Who's "Anti-Scottish", Now?

/SNP advertisement from the 2007 election.

This week, the SNP unveiled its plans for local government taxation should it win the Scottish parliamentary election in May.

Under the proposed changes, households within the four highest Council Tax bands will have to pay more for the funding of councils; specifically, those living in the average home at the lowest of these bands (Band E) will pay an extra £105 per year, while those living in the highest band (Band H) will be paying extra £517 per year. For everyone else in Scotland – those who live in homes within the lowest bands of A through D – there will be no changes to how much they pay.

The biggest revelation by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon was that the package included the end of the Council Tax freeze in 2017 – ten years after the SNP implemented it when it came to power for the first time. The freeze was conducted under the pretense of helping all taxpayers by providing tax relief and it has been funded by the Scottish Government, which provided the money on the condition that the local councils did not change Council Tax rates (i.e., the “freeze”). However, the initiative has been criticized – including by the SNP government’s own poverty “czar” – for disproportionately benefiting those on higher incomes and living in larger homes at the expense of funding for public services.

Sturgeon has claimed that the move to make those in the higher property bands pay more will raise £100 million for education initiatives, whilst the end of the Council Tax freeze and giving councils the ability to vary it by 3% per year will allow them to raise another £70 million for public services.

In addition, those who are asset-rich but cash-poor – living in higher band homes on low incomes, such as pensioners – will be entitled to an exemption, and there will be relief across all property bands – particularly families with children. The First Minister further claimed that the charges for those in all bands will still be lower than of the freeze were not in place, average rates will remain lower than those in England, and that there were no plans for revaluation of properties, which are still taxed based on valuation from 1994.

In many ways, this seems all well and good – getting rid of the prolonged freeze to give councils more breathing room and making changes to the overall system to make it “fairer”.

However, it amounts to an overall tinkering with the present system, which is something they had criticized doing in years past. In fact, heading into the 2007 Holyrood election, Nicola Sturgeon as deputy leader of the SNP had said: “the Council Tax is unfair and cannot be improved by tinkering around the edges.” She had made this statement following the announcement by the Scottish Tories under then-leader Annabel Goldie that if elected, they would retain the Council Tax system with a discount for pensioners.

To be fair, the Council Tax as been criticized throughout the United Kingdom by people of all persuasions. It was cobbled together by John Major’s government following the disastrous debacle over the Community Charge (aka, Poll Tax) which provoked a campaign of nonpayment, as well as riots and helped to bring down his predecessor, Margaret Thatcher. Council Tax has not generated such feeling as the Poll Tax, but is still considered unfair and regressive in many quarters as a means of funding local government.

However, in responding to the Conservatives’ policy on retaining the Council Tax, Nicola Sturgeon went further in her criticism by calling them “anti-Scottish” for wanting to do so. Specifically, she said: “The anti-Scottish Tories have clearly run out of ideas as this is not the first time they have announced this policy.” Her party campaigned in 2006 and 2007 on a pledge to abolish the “unfair Council Tax” in Scotland and replace it with a “fairer local income tax where over half a million pensioners pay nothing and most will pay significantly less.”

