the party on taxes and other policies where they believed it would at least try to take risks to create the fairer society the SNP has been talking about. Some have even announced their withdrawal from the party – wondering what point there is in voting for the SNP if it’s just going to be another party of the establishment. Indeed, what is the point of secession when the risks of raising taxes will be just as great if not greater, and if an independent Scotland more-or-less follows the economic policies of the rest of the UK?

That being said, there is little to suggest that the SNP will do nothing other than win an unprecedented third term in power in May. If it does so ruling out a tax increase or no firm commitment to raise taxes, it will partly be a manifestation of that fact that there are people out there who may like the idea of higher taxes, but when it comes to actually doing the deed of voting for higher taxes (especially when it effects them), they tend to go with the party that either pledges to lower taxes or keep them the same. A Survation poll in February showed that most Scots wanted either a decrease or no change in the basic rate of income tax, and even a combined plurality of 47% wanted a decrease or no change in the top tax, as opposed to 38% who wanted to see an increase.

Survation online poll - February 25th-29th.

Labour or the Liberal Democrats may not win this election (or even gain any seats) on a pledge to raise people’s taxes, but this may show that when it comes to paying for higher taxes, Scotland is not different than England, and the SNP will likely act in a pragmatic fashion that may well disappoint its new voters.

Brian Wilson probably said it best in the Scotsman this past December:

Nobody ever lost money by reassuring the Scots that we are the most caring, altruistic, welcoming people in the world, uniquely blessed with an egalitarian gene which makes us a’ Jock Tamson’s bairns.

Equally, it is some time since anyone won an election through even the most timorous effort to translate that self-image into votes.