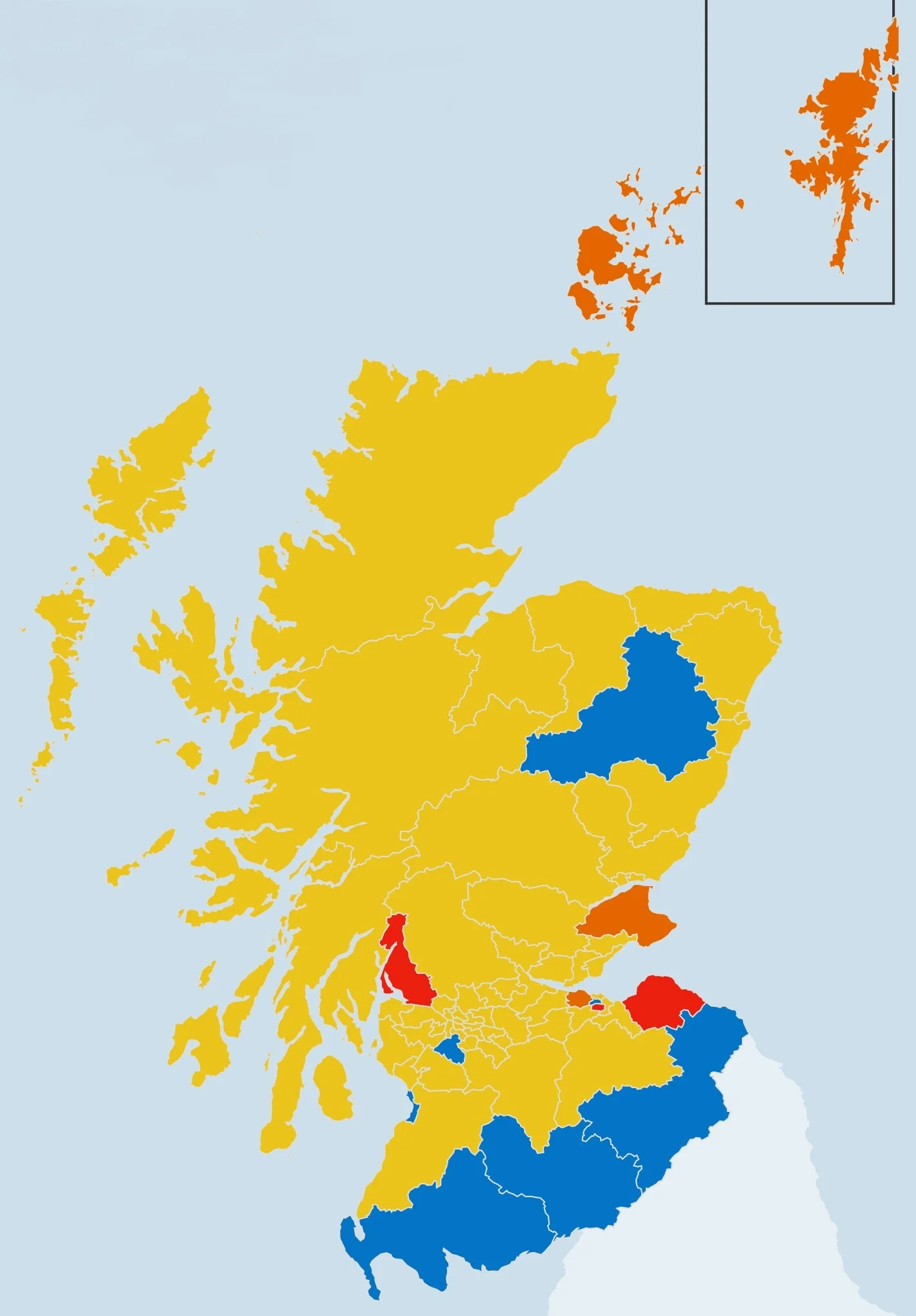

In May 2007, the SNP won the parliamentary election and formed a government for the first time, and they instituted the Council Tax freeze as a precursor to their objective of permanently replacing it.

Once they got to the nuts and bolts of crafting policy however, they quickly realized that a local income tax was insufficient and undesirable; insufficient – because it could not be enough to bear the weight of funding local government, and undesirable – because it would have to be set by Holyrood and thus erode local accountability.

Given these concerns, the SNP went into the 2011 election saying it would: “consult with others to produce a fairer system based on ability to pay to replace the council tax and we will put this to the people at the next election, by which time Scotland will have more powers over income tax.” Following that election, the cross-party Commission on Local Tax Reform was created during the current parliament and presented its recommendations in December – calling for the end of the Council Tax.

In the wake of this, the SNP decided to forgo an all-out replacement of the Council Tax and instead, opted for the position of merely tweaking and reforming the current system.

As Brian Taylor of the BBC noted, it has been a “long, slow retreat” for the SNP on this issue, and having placated the people with the nine year freeze, they now hope that this modest, moderate plan will be enough to satisfy the voters in thinking that they have kept their promise of producing “a fairer system based on ability to pay”, even if they failed to “replace the council tax.”

Possibly the greatest irony of this climb-down from abolition is that the policy decided upon by the SNP shares much similarity with the recommendations offered by the tax commission created by the Conservatives. Tartan Tories, indeed.

However, this may not matter for the election that occurs in two months. Indeed, one of my acquaintances on Twitter, who goes under the name “El Del” (@Del_ivered), believes that the very modesty of the proposed changes only further ensures the SNP’s reelection prospects. Specifically, he notes how the ability of councils to raise tax by 3% may actually be the SNP effectively passing on some of its ability to tax from Holyrood on to those councils, so that councils are left with the decision to raise council taxes for public services, but income taxation in Scotland stays the same as in the rest of the United Kingdom.

This is important, because Labour and the Liberal Democrats have been advocating for increase in income taxes in Scotland in the belief that it may be attractive to some voters who believe that people – especially those of a higher income – ought to pay more for the benefit of public services. Not only does Del contend that they fell into a Nationalist trap, but they were “so hellbent on unleashing their tax missile at the SNP, they were blind to the vital bigger picture: Keeping [the] UK a level playing field and Westminster budgets relevant to Scots.”

In this light, he further asserted that while the SNP does not “care a whit for UK cohesion”, they also did not wish to see talent drain away from Scotland to other parts of the UK due to tax differentials and that “calls for worker solidarity across the UK at the indy referendum were forgotten as [Kezia] Dugdale and [Willie] Rennie were happily prepared to make Scotland the highest-taxed part of Britain.”

Having avoided this and for achieving a “reformed” (i.e., “tinkered”) Council Tax system, Del believes that pointing to broken promises by the SNP on abolishing and replacing it will prove to be ineffective because voters care about the here and now.

However, pointing out this broken promise on Council Tax replacement is necessary when one realizes the circumstances of the election in 2007. To be sure, there were many things going on which help to explain why Labour lost power to the SNP that year, but this was still an election in which the SNP only beat Labour by one seat to form a minority government in Edinburgh. Given how close this election was in some individual constituencies (not to mention the irregularities and various voting/counting/ballot paper issues – possibly most infamously in Cunninghame North) and in the Scotland-wide result, it is possible that the “abolish and replace” promise was probably enough to help the SNP to power for the first time. Looking back, this election proved consequential, for it eventually led to the referendum, further constitutional upheaval, and nine years of SNP rule (with the last five years as a majority government). Without that promise, it is possible that Labour would have held on to power. At the very least, enough votes against the SNP would probably have kept it from attaining power that year, and all things being equal, prevented the madness of past nine years.

Another issue is the fact that Sturgeon called the Conservatives “anti-Scottish” for taking the very position that that her party is now promoting: retaining the Council Tax system with some adjustments. Furthermore, during the 2011 election, senior SNP MSP Humza Yousaf tweeted that Scottish Labour was "betraying Scotland" by not lending its support for "scrapping the unfair Council Tax." Well, what does this make the SNP? As Euan McColm said recently in The Scotsman, "there's something troubling about the othering of politicians by opponents. It speaks of a pettiness that's a world away from the talk of consensus and working together that we so often hear."

For that matter, if certain powers are not to be used because of the resulting disadvantage to Scotland (and the benefit of the rest of the UK), then what is the purpose – the need – for devolution, more powers, the recent struggle over the fiscal framework, or even separation? Indeed, this would seem to take the argument for the Union, as I explained a couple of weeks ago. Again, the SNP may not care about the unity of the UK, but they have paradoxically emerged as a UK unity party.

Then again, it probably comes down to a simple fact: nobody likes paying taxes, and when they do pay taxes, they’d rather not pay any more. Even when they say they believe in higher taxes to fund public services in surveys and polls, so often, they vote according to their pocket books and not their political or social ideals – in other words, they usually vote according to their own economic self-interest.

This may prove difficult to understand for people such as Lesley Riddoch, who seem to be wondering why the SNP is timid in its ambitions for local taxation. Why, they ask, is the SNP passing up an opportunity to really shake up the system of local taxation and come up with something new, innovative, and radical? The reason why is that Scotland is not as radical as she thinks or hopes, and the SNP knows this. Like most political parties, they don’t want to “scare the horses” (i.e., the middle classes, who tend to decide elections) so that they can stay in power. Indeed, some of those within Middle Scotland (a close cousin of Middle England) who benefitted from the freeze may well be shocked at having to pay more after nine years of frozen rates.

In addition, as Brian Taylor pointed out, the SNP knows that any major change in local government taxation will be first such change since the advent of the Poll Tax, and we all know where that went.

This brings up the important fact that there are no plans for a revaluation of properties, which means that Council Tax bills will be based on valuations from over 20 years ago – and that current property values are not accounted for and some people are effectively paying at a discounted rate. This sounds similar to what happened in the 1980’s when the Tories kept putting off what they knew would be unpopular revaluations and increases in the old domestic rates, until they couldn’t any longer (especially in Scotland) and decided to solve this problem by introducing…the Poll Tax.

It is perhaps possible that similar conditions are being produced which will eventually force the SNP to move further on local taxation than it has thus far. For the moment however, they seem content with more-or-less adopting the position on local taxation taken by Tories in that consequential election of 2007. Who’s “anti-Scottish”, now?